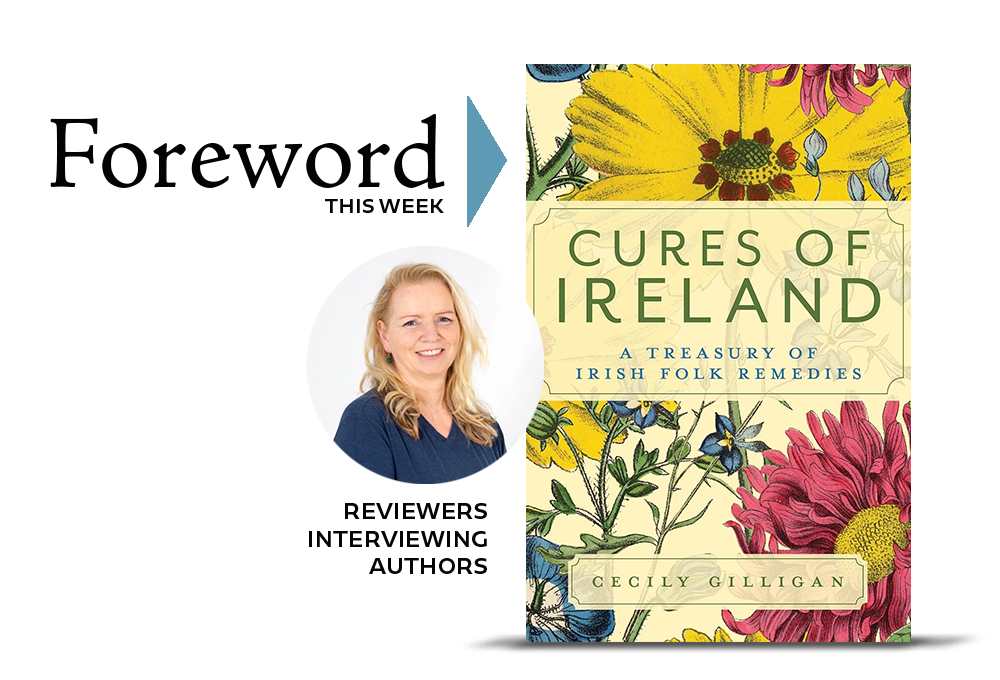

Reviewer Bella Moses Interviews Cecily Gilligan, Author of Cures of Ireland: A Treasury of Irish Folk Remedies

“Most of the traditional cures that are to be found in contemporary Ireland can be regarded as faith cures. … Those who seek a cure generally have faith in it and believe it will work, and this conviction is seen as contributing to the success of the cure. … I believe that the saying of prayers, by those receiving and giving cures, can often provide reassurance and hope, and can enhance the healing process.’’ —Cecily Gilligan

These words from Cecily Gilligan’s got us thinking about whether any scientific proof exists showing that faith and positive attitude play a beneficial role in healing from illness?

In a word, no. Even as many studies do seem to suggest that medical outcomes favor patients with strong religious beliefs and optimistic mindsets, science can’t yet explain why. And that lack of evidence is a source of frustration to the many people facing life-threatening illnesses who are counseled by family and friends to stay positive and—amazingly—good things will happen. It’s unsettling to the patients because the thought of death terrifies them and the simple act of staying optimistic seems so banal.

Not to mention the ubiquitous “I’m praying for you” greeting cards put in the mail by millions of people who don’t have cancer. When you’re hooked up to a chemotherapy pump and feeling like death warmed over, the idea of a benevolent, cancer-curing God coming to the rescue can be maddening: “if God’s so kind, why did he give me cancer in the first place?”

Our point is not to belittle your desire to show your concern for loved ones and friends who are ill. Rather, it’s to encourage you to avoid a blanket approach and instead, read the patient. Meet them where they are. Yes, write a thoughtful card but skip the cliches. Better yet, pick up the phone and just listen.

Cecily’s Cures of Ireland: A Treasury of Irish Folk Remedies earned a glowing review from Bella Moses in the Gift Ideas feature (PDF here) in Foreword’s March/April issue. For access to all one-hundred reviews in Mar/Apr, you can register for a free digital subscription here.

Your work for this book began nearly forty years ago when you were studying Irish folk medicine as an undergraduate at Cork University. What spurred you to return to this project now and why do you think these traditional practices continue to add meaning and dimension to people’s lives in the present day?

I have retained a lifelong interest in folk medicine; I find it a fascinating subject. It an aspect of Irish life that is rarely discussed. But it is an important tradition that is worthy of documentation and preservation for future generations to benefit from. I have felt a compulsion to pursue my fieldwork, and have enjoyed it very much, meeting many wonderful people along the way.

It is amazing that the old cures have managed to survive despite the modernisation of Ireland and the immense changes that have taken place in our economy, society, culture, and religious expression. The cures live on because they are meeting a human need, more than a physical need, a psychological and a spiritual need too, and healing and good health incorporates these three elements. The cures are part of a wider, more holistic approach to healing, and they have the strength of being deeply rooted in traditional culture.

You have also experienced cures firsthand when you were cured of jaundice and ringworms as a child. Did this experience spur your interest in these practices? How did your personal or community history inform your perspective?

The traditional cures have their roots in the land, and this is where they have survived and thrived for generations. In the Sligo countryside, where I grew up, the cures were part of community life; they were well-known and utilised by many. I had a close relationship with my grandmother; I remember her taking me, a young girl, for a walk through our fields at dusk to the fairy fort. We stopped close to it and listened; we heard the cry of the banshee and saw the shadowy figure of a woman at the edge of the wood. Since then I have loved the stories of Ireland long ago, our folklore and mythology.

The cures are part of an oral tradition; they are not advertised or publicised, and information regarding them is usually passed by word of mouth. Therefore, it took time and perseverance to locate and talk to those making cures. Often, I got into my car and went searching; sometimes phone calls proved helpful to track down a cure. Support from my community was invaluable. Family, friends, neighbours, and work colleagues who were aware of my interest gave names to me. Ultimately, I interviewed more than ninety people, and compiled a list of over three hundred people with cures.

As you mention in the book, people with cures are often hesitant to share the details of these practices with the public. Did this pose a difficulty for you? How did you negotiate the ethical or cultural dimensions of creating a book like this that will presumably be read by a non-Irish audience?

Most of the people I approached were willing to speak to me, to share their experiences and thoughts on their cure. However, many of them did not want to draw attention to themselves or their cure. I have respected people’s wishes and not used their names, and have generalised where they live. Lots of cures contain an element of secrecy, how the cure is made, the prayers that are said, the herbs that are used. Many believed that it would be detrimental to their cure to reveal the secret. For some the secrecy surrounding their cure is seen as a way of ensuring its protection and survival; they will not tell anyone how they make their cure until they are ready to pass it on. I always respected people’s secrets, and was nevertheless able to gain a broad understanding of my subject.

My book is written from an Irish perspective, but on a topic of global interest—ways to maintain good health. The World Health Organization’s Traditional Medicines Strategy states that for many people today, “Across the world, traditional medicine is either the mainstay of health care delivery or serves as a complement to it.” And a recent United Nations’ Global Assessment Report on Biodiversity, highlighted that “an estimated 4 billion people rely primarily on natural medicines for their health care and some 70 per cent of drugs used for cancer are natural or are synthetic products inspired by nature.” Well-known medicines which are of plant origin include quinine (from cinchona bark), aspirin (from willow bark), morphine (from opium poppy), and digitalis (from foxglove). There is much we can learn from the natural world globally.

How did the form of this book come about? You were working with such a mass of information, cataloging hundreds of cures and rituals. How did you organize and categorize this wealth of information? How do you imagine a reader moving through or using the book?

My interviews took the form of a qualitative study, a series of questions which I felt were the most important and relevant to the subject. The answers supplied in these conversations have formed the core of my book and determined the chapter contents. I interviewed women and men, of all ages, with a wide variety of cures, both faith-based and herbal. These people have cures which are alive and well; some make their cure several times a week, others a few times each year. Additionally, I documented a selection of holy wells, pilgrimages, blessed clays, and curing stones. I also included two historical chapters which look at healing in Ireland down through the centuries.

Cures of Ireland is an easy book to read. It is written with a light touch, accessible to all, and can be dipped in and out of. Karen Vaughan’s beautiful illustrations compliment the text. There is an expansive bibliography which I hope will be a helpful resource for others interested in herbalism, folklore, and history. I have documented one little-known aspect of Irish life in the 21st century. I am hopeful that my work will inspire others to make their own explorations into the folklore and folk medicine of their countries.

You describe how the tradition of faith cures in Ireland is supported by a culture of generosity, with healers rarely accepting money in exchange for their services. Given the high and rising cost of medical treatment around the world, this seems to be one thing that makes this tradition distinct. What do you think sustains this culture of compassion and community care?

Yes, generosity is a striking aspect of the cure tradition of Ireland. I found that people with cures are extremely generous with their time and energy, and in their willingness to help others, to ease them of their pain and problems. Most people accept gifts in thanks for their cures, some accept money, but they will often give this to charity. The tradition of exchange remains very strong; this is the belief that something, no matter how little (often food or drinks), should be given in exchange for a cure.

Ireland is a small country, with a population of just over seven million on our island (the Republic and Northern Ireland). There are lots of connections between people, and a strong sense of place exists: community remains important. When someone gets a cure, the atmosphere is usually relaxed and friendly. Those with cures often make them in their homes and they are welcoming to the people, locals and strangers, who come looking for their help. A significant human interaction occurs; an individual gives their personal cure to another individual. In many instances the sick person is made the centre of attention, their concerns are listened to and compassion is shown for their plight. As with most things Irish, there is generally a lengthy conversation attached to the procedure and sometimes a cup of tea!

You also mention how traditional cures often rely on the physiological or spiritual will of the person being healed for success. What role do elements like belief, emotion, and mental health play in these traditions? For the people practicing and receiving cures, what is the relationship between folk healing and religious practice?

Do people have to believe in your cure for it to work, do they have to have faith in the cure? This was a question I always asked those I interviewed and the answer was overwhelmingly yes. I clarified “faith” as meaning faith in the cure, rather than religious faith; for some people these two faiths are entwined. Those who seek a cure generally have faith in it and believe it will work, and this conviction is seen as contributing to the success of the cure.

I think that an awareness of past successes of a cure most likely offers a degree of hope to the person receiving it. This awareness is created by those who recommend the cure. Therefore, an expectation that the cure will work can exist prior to its administration, a positive expectation which is conducive to healing. Also, when someone needs a cure, a process must be gone through to get it. I believe that the process involved in getting a cure can contribute to a positive outcome; making a conscious decision to try a cure, locating, pursuing, and committing to it, is proactive and empowering, and could help stimulate the person’s innate healing ability.

Most of the traditional cures that are to be found in contemporary Ireland can be regarded as faith cures. They partially or totally consist of prayers and their success is generally attributed to God. Many Irish people still hold strong religious beliefs; Catholicism was an integral part of their upbringing and it has been a core institution of Irish society for decades. At times of difficulty and crisis in people’s lives, such as when they are sick, people turn or return to their religion for support. I believe that the saying of prayers, by those receiving and giving cures, can often provide reassurance and hope, and can enhance the healing process. Focus on the physical ailment may be lessened, and the psychological and spiritual aspects of the individual may be activated to contribute towards their cure.

What were a few of the most memorable cures you learned about when completing your research for this book?

I was intrigued by the cure for heart problems which was made by an elderly man. The person coming for the cure had to bring pinhead oatmeal with them. He filled a small glass to the top with the oatmeal and then covered it with a handkerchief. He turned the glass upside down and moved it anti-clockwise around the person, pressing it to their clothed body at five different locations close to the heart. As he performed this ritual, he slowly recited a blessing: this procedure was repeated three times. More prayers were said, and he then removed the cloth from the glass. If there was a problem with the person’s heart some of the oatmeal would have disappeared. The person receiving the cure had to take home the oatmeal that remained in the glass, and cook and eat it as soon as possible. They returned twice more to have the ritual repeated, and until the oatmeal in the glass remained unchanged. If there was no indentation in it, this was taken as a sign that the heart had healed.

I spoke to a young woman who was a high-school teacher, and a seventh daughter with a cure for ringworm. Her parents knew of the tradition of the seventh daughter having this cure and they tested her with a worm when she was a baby. They had placed a worm in her hand and it died within a few minutes. If she puts a worm in her hand today the same thing will happen. She told me that her cure involved a simple procedure: she put her right hand on the ringworm for a short while, then her left hand on it. If the affected area was very large, she moved both hands over it at the same time. Occasionally, she felt a burning sensation in the centre of her hand, especially if the ringworm had not been there long. Those who wanted the cure visited her on three separate days, and tradition stipulated that these were Mondays and Thursdays. She said that she had started making the cure as a child with the help of her parents and that it was an ever-present part of their family life. They were and are all involved in her cure, “without them I wouldn’t have the cure … without my sisters I wouldn’t be a seventh sister.”

Bella Moses