Reviewer Danielle Ballantyne Interviews Y.S. Lee, Author of Mrs. Nobody

“It was only when I realized the great joy of Mrs. Nobody and decided to write a wild, playful adventure about the most-fun friend that the narrative really came to life.’’ —Y.S. Lee

What do dogs and cats and little boys and girls have in common: a crazy little thing called play. What’s to be made of that fact—at a time when humans seem to have lost all semblance of their animal origins and dogs and other animals appear so different and distant from us on an intelligence scale? Play, whatever it is, messes with our assumptions.

Psychologists spend whole careers debating the importance of play for children, and veterinarians do the same with animal play—each assuming that play must serve some biological purpose. But play seems to be a thing of its own, unrelated to biology and psychology, from a time before civilization and culture.

Here’s another mindbender: animals have rules when they play: don’t bite too hard, take turns chasing, act very angry. Is play imagination? Is play consciousness?

Play is fun, that we know.

Enjoy today’s conversation about imaginary friends. Mrs. Nobody is a very special book.

The idea of a child needing to stand up to their imaginary friend is such a novel way to teach children about setting boundaries. How did you come up with this accessible way to approach a complex topic like that with children?

Oh, I had so many false starts. Initially, I wrote a story about an excessive and bossy imaginary friend. It included parents and a sibling, and the plot was mostly about negotiating with Mrs. Nobody. The trouble was that it felt very pedestrian.

It was only when I realized the great joy of Mrs. Nobody and decided to write a wild, playful adventure about the most-fun friend that the narrative really came to life. From there, the idea of conflict and boundaries unfurled very organically—if you push boundaries, you need to set some, too.

How did you settle on the name Mrs. Nobody for Alice’s imaginary friend?

Well, the real Mrs. Nobody lived at my house for a couple of very dramatic and stressful (for me!) years. More seriously, though, I love the weirdness of “Mrs. Nobody”—it makes me think of the Emily Dickinson poem “I’m Nobody! Who are you?” And, as a friend pointed out: if you’re nobody, you can be anybody.

Did you have an imaginary friend growing up? Do you recall anything about them?

Not in the classic early-childhood sense. But when I was a bit older—ten ish?—I often carried characters from books with me: often Emily Starr from L.M. Montgomery’s Emily of New Moon trilogy and Meg Murry from Madeleine L’Engle’s Time quintet. They were good company and reflections of my ongoing concerns, so I guess I did.

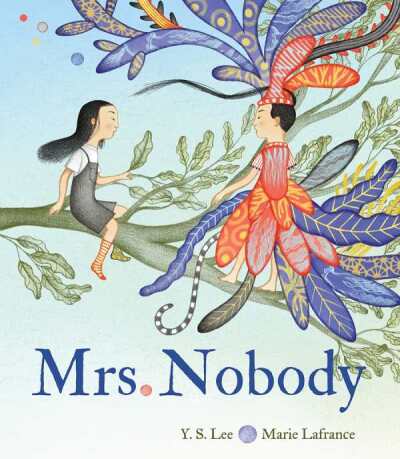

The illustrations are such a potent element of this picture book, tracking Mrs. Nobody’s mercurial moods. Did you work closely with the illustrator to capture these fantastical scenes?

From the very start, I wanted Marie Lafrance to have a huge amount of latitude; this is such a free-spirited story, and I thought too much meticulous detail from me would weigh it down. It was important to me that Mrs. Nobody could change in size—I felt it was an important way to convey the magnitude of Alice’s emotions.

There were a few rounds of back-and-forth, always mediated by our editor, Karen Li, in which I offered notes and Marie responded. I also edited the text a couple of times to reflect Marie’s vision. For example, in the original manuscript when Mrs. Nobody cuts Alice’s hair, I wrote, “All of it!” I had envisioned Alice with a sort of porcupine head. But I was later so charmed by Marie’s rendering that I revised it. I did suggest cutting a big chunk cut out of Alice’s bangs, though—in my experience, children tend to start right at the front!

But Marie really took the story and ran with it. The sentient toys, all the little faces throughout, the dress that turns into a stormy ocean—those are all Marie. I think she’s brilliant.

You’ve authored several books in multiple genres, but this is your first children’s picture book. How was this experience different from your other projects?

I had a huge learning curve in finding the right entry point to the story, as mentioned above. Once that was in place, I also found that picture book texts are more like sonnets, or maybe mosaics—you have a general sense of where you need to go, but there’s so much craft in placing all the individual elements in just the right place. There’s no room for detours or even a single unnecessary word.

Do you have any other projects in the works that we can look forward to in the future?

My agent is shopping around my first middle-grade novel (fingers crossed), I’m at the very beginning of another YA novel, and I’m assembling my first full-length collection of poetry. I’m also tinkering with a couple of other picture book ideas. The problem is never the ideas; it’s making the time to work on them!

Danielle Ballantyne