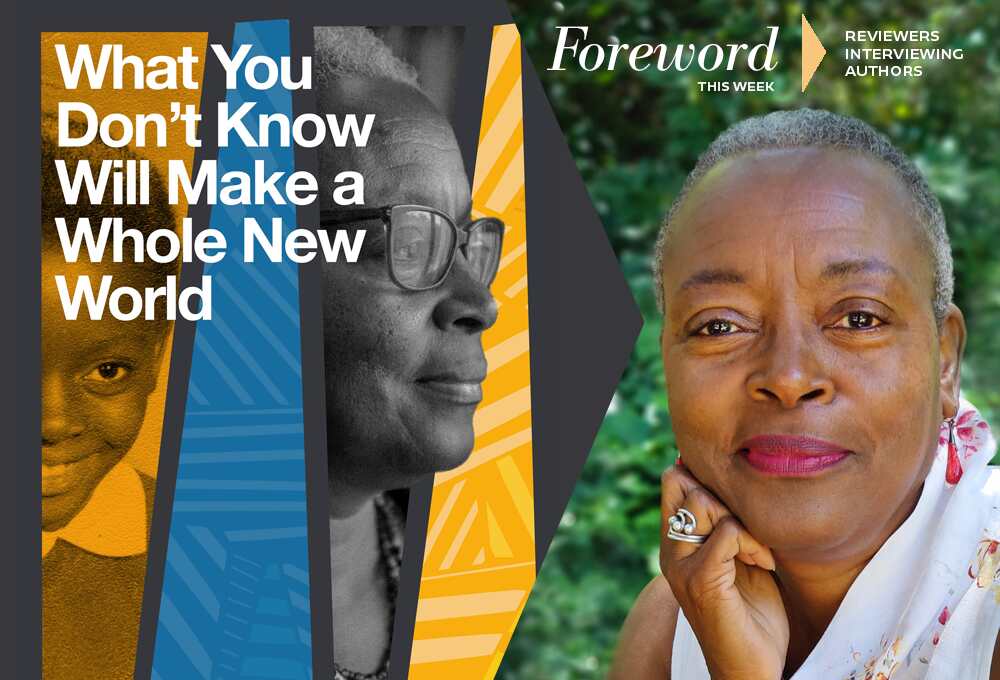

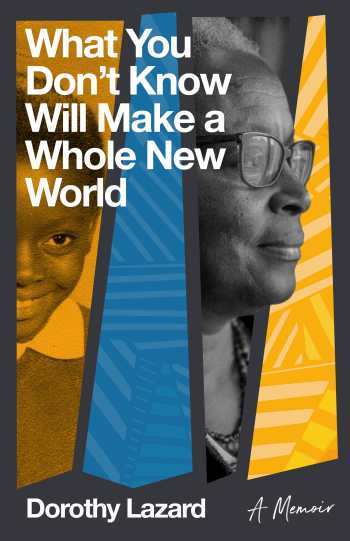

Reviewer Dontaná McPherson-Joseph Interviews Dorothy Lazard, Author of What You Don't Know Will Make a Whole New World

We’re blessed this week to be in the presence of two librarians—one fresh off the release of her

memoir at the end of a storied career, the other some years younger, but also an accomplished writer, as well as a top reviewer for Foreword. They share a deep love for words, history, and the American story in all its trials and triumphs—not to forget the librarian credo to leave the world a better place for future generations.

What You Don’t Know Will Make a Whole New World is what brought them together, writer and reviewer, Dorothy and Dontaná.

Children, gather around to hear some truth.

What was your process like in writing this book? How did you decide what to include and exclude, and where to stop?

I began by writing personal essays about my life, about those influential moments that carved my personality. Every once in a while, I’d write another essay. And over the years, as memories faded, I’d write about other events in my life. As 2018 approached, I decided I wanted to do something to commemorate my 50th anniversary in California. Should I throw a party? Should I do a tour of the state? Finally, I decided that I should write about those first, impressionable years, pull those essays together and write new ones. I focused the memoir on those early years because they marked me more than any other.

Deciding what events to add and what to leave out became easier once I settled on the span of years I wanted to focus on. And, I also wanted to stay true to the genre and true to the child’s perception. Memoir is a collection of memories. It is much more impressionistic than an autobiography which tends to have everything in it, be more chronologically and historically detailed than memoir.

You share some very intense personal experiences, including the deaths of your grandmother and parents. Was there ever a moment during writing where you thought “Oh, I’m not going to share that. That’s too personal?”

There were lots of moments like that. Lots!! And when I was faced with those moments, I had to ask myself, does it advance the story I want to tell? Is it related to something–an event or theme–I’ve already shared? Does it build on a reader’s understanding of me? Why should I add it? What’s my motivation? Some things I didn’t share because I didn’t want to talk about them with the public. It was that simple.

Lately, it has felt like we’re living through the kind of history that will be in books in a few years’ time. Do you remember feeling the same way when you were growing up? If so, what were the events that made you stand up and take notice? You cover some of this in your book, but I’m really curious as to if and how you recognized “Oh, this is an historic moment” during your childhood and adolescence rather than through reflection.

There were many moments in my life that were historic, but when you’re a kid, you don’t know how significant those events are and how they will resonate in the future. For example, no one was calling the Civil Rights Movement the “civil rights movement” when it first began. There are even disagreements on when it began.

As a kid, my historic moments have to do with the challenges my family faced and how they impacted me–my sense of security, of home, where we would live and how. I certainly lived through a lot of major historic moments, but I didn’t gain a full appreciation of their historic significance until I was a teenager. Events like Bobby Kennedy’s assassination mere weeks after Dr. King’s, Watergate, the assassination of our Oakland school superintendent Marcus Foster, the Boston busing conflicts–those stand out in my mind as events that would have impacts on the future.

I think our journeys to librarianship are similar in that most of the librarians we encountered as children were older white women, even at twenty to thirty years apart. What was your catalyst for going into librarianship? Because in your memoir, you end the story just as you are leaping into adulthood by moving away for college, intending to be a journalist.

I went to library school in order to help Black Filmmakers Hall of Fame, the local arts nonprofit that I write about in the book. The staff had aspirations to create a community resource where people could learn about Black participation in the film industry and could learn skills to enter that industry. I thought I could help them sort out all of the materials they had begun to collect (slides, film reels, correspondences, etc.). Little did I know at the time that I’d be in the profession for the next 40 years.

Your grandmother, Mam’Ella, sounds like a formidable woman. She had a wealth of practical knowledge, but was wary of “book-learning” and held on to quite a few superstitions, like thinking someone buried a piece of your mom’s hair, manifesting in her epilepsy. Are there any parts of her that you held on to, any superstitions or beliefs that you still hold dear and have passed on, beyond her words that become your title?

I was always a suspicious child, wary of superstitions, but there are some that I find myself observing like never putting my purse on the floor. Ever! Now, why that would bring bad luck (as Mam’Ella believed), I’ll never know. And I do sometimes quote her whenever there’s thunder and showers on a sunny day: “The devil’s beating his wife.” What does that even mean?!! But I find myself saying it nevertheless.

Your wanderings around your neighborhoods felt very much like a travelogue. Whether you were going to school way outside of your zone or exploring a new neighborhood, you really took us along with you on your journey. When writing your memoir, did you go back to visit any of the places you mentioned if they still exist? If so, what was that experience like?

I did not go back to any of the places. They live pretty sharply in my memory and I wanted to represent the story my memory had to tell.

As I was trying to craft a final question for you on the myriad ways you realized, explored, and fully rooted yourself in your Blackness, particularly during the time now known as the Black Arts Movement, and after, I’m finding it difficult to word. I felt a pang in my soul when you talked about realizing how you would need a public self and private self as a Black child in a white space. I felt your excitement, your confidence, and your sense of belonging grow through middle school and high school.

Perhaps what I’m most curious about is this: Do you feel more rooted in your identity as a Black woman today than you did back then? If so, in what ways and what contributed to that? What words of wisdom do you have for other Black girls and women today?

It’s not that I needed a public self and a private self, that’s just the way society was set up–with the Black community, my Black family influencing me in one way and the white, “mainstream” society expecting me to act in another way. Did I “need” that dichotomy? No. But how can we expect any other result when we have a society that is split along racial lines, where whiteness is paramount, and blackness is demonized?

I feel rooted in my Black identity because of the Black Arts Movement which taught me and my peers that we were beautiful, whole within ourselves, that we were not all the negative labels that society had assigned us. During that time, we had to learn to see ourselves, love ourselves as we were, not as white society said we were. That was liberating to hear and see. There was a lot to unlearn. I see my youth, the period I depict in my book, as a time to retire my sense of self. Too often Black children learn self-hatred before we consciously learn self-love. And that’s a pity.

Dontaná McPherson-Joseph