Reviewer Carolina Ciucci Interviews Alice Vernon, Author of Night Terrors: Troubled Sleep and the Stories We Tell about It

We are mysterious creatures, to others and ourselves. How to explain the creative brainstorms, harebrained schemes, and shudder-causing evil thoughts that suddenly appear in our normally quite sane brains? Why did evolution provide us with consciousness? And, pray tell, WTF are dreams?

We’re waiting … your guess is as good as anyone else’s.

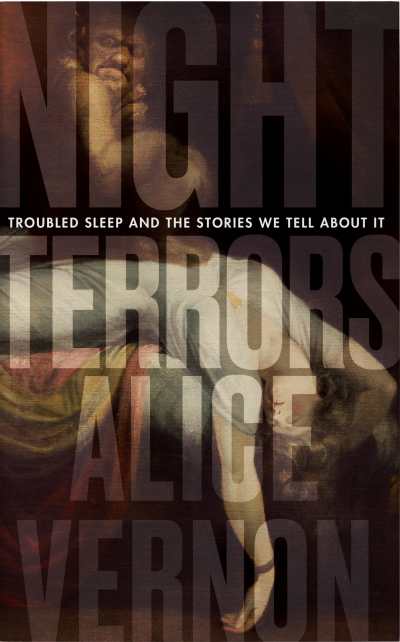

This week, we’re here with Alice Vernon, a woman long fascinated by what happens to our brains during sleep. Taking that interest one step further led Alice to begin research for her new book, Night Terrors, and that deep dive uncovered centuries worth of literature and analysis, some of it mind boggling.

We didn’t hesitate to set up the following reviewer-author interview once we read Carolina Ciucci’s review of Night Terrors in Foreword’s November/December issue. If you have strange things happen on the pillow at night, Alice can offer some reassurance. Enjoy!

Night Terrors is not so much about sleep as it is about the stories we tell about it. Would you say this perspective was influenced by your background as a creative writing lecturer? If so, how?

Yes, definitely! My main research interest involves looking at medical anecdotes and case studies to see how we write and talk about our experiences of health and illness. In terms of sleep, though, it is so subjective and strange that we have to package it into a story that makes sense, as difficult as that can sometimes be. What I was looking for in particular was how we’ve imagined and explained some of these phenomena throughout history, but I also wanted to encourage people to tell their own stories of troubled sleep.

Is there any way, besides talking more openly about our experiences, that people can contribute to ending the stigma surrounding sleep disorders?

I think reading about them will certainly help. Before I started to conduct research for the book, I had so many misconceptions of my own—I had no idea that when I saw spiders all over my bed, for example, it was something called a hypnopompic hallucination. The more we learn about and understand what is really happening when we experience these strange sleep states, the less weird or embarrassed we’ll feel for having them in the first place.

You explain that some parasomnias (such as sleepwalking and lucid dreaming) are romanticized, while others (hallucinations, sleep paralysis, night terrors) are more stigmatized. Could you elaborate on this? What do you think fuels this difference?

In terms of sleepwalking, it seemed to be particularly romanticised in the nineteenth century—especially when the sleepwalker was a young woman. The idea of a woman in an eerily calm trance-like state, vulnerable and often dressed in just her nightgown, seemed to be an object of fascination for a lot of medical men who wanted to watch and study her as she walked about in her sleep. Lucid dreaming is romanticised now, I think, because it’s almost like unlocking a hidden part of yourself. I think a lot of the cultural interest in lucid dreaming coincides with the rise of video games—games become more vivid and immersive, but it can never compare to the sheer reality of the experience of living out those game-like situations in a lucid dream.

These disorders only seem to be romanticised when they don’t involve aggression or panic in any way, which is why hallucinations and sleep paralysis have been depicted so differently in culture.

Do you think there’s been a cultural shift in our perception of sleep disorders, since you began exploring representations of them?

I think there has definitely been a revival recently in terms of including parasomnias in psychological horror films. Last Night in Soho (2021) was quite notable in its depiction of nightmares and sleep paralysis (and triggered a particularly bad night for me!). Equally, though, I do see people dealing with their experiences through memes and internet humour—reacting to a picture of a haunted-looking Furby and saying that it’s their sleep paralysis demon, for example. Lucid dreaming and its therapeutic and creative possibilities seems to claim the biggest cultural interest at the moment, though.

You draw up analysis and inferences from a multiplicity of sources: visual arts, literature, even newspapers and individual anecdotes. How did you go about collecting all of these into a cohesive whole?

I love diving into archives and finding things I wasn’t expecting. Sometimes I get so involved in exploring collections and gathering bits of cool stuff that I forget I actually need to write something with it! I usually start quite broadly with research, and that points me down various avenues and helps me to make connections in terms of a chapter’s structure. Working along a timeline helps, too, but I’m always happy to change my plans once I’ve found something particularly fascinating! The dreams of the British public collected in World War II was something I stumbled across while down a research rabbit hole, and it’s one of my favourite sources in the book.

I was intrigued by the potential of lucid dreaming to treat PTSD. Do you think it could also help other mental illnesses, such as depression or OCD?

At the moment, lucid dreaming can be used to help with nightmares associated with PTSD in that the phenomena can essentially “rewrite” the course of recurring, traumatic dreams. If other mental illnesses such as depression or OCD cause nightmares (and indeed, sometimes the medication for these conditions can affect a person’s dreams) then learning to lucid dream could help any symptoms manifesting through sleep.

Where do you see the study of parasomnias going in the near future?

In my immediate future, I’m really hoping that my book gets people talking about their experiences of troubled sleep. I’ve already done a couple of events, and it has been wonderful to hear people come up and tell me about the things they’ve also suffered with at night. More broadly, though, I think there will be much more research undertaken in terms of lucid dreaming and the ways it could benefit people’s mental health. In fiction, I think parasomnias will always be a trope of the horror genre, but I also think we’ll start to see some of these “spooky” conditions appear in literary fiction, affecting the lives of everyday people who aren’t being chased by monsters or ghosts!

Carolina Ciucci