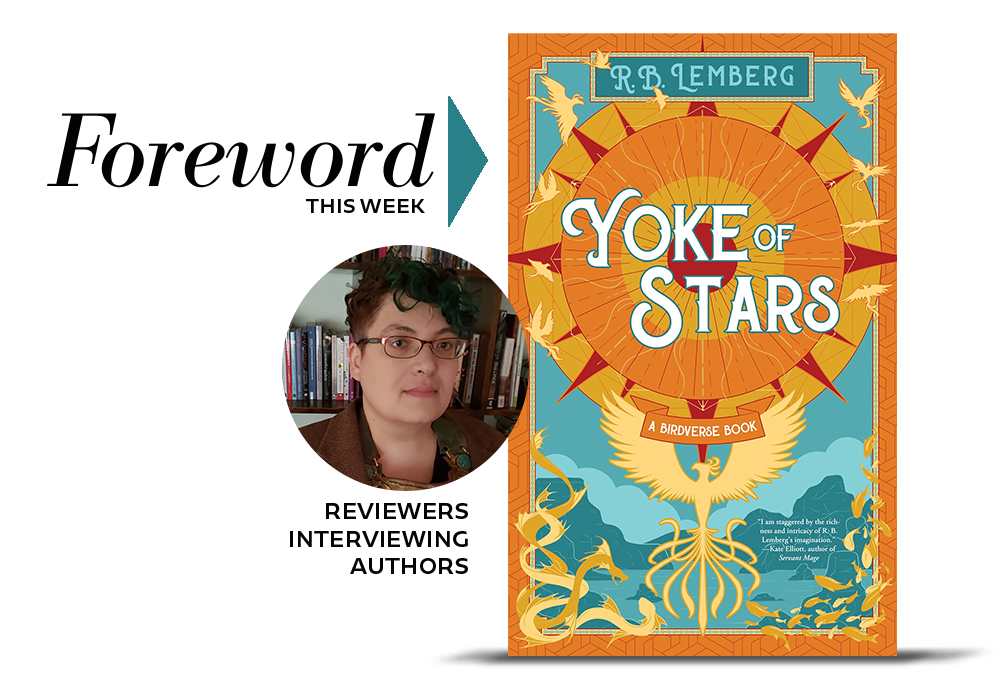

Reviewer Danielle Ballantyne Interviews R. B. Lemberg, Author of Yoke of Stars

“The same story can be told many times, in many ways, by different people across generations. A story can migrate and move around, acquiring new endings and meanings. A story can be told in many languages, a story can be recast in song or art, a story can be forgotten and rediscovered—nothing is fixed and everything is always changing.’’—RB Lemberg

Today, your Foreword This Week assignment is to expand your ideas about imagination. We’d like you to think of it as something more practical and less magical—as if it’s just another routine brain function like tapping a memory or deciding what you want for lunch.

Take a cue from Guy Davenport in his magisterial The Geography of the Imagination: “Imagination is like the drunk who lost his watch and must get drunk again to find it.”

We love that framing because Davenport understood that virtually everything we do could benefit from a little imagination.

So, dust that thing off. Dare to use it, as in the style of Henry Miller calling imagination the “voice of daring … If there is anything godlike about God, it is that. He dared to imagine everything.”

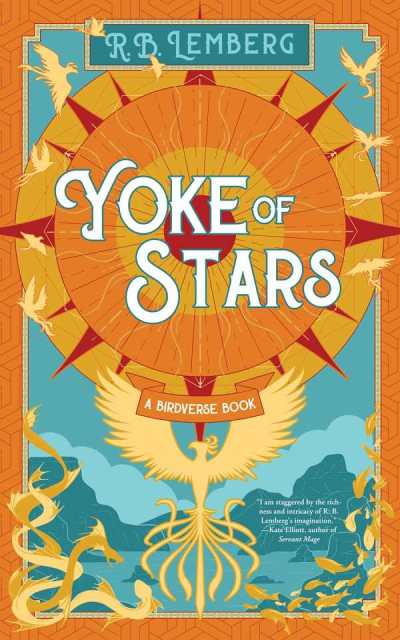

Which brings us to another universe creator, R.B. Lemberg, whose legendary rendering of the Birdverse first enthralled readers of The Four Profound Weaves and now comes back to life in Yoke of Stars, “an unforgettable queer fantasy novel about the power—good and bad—that our words hold,” in the words of Danielle Ballantyne in her review in Foreword’s July/August issue.

Danielle, say hi to R.B.

The Birdverse is such a wholly original fantasy world that it’s difficult to liken it to anything else, real or imagined. How did you come up with such a singular world to construct these stories within?

Thank you so much for this question. I think the Birdverse is such a good map of my brain—I’m constantly thinking about odd things, like the first bird on Earth, or how art was traded in antiquity, or the ancient air trapped in geodes, or the consciousness of stars, or whether grammatical categories define our humanity. I think it always starts with linguistics, with questions about language, and multiple languages coming into contact. I began imagining this world as a graduate student. I was thinking about anthropological linguistics, and all the many problems with it. I had this image of a woman in the wood—she has traveled to meet people in this wood and to study their language, and I knew there were things she was missing, revelations about her own life she was going to discover. The image was very vivid—dappled sunlight through tall trees, a sense of mystery, the movement of wind. I did not know anything else. I think that linguist was Ulín, one of the two protagonists of Yoke of Stars.

All of the novels and stories within the Birdverse relate to one another—and it’s certainly a more satisfying experience to read them all, as I have done—but they can also stand alone. What would you say are the challenges and the delights of writing interconnected but independent books?

I think from the very beginning I wanted the Birdverse to be a tapestry, a world that is woven rather than linear, a reading experience comes together the more it is explored. It is not challenging for me to write this way—this is how my brain works. I experience the world through a sense of multiple existence of things. It’s a concept I learned when I was studying folklore theory—the same story can be told many times, in many ways, by different people across generations. A story can migrate and move around, acquiring new endings and meanings. A story can be told in many languages, a story can be recast in song or art, a story can be forgotten and rediscovered—nothing is fixed and everything is always changing, yet there is a central, vital core at the heart of the telling that is carried through.

I think the way I tell my stories resonates with my readers especially because of the rewarding discovery and re-readability of the work. It is also a challenge—I think our world teaches readers to expect a simple Western style three-act narrative that leads from point A to point B, and we absorb and learn structures from existing storytelling, so there’s an effort and an adventure inherent in reading something different. I am forever grateful to Tachyon and all the other publishers who’ve brought my work out over the years—I think it’s a good thing to have many different types of books in the world. I myself am delighted to read any style, from a cozy English mystery to incredible experimental multilingual poetry. I’m glad it all exists.

Your latest novel, Yoke of Stars, meditates on the beauty of languages not just as tools to create art but as works of art all their own. What drew you to that concept?

I think the concept already emerged in my childhood—multiple languages were spoken in my home (Russian, Yiddish, and Ukrainian; my father also spoke German and learned some Romany in his childhood, and my mother studied French). This was unusual in the context of the Soviet Union, where access to foreign language study was quite limited. I learned early on that showing any knowledge of Yiddish outside of my family home was not a good idea, as Jewishness was suppressed—and yet one of my favorite childhood memories was of very old people visiting my great-grandfather and speaking Yiddish. They were Jewish musicians and actors who used to be employed in the old Jewish theatre in L’viv until it closed. My great-grandfather Motl of blessed memory was a talented violinist who at the end of his life made some extra money by copying music sheets for his old colleagues. I learned a lot of Yiddish by sitting around and listening to them. Later, after my family fled the Soviet Union, I started studying medieval languages on my own. Then I became a linguist. So the ideas expressed in Yoke are the result of my whole life of thinking about languages, migration, bilingualism, and language change.

The novel also addresses bilingualism and translation from a fresh perspective that will certainly be thought-provoking for many readers. What prompted you to explore that?

After the Russian Federation’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, I began doing literary translation of Ukrainian work from Ukrainian (and Russian) into English. I worked with Chytomo magazine to translate poetry, and with some other publishers (like Atthis Arts for their Embroidered Worlds anthology) to translate both poetry and prose. I’ve never before done literary translation, though as a linguist I translate endlessly. The work I’ve done as a literary translator made me think even more deeply about the necessity of translations in a divided world, and the difficult path translators walk, the frequent and frustrating invisibility of a translator’s labor. It made me think even more about ancient translators and multilinguals. It made me think even more about exile, and how self-translation shapes those of us who move between cultures and languages. I think I said what I wanted to say with this book—for now, at least, and I think it would be interesting to those who are curious about translation, migration, and bilingualism from both philosophical and practical standpoints.

There are so many colorful characters across the Birdverse, all with unique voices and personalities. If you had to pick a favorite child (or two, or three; we’re not monsters!) who would it be and why?

Oh, what a conundrum. Many of these characters are so near and dear to me, I am having difficulty picking and choosing. Definitely Ulín, who is my first Birdverse character—she’s never appeared in a published work before, so this is finally her hour. I love Kimi, the nonbinary young person who appears in many of my carpet-weaving stories, including “Grandmother nai-Leylit’s Cloth of Winds.” A tiny spoiler, they have a cameo in Yoke of Stars. I love Semberi, the grumpy ancestral ghost in The Unbalancing. Some of my very favorite characters have not had a chance to appear yet, or appeared only briefly. I hope to get a chance to explore their stories in the future.

Finally, do you have plans to continue your travels within the Birdverse, or is there something else we can expect to see from you soon?

I’m always tinkering with the Birdverse and hope to have more work set in it soon. Right now I am working on a big dark academia project featuring a giantess professor and a postdoctoral student who is a mystic with a violin. Both are migrants in a country where universities are imperiled. I won’t spoil it beyond that. It is set in a world I tentatively call the Ships universe. I have a few stories out set in that world, but nothing big yet.

Thank you so much for a chance to respond to these great questions!

Danielle Ballantyne