Reviewer Claire Rudy Foster Quizzes Sam Hooker, Author of The Winter Riddle

At some point during the next couple weeks of holiday cheer, stop yourself mid-mistletoeing to remember that the end-of-year/Christmas celebrations are, well, contrived. Yes, they’re based in historical truth—but in reality it’s a bunch of myths and legends gone wildly, preposterously off track.

Don’t worry, we’re not gettin’ all Scroogey on you, as much as we’re relishing the idea that Santa, tinseled trees, caroling, candles, gift giving, and even stars in the east and three wise men are based in honest-to-goodness genuine tradition, but that time and nog and commercialism did what they do best: make a jolly ol’ mess of it.

And let’s not forget how The Nutcracker, Snow White, A Christmas Carol and other wintry tales canoodled their way into our holiday subconscious. To be sure, the holiday season is nothing if not a dreamy memory theater of Yuletide fantasy.

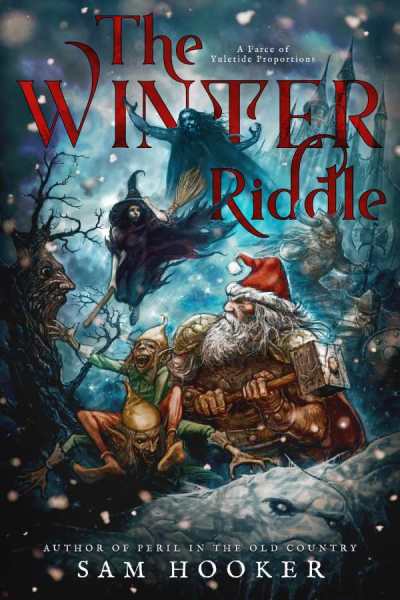

This week, we’re excited to hear from a modern-day fairytaler, Sam Hooker. In his newly released The Winter Riddle, he assembles a maniacal cast of supernatural characters from the world’s panoply of winter-solstice/end-of-year/religion-inspired celebrations. But his White Witch, Loki, elves, druids, necromancers, wintry wizards, and other North Pole inhabitants are decidedly vicious, for the most part. That, and Santa used to have a bloodthirsty habit of chopping up goblins.

Claire Foster raved about the book in her review for Foreword Reviews, so we connected her with Sam via his publisher, Black Spot Books. Here’s your chance to peek into one of contemporary fiction’s most dark and delightful brains.

Speculative fiction seems increasingly like “predictive” fiction. From climate change to corrupt leadership, nightmares or fantasies that we relegated to science fiction have become daily news. Do you consider your novels to be escapist? Or is your fiction based on real-world events?

The best fiction is rooted in the truth, though some roots are deeper than others. People like Tom Clancy write ancient sequoias with roots so deep that readers must occasionally remind themselves they’re reading fiction. They’re the sorts of books that leave one trembling for the fates of nations.

I, on the other hand, write dandelions with roots just deep enough to keep their fluffy little heads from tumbling away in the breeze. I go to great lengths to ensure that any truth that sneaks into my work is absolutely slathered in farce. I do consider my work escapist, which is hard to defend when bold-faced truths roam freely across the manuscript.

The Winter Riddle is superb satire, effortlessly mixing yuletide myths and legends. Which holiday tradition did you most enjoy playing with in this novel, and why?

The best part of the winter holidays is that so many cultures do one around the same time. The Winter Riddle is rife with cultural influences from the Vikings to Wicca, all of which contributed to our modern celebrations. It’s the amalgamation that makes the winter holidays what they are.

I did very little research for this book. I know that’s a terribly unscholarly admission, to say nothing of the unfulfilled travel expenses that I could have written off; however, I think it’s important to acknowledge that I’ve paid very tongue-in-cheek homage to certain cultures from our real world, with intent to neither glorify nor vilify anyone. I truly hope that no one but me takes this farce seriously.

Your work often focuses on the adventures of hapless, unlikely heroes. Peril in the Old Country, in particular, is a hilarious fish-out-of-water story. What appeals to you about characters of this type?

Writing about proper heroes is easy: “A burly piles of muscles straps an ancient magic sword to his hip and charges off to battle the evil wossname. It’s a hard fight, but he emerge victorious in the end, much to the swooning of his voluptuous love interest.”

Writing humor is hard enough without serious heroes getting in the way. Whether my heroes are competent like Volgha, or hapless like Sloot, their reluctance to have anything to do with heroics is a wellspring of comedy.

Each of your novels I’ve read has an ambitious scope: I would call them absurdist epics, as they sprawl beyond the page and create fully realized, fantastic landscapes. This is impressive—considering how excellent your characters and hilarious dialog are—you don’t lean too heavily on those elements. One thing I really enjoy is the way you use landscape, treating it as more than just a swamp for your characters to stumble through. What are your feelings on world-building? When you’re writing, do you envision the landscape first, or let the plot guide you?

I’m quoting you on “absurdist epics.” Time to upgrade the leather patches on the elbows of my jacket.

Anyone who’s been to New York knows that a place is as much a creature as those who dwell within it. You can describe a city, but it’s nearly impossible to properly encapsulate its character with words alone. I can tell you about the particular smell of steam rising from the subway while you’re walking past a street meat cart, or the particular pang of regret that one feels when compelled to touch the handrail on the way down into the subway, which is probably more old chewing gum than painted steel; but if you’ve never experienced it for yourself, no description of mine, no matter how detailed, will ever do it the injustice it deserves.

It is a writer’s challenge to breathe life into a place without the benefit of its existence. The trick, paradoxically, is to provide only as much detail as necessary, and let the reader’s imagination fill in the blanks. We rely on shared truths and universal experience to do a lot of the work for us. If I were to fill dozens of pages with specific details about a place, my readers might feel required to keep up with every bit of it. There might be a test later. On the other hand, if I impart just enough to show the soul of the place, the reader’s mind will naturally give it far more life than I could have done with thirty paragraphs.

Movie studios have CGI, but writers have something infinitely more wondrous: the minds of our readers. That’s where our worlds are built. The true wonder in our creations is in the collaboration between the minds of the reader and the writer.

When I write, all of the characters emerge and grow together. The world in which they reside comes up with them, because it’s as much a character as any of the talking weirdos I’ve concocted.

What’s next for poor Sloot and the Terribly Serious Darkness series?

Soul Remains, the second book of Terribly Serious Darkness, will be on shelves April 23, 2019. It’s already available for preorder. (Nudge, wink, nudge.)

I’m gathering my notes for the third and final book now, and I’m beyond excited to start writing the manuscript. I absolutely love writing Sloot, and I can’t wait to torment him across another few hundred pages. Vladimir Nabokov said, “The writer’s job is to get the main character up a tree, and then once they are up there, throw rocks at them.” I can’t think of a better way to describe my relationship with Sloot. If I’m in a good mood at the end of the third book, he may get something approaching a “happily ever after,” but I can’t promise anything.

Claire Foster