Reviewer Ashley Holstrom Interviews Wyatt Williams, Author of Springer Mountain: Meditations on Killing and Eating

Today’s interview topic got us thinking: does the Republican-Democrat political divide also extend to eating meat?

According to a recent YouGov survey—after correcting for variables like age, education, sex, ethnicity, household income, whether respondents live in a city or rural area, own any pets, and how often they go to church—Democrats are nearly twice as likely as Republicans to say they’re trying to limit their meat consumption.

Alas, that stat isn’t surprising—but does it teach us anything or is it just more telltale of how polarized we are as a nation? More telltale, we think.

Like most authors, when Wyatt Williams set out to write Springer Mountain: Meditations on Killing and Eating, he had some questions: “Why do we kill animals and why do we eat them? Is it right or wrong? What constitutes ethical behavior in a godless world?”

But to his credit, Williams says, “I wasn’t foolish enough to believe that I would find any answers.” Instead, he decided to seek out the how and not the why: “How do we kill animals? How do we eat them? How do we behave? Those were questions with answers.”

Alright, let’s get around to the task at hand. After reading her wonderful starred review of Springer Mountain in the September/October issue of Foreword Reviews, we asked Ashley Holstrom to help us better understand this remarkable book (and man).

The book goes far beyond the initial catalyst of the imaginary Springer Mountain, into the history of meat-eating and vegetarianism in humans. Why did you choose that to be the title of the book?

I tend to think we get to the big questions in life by walking through small, specific doors. A decade ago, when I stumbled onto a deceptive marketing scheme—a major poultry company marketing themselves as a local family farm called Springer Mountain just north of Atlanta—I had no clue it would lead me to years of research that would consume my life, working on farms, slaughtering animals, and considering those larger questions you mention. I just thought I was an investigative reporter trying to figure out the story I was working on.

Over the years, Springer Mountain took on a lot of different meanings for me in that process, some I mention in the book, some I don’t. Here’s one I left out: If you hike the Appalachian Trail, Springer Mountain is either the beginning of the journey or the end, depending on where you start. I’d like to think this book could be read differently in that way, that it depends in part on where you begin with it.

Anyway, Springer Mountain is just the little door that led me into this book.

The vignette format with historical accounts and anecdotes side-by-side works really well here. How did you land on that organizational choice?

Thanks for saying that. It took a long time for me to figure out how to write this. I wrote a few different versions over the years, the last one I threw out at the end of 2019. I rewrote the whole thing in 2020. It wasn’t until I gave up on polemic writing—on the idea of forcing some kind of argument onto the book that I didn’t really believe—that I was able to write something that felt honest and clear to me.

The vignettes came about because I realized I simply wanted to tell my own story of trying to work out these questions. Once I realized my motivation here was psychological, not informational, it became much more clear what could be written and what could be cut. I wanted to show my work in that way: the trouble of reconciling the past with the present, the problem of putting facts and information in context with personal experience. To whatever extent that the vignettes work—and I’m glad of course that you think they do—I think it’s because I’m not manipulating them in service of a prescriptive argument. I’m simply trying to show the way I’ve thought through these questions about killing and eating animals, my own ambivalence about ever answering them satisfactorily for myself, my own attempts at coming to some kind of peace about that.

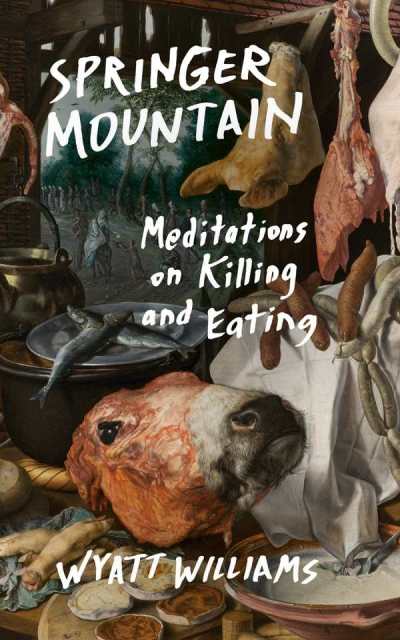

Some of the art and photos of slaughtered animals and factory farming equipment throughout Springer Mountain are gruesome; what was the thought process in including them in the book?

There’s a line from James Agee’s introduction to Let Us Now Praise Famous Men that I quote in the book: “If I could do it, I’d do no writing at all here. It would be photographs; the rest would be fragments of cloth, bits of cotton, lumps of earth, records of speech, pieces of wood and iron, phials of odors, plates of food and of excrement.”

The thing about immersive journalism, the kind of research I did for this book, is that I’m trying to have these physical experiences and come back and translate them to the page for a reader to experience. On the one hand, that’s a good thing, in part because most people don’t have to wander around in pastures trying to figure out what they think about cows, in part because having those sorts of experiences (at least for me) can take a long time to process. I really believe in the power of writing to make our lives fuller and richer in that way, to give us experiences we might not otherwise have. On the other hand, I know that I’m always failing those experiences in my attempts to write them, no matter my insistence on fidelity to the facts, my note taking and record keeping. There are limits to language; there are places in our lives where words fail, no matter how hard we try to make them work. I think that’s what Agee was getting at. The pictures are just that—acknowledgements that there is more here than what I can write.

Has the work of Springer Mountain changed your personal eating habits?

Well, I think the simplest way of answering that question is that somewhere along the line while working on this project, I lost my appetite and quit my gig as a restaurant critic. I didn’t want to relate to the world in that way. I guess I could present that to you as a moral choice but I really don’t think it was. I simply couldn’t enjoy the work anymore.

That said, I get this question a lot, and so I’ll be clear because I think some people are curious: I still eat meat. I don’t hunt much anymore, but mostly because I have bad eyes and don’t think I should be in charge of aiming anything. Nor do I think I’m the sort of person anyone should turn to for dietary advice.

My partner and I used to keep chickens in our backyard in Atlanta. Her daughter sold the extra eggs to our neighbors. Every once in a while I’d slaughter one for stew. It’s good practice, sharing food with your neighbors. I miss that routine, but we’ve moved around quite a bit since then. We just moved to Iowa City and there’s a farmer here who sells corn, cantaloupes, and tomatoes in the parking lot of the Ace Hardware near our house. When I get done answering these questions, I’m going to make dinner from what I bought from him this morning. That’s a fine way to eat, I think.

Ashley Holstrom