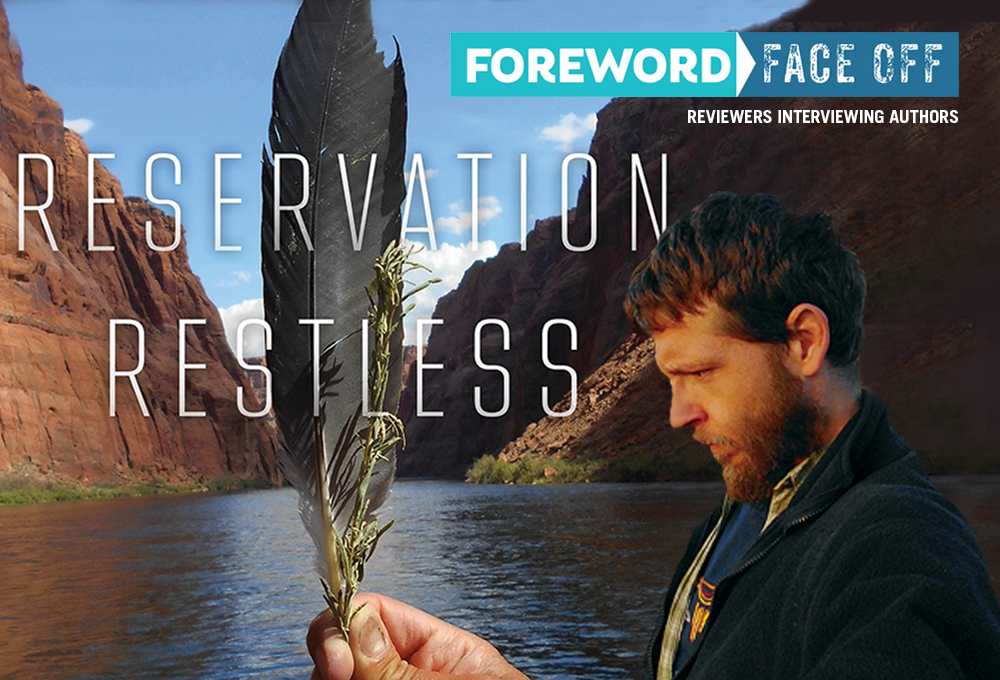

Reviewer Camille-Yvette Welsch Interviews Jim Kristofic, Author of Reservation Restless

Every so often, at just the time in your life when you are receptive, someone steps forward to teach you something. It may be a podcast, a passage in a book, or a chance conversation in the post office, but the universe suddenly reveals a secret about itself and—aha—everything shifts a bit. You are more you. Your place in all of this is that much clearer.

This week, we’re lucky to spend time with a desert sage. One of those people who can summarize a conversation about the differences between women and men by saying, “It comes back to the mythological understanding of things: a woman is made by nature, and a man is initiated by society. A woman is a force of life and a man is the servant of life.”

It takes a lot of reading, thinking, observing (and perhaps some desert botanicals, for all we know) to see things so clearly, and we’d be wise just to hear the man out. The man is Jim Kristofic, the author of several books including his newly released memoir, Reservation Restless. In her review for Foreword’s March/April issue, Camille-Yvette Welsch writes that in addressing “the fraught history between white and Indigenous people, his own personal stories, and the geological features that are particular to Arizona and New Mexico, Kristofic illustrates how places, stories, and the right audience can make a man.”

We fancied the idea of gathering an audience for a conversation between Camille-Yvette and Jim, and the University of New Mexico Press assisted in making it happen.

CY, take it from here.

You grew up on the reservation and spent quite a lot of time in the Southwest though you are not Native. Many authors struggle to write about cultures they were not born into, yet you write quite a lot about Native peoples and customs. What do you do to ensure that your writing feels authentic and respectful?

It all comes back to that sage writing advice: write what you know. Most of what we know and remember is by the attachments of love and pain. It is in the deep emotions where our identities are woven. And from that weave, we return love. I grew up on the Navajo reservation, in Ganado, Arizona. My stepfather is Navajo. My brother and sister are Navajo. I herded sheep as a kid. I helped raise lambs. I rode horses and raised horses. I have helped with ceremonies and attended ceremonies. If I walk around in my hometown, the elder women refer to me as “Sha yazh,” as their son. Me being Anglo has nothing to do with it. It is the shared experience. The shared love of the land and the people. The heart. And a heart doesn’t know about race.

So, most of what I write comes from learned experience and struggle of living on the Navajo Nation. The only conscious effort I might put into the writing is to make sure I don’t reveal certain sacred details too much, as to take away their sacredness. If any readers are curious about this, it is all told in my previous book, Navajos Wear Nikes: A Reservation Life.

Continuity is a major theme that runs through the book, from the land and its stories to Lyle, the teacher with whom you shared such a close relationship. How do you view this book in terms of continuity with your other work?

It’s really all part of one book. It’s all part of a history of my time, as I have experienced it. This book is mostly a continuation of the episodic essays laid out in Navajos Wear Nikes. The experience of being a national park ranger that I tell in the book also ties in with the research I was performing to write the award-winning history book Medicine Women: The Story of the First Native American Nursing School (UNM Press, 2019). Medicine Women tells the story of a group of defiant missionaries and doctors who rebelled against the racism of their day and established a school on the Navajo Reservation to educate Native women (from Alaska to Arkansas) to be nurses in the modern world. The book also tells those nurses’ stories as they moved through the education system. And it tells the stories of local Navajo people who found a way to meet America on their own terms.

In moving through the landscape, you read the clues to see who and what had been here before from animals to people. You call it the beginning of narrative intelligence in humans. Can you explain that further particularly as it impacted you as a writer?

That particular detail tells its own story about the spirit of curiosity. You see the land laid out before you. But you don’t know much about it. You have your fantasies about the land. You have your analogies. But they are not the deep knowledge of people who’ve lived with it for centuries. And I don’t just mean “humans” when I say “people.” You get into the depths of knowledge and you learn that kangaroo rats are a people. Coyotes are a type of people. Eagles are a people. They have their own nations living alongside you. They have their own customs. You watch them. You learn things. You learn that we’re not the only thing going on around here.

So it’s a mystery in plain sight. And you get your whole life to try to understand it. But one life is not enough. You learn the truth of Charles Bowden’s four rules that he articulated in his book Inferno, about the Sonoran desert and all deserts:

You are in the right place.

You do not belong here.

Deal with this fact.

Time’s up.

Danger is an inherent part of the landscape in the Southwest as you describe it. If anything, that seems to intensify your love for it, to recall the awesome and the sublime from the eighteenth century way of seeing the world. How does that fit into your view of this space and your passion to protect it?

It all goes back to the title of that Neko Case album: The Harder Things Get, The Harder I Fight. The Harder I Fight, The More I Love You. I could say that about the Southwest. It is a place where you have to rely on the gods. There is such vast distance. Such precious little water. You must live with the permission of the ground. Or you have to import everything on chassis of steel and tires of rubber on ribbons of fragile asphalt (which is mostly how people live in the Southwest). The ground preserves itself by its own scarcity and honesty. I belong to some organizations that help steward the environment. But for protecting the land, the most powerful thing I can offer is restraint. My own restraint. When I see a place that could be a lion den, I acknowledge it from a distance. I do not disturb it. I do not leave my scent. I respect their territory. I know what plants do and what plants need to be left alone.

Lyle Parsons, your beloved teacher and friend, creates the book’s through-line. At what point did you realize that and how did you come to realize it?

That idea came very early as I wrote the essays. It is a through-line in the book because the book reflects my lived experience. Lyle Parsons is a through-line in my life. We are connected by love. Love is eternal, beyond time. I debated whether I would write the experiences Lyle and I shared, but I was forced to do it. In all those experiences, his presence was there. I carried him as a ghost. This book was meant to honor him. Through this act, he could become an ancestor. A ghost haunts you. An ancestor blesses. You fear a ghost. You worship an ancestor. It is better to keep our loved ones as ancestors. In this sense, the book became a ritual act.

The book posits a couple of ways of being a man—being responsible for someone else’s life, being acquainted with life, being acquainted with death, trusting your own restlessness. How do these ideas come together for you by the end of writing the book?

We have a culture that doesn’t know how to initiate men very well. Many Americans become confused with how they should properly regard what a “man” is and how they ought to behave. It is a time of great confusion. When you ask people if they want to be in the presence of a “powerful man,” they are not sure if you’re talking about a mostly honest man who commands a room with the integrity of his authority (a Fred Rogers or a Martin Luther King Jr.) or a man with power by dishonest means (a Harvey Weinstein or a George W. Bush).

Women are told to be “strong” and “independent.” And this is a good thing. I grew up with a single mother, who was very independent and very strong. And she and I talk on the phone once a week and make each other laugh all the time. But I make a joke to women friends of mine that I’m going to start wearing a T-shirt that says “Strong, Independent Man.” They giggle at the idea, but I also see confusion in their eyes. They almost don’t know what that means or how that should look.

When my grade school teachers asked me what I wanted to be when I grew up, I would tell them a knight of the Round Table or a forest ranger. I’m trying to find that middle way between the two. But my car, my watch (I don’t wear one), my clothing, my shoes, my appearance: none of these have anything to do with how I regard myself. For me, it is about the acquisition of Prowess, about what I know how to do. And then I have to lie as little as possible in order to get those things. If I have to lie and deceive people overwhelmingly to acquire that Prowess, it’s probably no good for my society and needs to be abandoned. I suppose it comes back to the mythological understanding of things: a woman is made by nature, and a man is initiated by society. A woman is a force of life and a man is the servant of life.

But what happens when a man lives in a society that he no longer trusts? That man needs to get busy building a better society. My next book is about just that. It’s titled House Gods: Sustainable Buildings and Their Renegade Builders. It’s a book about sustainable building and sustainable builders in northern New Mexico and my journey to find them and learn from them. It’s a quest story. Adobe mud and mayhem. Shamans and stray dogs. Solar panels and tragedy.

Camille-Yvette Welsch