Release of Daniel Clowes's 'Patience' Brings Comics Back into Public Eye

March marked the release of Patience (Fantagraphics), the first all-new graphic novel by Daniel Clowes in more than five years. Clowes has won Eisner and Harvey Awards, a PEN Award, and was nominated for an Academy Award for screenwriting, for his adaptation of Ghost World. It’s safe to say that there will be more awards coming for Patience, which pushes Clowes’s body of work into new directions while exhibiting the hallmark care and attention to detail of his other books. But it could be broad appeal, rather than a shelf of awards, that makes Patience a notable book for both readers of graphic novels and those unfamiliar with the form.

Eric Reynolds, Clowes’s editor on the project, recently recalled his first look at Patience: “I first saw the book in the fall of 2014, visiting Dan on a trip to the Bay Area. He had very purposefully not let anyone look at it until it was completely drawn. He finished sometime around November 2014 and I was able to spend some time looking over all of the original art, which was a singular thrill.”

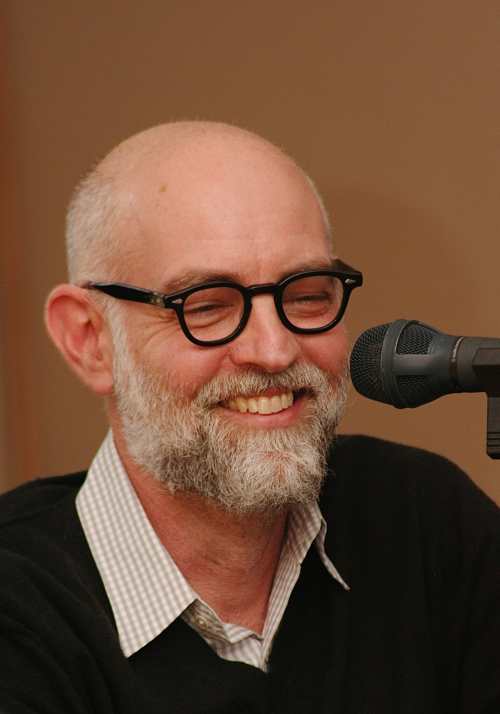

Daniel Clowes

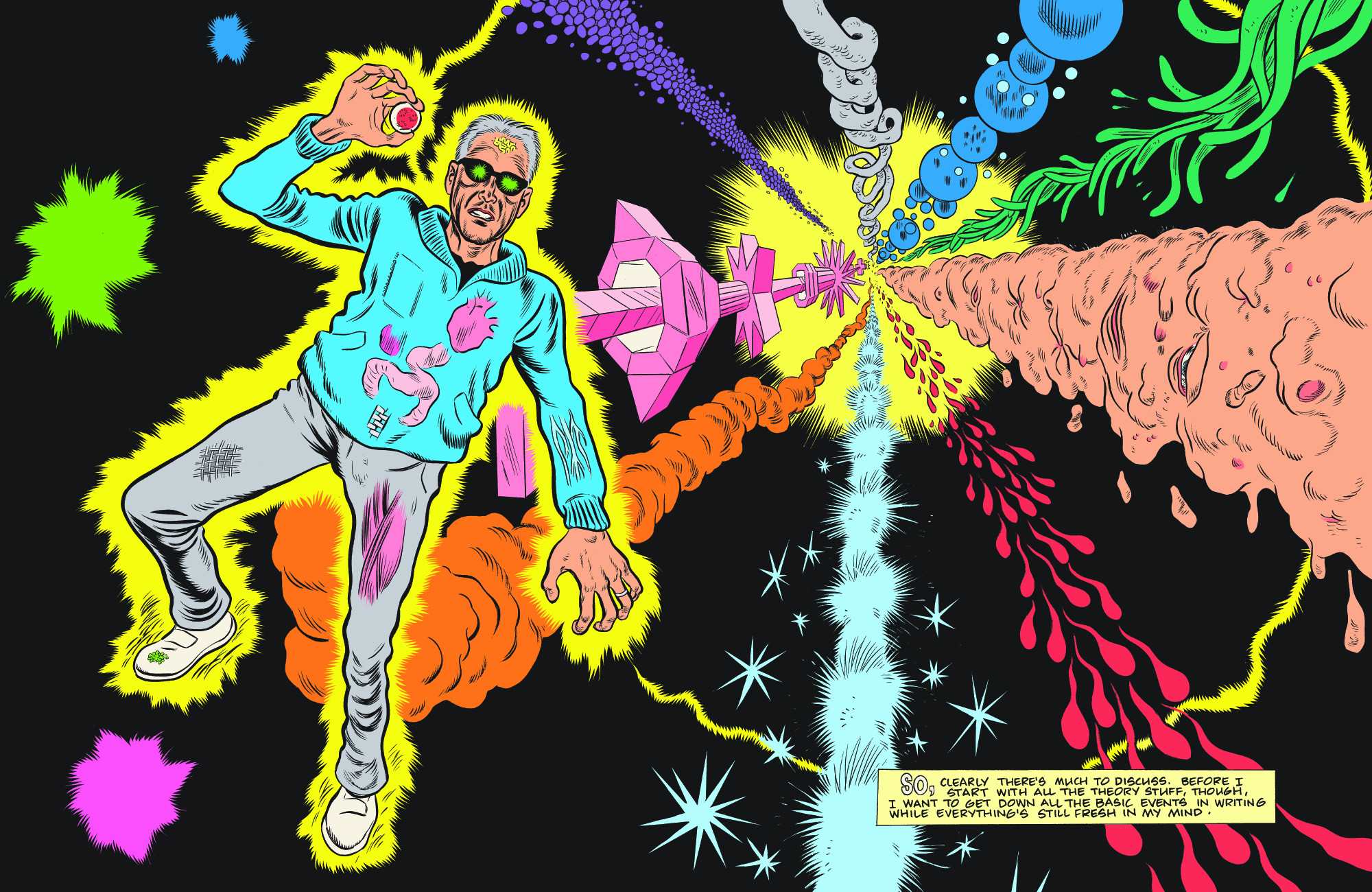

Patience is the name of the female lead in the story, but it’s also an apropos title; the main character, Jack, utilizes a time machine but is limited by his supply of “juice” for it, and thus spends much of his time … waiting. It’s a book about purpose and dedication, a sci-fi head trip that’s grounded in people, not technology. There are some impressive pages depicting time travel that incorporate a psychedelic look; what’s perhaps less eye-catching but more critical to the book’s overall success are the choices of layout, details of personality and clothing, and even the distinctly Clowesian technique of overlapping or blocking word balloons, often to the point of obscuring the text within. This, too, brings the story and characters closer to home, imparting a cinéma vérité feel to a format where, in traditional word balloon layouts, everyone always waits until someone’s finished before talking themselves.

Reynolds was quick to point out that aside from a few small catches in proofreading, the finished product is “pretty much exactly what came in from Dan. [..] The best cartoonists can put on paper exactly what they see in their heads, and I think Dan is in greater control of his craft than just about anyone I can think of.”

Forging Own Path

There was a time, not so long ago, when attention for “serious” graphic novels seemed to require that they recount some autobiographical or near-autobiographical experience (the more harrowing, the better). Patience is a welcome reminder that graphic novels are at their best when they forge their own path, borrowing a sci-fi concept if need be (without apologizing for it), while simultaneously surpassing any rigid preconceptions that a “time machine story” might dredge up.

“So where does Patience fit in with Clowes’s other output? Patience is both perfectly complementary to the rest of his body of work, yet also completely singular, if that makes sense,” Reynolds said. “It reads like a Clowes book in the best possible way, yet comes as a complete surprise.”

Clowes has developed enough of a reputation for excellence that most of his readers won’t care much about the book’s genre classification, they’ll buy it on his name alone. And while it’s great that an accomplished creator is enjoying the rewards of his efforts, there’s also another consideration.

Going Mainstream

It’s tough to imagine many graphic novels getting more mainstream attention (and deservedly so) than Patience. Clowes is one of a handful of graphic novelists mentioned in noncomics media coverage. The Ghost World film garnered a lot of attention when it came out, and Clowes’s graphic novel Wilson is being developed as a film, too, with Woody Harrelson in the lead role. It would be surprising if Patience didn’t one day see a film adaptation as well.

If you’re reading this, then it’s very possible (maybe even probable) that you’re already familiar with the myriad capabilities of pictorial storytelling, which Scott McCloud, author of Understanding Comics, described as offering “range and versatility with all the potential imagery of film and painting plus the intimacy of the written word.” But you might also be, or at least know, a person who doesn’t read comics, who wouldn’t even know where to begin, if so moved. These are the people that a major offering by a comparatively famous graphic novelist, if properly publicized, might draw into the comic book fold.

Maybe one day, there won’t be such a stark division between comics readers and those who generally find their entertainment and edification elsewhere, and the idea of a book “bridge” between the two groups will seem quaint or misguided. But I’d argue that we’re not at that point yet. Until we are, we can, at least, all have Patience.

Peter Dabbene wrote the graphic novels Ark and Robin Hood. He is a reviewer for Foreword Reviews, and his poetry and stories have been published in many literary journals, collected in the photo book Optimism, and in the story collection Glossolalia. His latest books are Spamming the Spammers and More Spamming the Spammers.

Peter Dabbene