Raising Their Voices for LIBERTY

August 18th, 2020, marked the centennial of the Nineteenth Amendment, which prohibited the federal government and state legislatures from denying any citizen the right to vote based on sex. It was a hard-fought victory for women’s rights activists, but, as we see everywhere from Hong Kong to New York City, true equality still waits beyond our grasp.

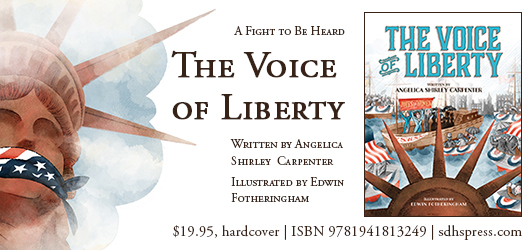

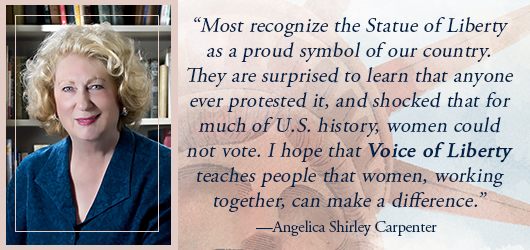

Angelica Carpenter’s picture book, The Voice of Liberty, pays homage to the ideological ancestors of those now marching in the streets for justice through the story of a protest staged by women’s rights activists at the unveiling of the Statue of Liberty. With women barred from the official unveiling ceremony, a group of activists rented a cattle barge to join a celebratory flotilla around the island, waiting for their moment to remind the world that Liberty’s lamp did not yet shine on everyone.

We caught up with Angelica for an interview about this timely title. We hope you find her answers as thought provoking as we did.

Being that 2020 marks the hundred-year anniversary of women winning the right to vote, the fight for women’s suffrage has been on the minds of many this year, but what inspired you to write about this event in particular?

In 2018 the South Dakota Historical Society Press published my young adult biography Born Criminal: Matilda Joslyn Gage, Radical Suffragist. Matilda was a writer, historian, organizer, and leader in the early women’s rights movement, working closely for decades with Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton. She excelled at staging demonstrations like the 1886 protest of the Statue of Liberty depicted in my new picture book, The Voice of Liberty. Why protest that beautiful statue? Because Matilda and her friend Lillie Devereux Blake, both leaders in the New York State Woman Suffrage Association, thought women had no liberty, not even the right to vote, in the United States.

In Born Criminal, I told how Lillie, as president of the New York organization, applied to speak at the Statue’s dedication ceremony on behalf of women, but was turned down. Then she applied to sail in the naval parade and, surprisingly, that request was granted. But the only boat the women could find to rent was a smelly, double-decker cattle barge. The captain promised to have it scoured but he did not keep his word. Even after I finished Born Criminal, that cattle barge stuck in my mind and my nose. I kept seeing those well-dressed women, some overcome by the stench, refusing to board. Eventually I decided that the story would make a good picture book and this idea grew into The Voice of Liberty. I was thrilled when my publisher got the famous illustrator Edwin Fotheringham to do the pictures.

Though a hundred years is a long time, it is apparent there is still a long way to go for obtaining equal rights for women in the United States. Perhaps the most obvious example, as you mention in your book, is the delayed ratification of the Equal Rights Amendment, which was passed in 1972 but has yet to become federal law. What lessons do you think can be taken from the fight for women’s suffrage as we look to the battles still ahead?

Sadly, I think we still face decades of struggle. Longer, even, when you think of oppressed women in other countries, and I believe that we must think globally. The main lesson is to keep fighting, to go step by step, doing whatever we can as individuals or by forming groups to advance the cause. In their book Half the Sky: Turning Oppression into Opportunity for Women Worldwide Nicholas Kristof and Sheryl WuDunn say, “In the nineteenth century, the central moral charge was slavery. In the twentieth century, it was the battle against totalitarianism. We believe that in this century the paramount moral challenge will be the struggle for gender equality in the developing world.” I agree with them about that noble cause. It provides a call to women’s rights advocates. Currently people are protesting and demonstrating worldwide, demanding equal rights for all, just as the activists in The Voice of Liberty did.

What is something you have learned in your research on women’s suffrage that you wish was covered more?

People of color. White privilege. Lesbianism. Separation of church and state. Atheism. Birth control and abortion. Sex slavery. Child abuse. These are big issues, but sometimes it’s the gaps that are most frustrating when I write. Any history includes gaps. I think of myself as a literary detective, but I don’t always solve the mystery. How many slaves did Matilda Joslyn Gage help when her house was a stop on the Underground Railroad? Where did she hide them? What libraries did she use in her research for the many books and articles she wrote? Readers ask me these questions, but I don’t know the answers and I don’t have any way to find out. Some things should be covered less: Anthony, Stanton, and Amelia Bloomer. Bloomer was a newspaper editor who popularized the fashion also known as “reform dress,” so the style took on her name. Americans are fascinated by the idea of bloomers, so she gets a lot of attention, but actually it was Elizabeth Smith Miller who introduced the style to white women in the 1850s.

Similarly, the conversation on women’s suffrage often centers around the same handful of names—Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, most notably—and leaves the contributions of other activists unacknowledged. Is there an unsung activist you’ve encountered in your research who you think deserves a larger share of the spotlight?

Matilda Joslyn Gage was written out of history by her so-called friends, Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton. Matilda’s friend Lillie Devereux Blake and her rival Lucy Stone both thought the same thing happened to them. Matilda believed in equal rights for all but Anthony and Stanton, and the mainstream women’s movement overall, were racist and classist. As we celebrate the centennial of the Nineteenth Amendment, the United States is making a belated but worthy effort to look beyond Anthony and Stanton for women’s rights leaders of color. So Sojourner Truth was added to Anthony and Stanton in the new Central Park statue honoring women’s suffrage. Newspapers and books have sought out overlooked stories to tell and own voices authors to write these. Building a wider, more inclusive historical base enhances the current movement, too.

Do you have any other irons in the fire at the moment you can talk to us about?

Writing two books about Matilda Joslyn Gage has turned me toward other women’s rights leaders as future subjects. I have always written about authors, liking them because they write about themselves, and I expect to continue doing so in this new direction. My agent is trying to sell two young people’s book proposals, but I’m superstitious about discussing them before I have a contract. If there is any news, I will post it on my website at angelicacarpenter.com.

Danielle Ballantyne