Reviewer Danielle Ballantyne Interviews Jessica Friedmann, Author of Twenty-Two Impressions

“Divination, to me, is an interpretive practice. I don’t believe that you can predict the future with tarot cards, or with any other system, but I do believe that you can make yourself very still and practice a kind of active looking and listening that allows for the symbols of the tarot to emerge in a kind of organic meaning-pattern, one that helps make sense of unspoken or unidentified perceptions.’’ —Jessica Friedmann

Much happens around us that we don’t understand. That fact can either excite us—the world is a far more interesting place than can be imagined—or it can frustrate and cause us to seek out ill-informed explanations.

So, grasshopper, what is your relationship with the big unanswerable questions? How do you handle mystery?

A few intrepid souls—like today’s guest, Jessica Friedmann—approach these questions like this: they quiet their minds, open themselves to every and all possibility, and simply observe. That a deck of tarot cards is also part of their introspective / meditative practice suggests that they have found a helpful tool in better understanding the arcane workings of the universe.

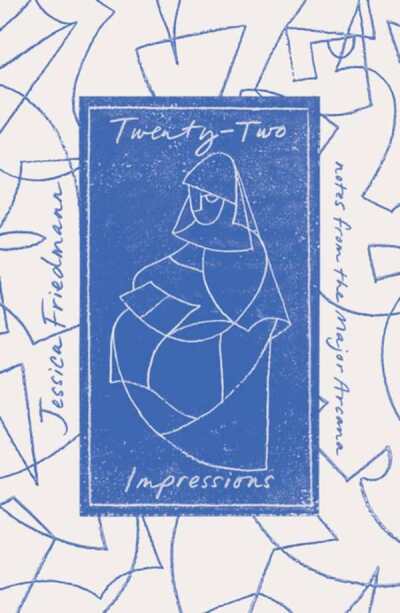

Jessica’s Twenty-Two Impressions is a collection of essays on her relationship with the tarot. In her review for Foreword’s November / December issue, Danielle Ballantyne calls Jessica “an honest narrator who acknowledges and relates to spiritualism skeptics.” In fact, Danielle says, she doesn’t demand that you believe in the tarot, “she only urges openness to the universal lessons and shared human history it represents.”

A kindred spirit, Danielle was excited to pitch a few questions Jessica’s way. We’re certain you will find the conversation eye-opening.

A Self-Help feature (PDF here) figured prominently in that most-recent issue of Foreword, including reviews of stimulating books from Hay House, Hampton Roads, and three other top independent publishers. And remember, a free digital subscription to Foreword is yours for the taking. We’d love to have you subscribe.

You discuss this in the book, of course, but for our readers here, can you tell us a bit about what initially drew you to tarot?

My entry into the world of the tarot came quite late. I’d always been interested in the tarot but felt ambivalent towards what I thought of as *the* tarot, the Rider-Waite-Smith deck, for reasons I couldn’t then articulate.

But about five years ago I was in a post-book slump, and feeling creatively stuck, and a friend offered to do a tarot reading for me. And it was really lovely and intimate, even though I still felt quite disconnected from the cards. This was about the same time that Jessa Crispin’s The Creative Tarot came out, so it felt like a good time to explore the tarot as a writing tool, even if it meant pushing past my own discomfort.

After I bought the book, I poked around the bookshop for a deck, and the only one left in stock was the Tarot de Marseille. And it just immediately felt right, like everything about the tarot had clicked into place. I hadn’t realised how far back the tarot went—it goes back to the 1440s, and probably earlier—and handling a sixteenth-century deck felt really natural and intuitive. I didn’t have to push myself at all.

The more I used them, the more fascinated I became by the idea that this 600-year-old artefact was still so widely available and had survived so much historical turmoil. For a purportedly magical object to survive the Reformation, and the revived Inquisition, and make it through the Enlightenment just seemed so unlikely. It opened up possibilities for a kind of alternate history, one which kept faith with medieval ways of thinking.

Your book uses the twenty-two cards of the Major Arcana as the scaffolding for the essays within. What made you settle on that structure?

The structure of the Tarot de Marseille itself was one of the deciding factors. The twenty-two cards of the Major Arcana were originally a fifth card suit and were used to supplement an ordinary playing deck in the game of trionfi (or “triumphs,” which gives us the name of “trump” cards). So the Pope, for example, would trump a card like the Empress or the Fool.

In the Tarot de Marseille, the Minor Arcana still looks like a standard deck of Italian playing cards, with Italian suits—coppe (cups), denari (coins), spade (swords), and bastoni (clubs)—and court cards. It’s that twenty-two-card fifth suit into which most of the tarot’s symbolism is condensed.

I did originally want to write something more fragmented, to mirror the idea of laying out the cards, and let the reader dip in and out to begin to build up their own narrative. I love books like Tree of Codes which blur the line between literature and visual art, and things like concrete poetry, which encourage alternative forms of reading. But my editors very gently led me towards something more straightforward.

Tarot and many other aspects of occultism have been growing in popularity but are still deeply misunderstood. What would you say is the most common misconception you encounter about tarot?

I was having drinks with a friend the other night and met someone who had been raised in an Evangelical household who grew up believing, and being told, that tarot cards were a tool of the Devil. And I think a lot of people still feel as though alternate or ancestral practices aren’t compatible with religious belief. But charms, amulets, incantations, and divination coexisted with religion in Europe well into the Middle Ages. There doesn’t need to be tension between them.

Divination, to me, is an interpretive practice. I don’t believe that you can predict the future with tarot cards, or with any other system, but I do believe that you can make yourself very still and practice a kind of active looking and listening that allows for the symbols of the tarot to emerge in a kind of organic meaning-pattern, one that helps make sense of unspoken or unidentified perceptions.

You’ve done a lot of research on tarot—both its current incarnation as a tool of spiritualism and its less mystical roots. What was something you learned that surprised you?

I was amazed by the size of the community that has grown up around tarot’s history and by how warm and welcoming it was. It’s a relatively young research field, but old enough to have had two or three generations of writers lay the groundwork for studying the tarot in an engaged and scholarly way, and if you have a question about their work, you can email them.

I’m in a few tarot groups on Facebook that are cross-pollinated by people with really specific interests. There are artists recreating 500-year-old decks using medieval techniques; there are people who research the heraldic shields of the noble houses to see where they might appear on historical cards; there are people tracing the potential trade routes that first took Mamluk cards to Italy. It’s a passion project for so many people.

Apart from just the loveliness of being in a supportive community, it made me less paranoid about my work needing to be comprehensive and more comfortable seeing it as part of a constantly reenergised whole.

Is there a story or anecdote you’d like to share that didn’t make it into the book?

So many things went into and came out of the book that I can barely remember what’s in it! It took me down a lot of rabbit holes. I think there was something about the relationship between tarot and memes, and an extended riff on the use of tarot by children, and maybe a story about Jimmy Page buying Aleister Crowley’s mansion.

At one point, I did have a section which looked at the relationship between Ithell Colquhoun’s Taro as Color, a series of “psycho-morphological” enamel card-sculptures that were exhibited in 1977, and June Leavitt’s theories about German Hasidic theurgy of the Middle Ages and its link to occultist use of the Kabbalah.

Leavitt, in one of her essays, describes a late-thirteenth-century manuscript which instructs that Jews should visualise specific colours when thinking about the sefirot and its “emanations.” Colours, in this manuscript, were explained as the “coverings” of spiritual essences too powerful to encounter directly—an idea which preempts the way that the occultists appropriated colour theory and the sefirot within the Golden Dawn.

The idea of tarot cards emanating pure colour—or auras, or hallucinogenic or spiritually inspired colour fields—was one I felt opened up a lot of possibilities. But there’s a point at which you can become too esoteric, even when writing about esoteric things.

Are you working on anything currently that we can be on the lookout for?

I have a novel on the backburner, but I’ve also just enrolled in a PhD across creative non-fiction and art history, looking at how it might be possible to extend the German iconologist Aby Warburg’s “pathos formula”—a method which organises art history into emotional responses rather than chronologies or movements—into the twenty-first century. Warburg included the Tarot de Marseille in his last major work, the Mnemosyne Atlas, which is what first got me interested in his work.

Twenty-Two Impressions was written on a shoestring between parenting and freelancing and community work, which is how most writers manage to get it done. I was fortunate, I think, that the book lent itself to being written in fragments. But it’s a bit of a dream that weird essays are about to become my job, and I’m looking forward to seeing what I can do over three and a half years of uninterrupted thought.

Danielle Ballantyne