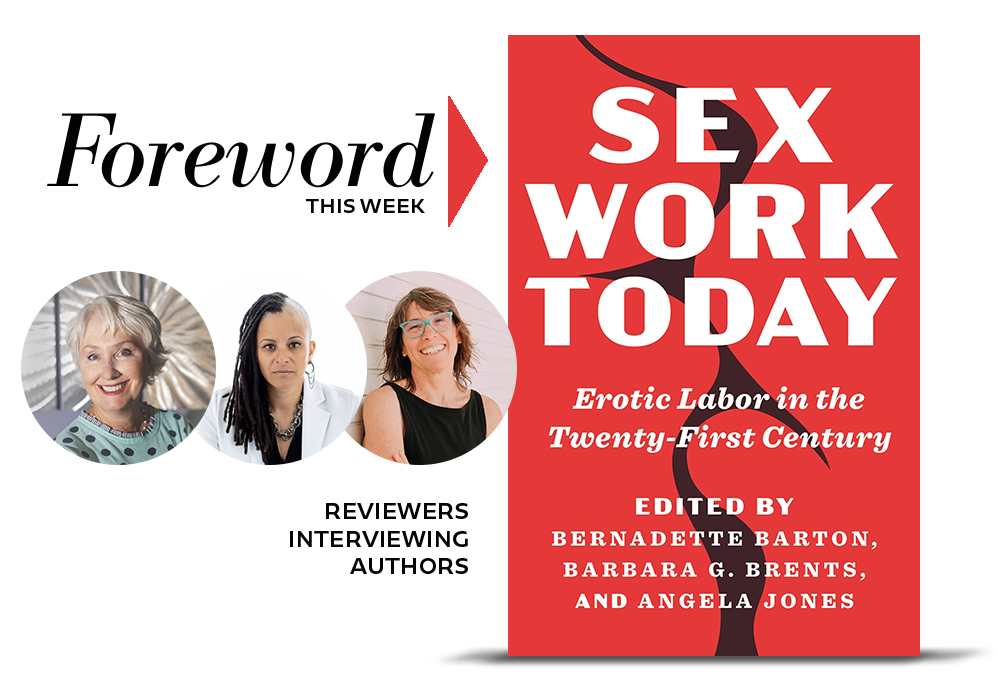

Reviewer Eileen Gonzalez Interviews Angela Jones, Barbara G. Brents and Bernadette Barton, Editors of Sex Work Today

“Sex workers face rampant occupational discrimination, especially in banking and financial systems. American Express, CashApp, Chase Bank, Paypal, Wells Fargo, Venmo, and others already refuse to process payments for sex workers across erotic industries, including porn, which is legal in the US. … Sex workers are systematically being cut off from an entire financial system, which has implications for housing, credit, insurance, and their ability to survive.’’ —Jones, Brents, Barton, Sex Work Today

University presses are indispensable—today’s featured book and interview showcase why. Can you imagine a big profit-driven corporate publisher bringing to market a title like Sex Work Today? Not a chance. Only the “greater good” mindset of university presses like NYU Press see the value in publishing an important collection of essays focused on the “challenges faced by those engaging in modern erotic labor.”

For all of us in the books industry, it’s a necessary reminder that “units sold” is not the best way to measure the worth of a book; “minds changed” and “lives bettered” is the heart of the university press publishing mission, to the benefit of all.

Speaking of “it could only be from a university press,” we also covered Dodge County, Inc.: Big Ag and the Undoing of Rural America, a title from the University of Nebraska’s Bison Books, in our November/December issue (PDF here, page 61). Your free digital subscription entitles you to 100+ reviews of university press and independently published books six times a year—subscribe today.

Where did the idea for this anthology come from, and how did you decide that the three of you should work together to make it a reality?

Bernadette began teaching a course on the sex industry shortly before the publication of her first book, Stripped: Inside the Lives of Exotic Dancers (2006). Cross-listed with Sociology, Criminology, and Gender Studies, “Perspectives on the Sex Industry” is a very popular class with students. As Bernadette patched together readings year after year, she wished for a book that combined a variety of dimensions on sex work that she could use in the classroom. Bernadette reached out to New York University Press to see if they were interested in such a volume, and her editor, Ilene Kalish, responded enthusiastically. Bernadette then invited Angela and Barb to join her as editors because she highly valued their work on erotic labor and thought they would bring many intellectual and social resources to the project. They accepted, and we began work on Sex Work Today in the spring of 2019.

We share a professional and personal commitment to improving the lives of sex workers. This does not mean sugar-coating issues in the industry. Sex Work Today includes a robust critique of political hierarchies and the systems of power, such as capitalism, white supremacy, heteropatriarchy, ableism, and cisgenderism, that shape labor experiences and the issues that workers face. Further, we are attentive to how issues such as shadowbanning, police harassment, and various forms of labor exploitation are exacerbated for marginalized sex workers.

We can’t say enough about how much we appreciate one another as a team. Creating an edited anthology is a different kind of work than writing a solo book. There are a lot of details and moving parts. We have been generous, kind, and hardworking with each other, pooling our skills, time, and resources to manifest Sex Work Today during a global pandemic.

You mention that you first started receiving paper proposals for Sex Work Today at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. How did that affect the process of sharing your thoughts with each other on each piece and putting the book together?

As mentioned, we began a discussion about Sex Work Today about a year before the pandemic and released a call for papers in November of 2020. In other words, we were ankle-deep in the project when the world shut down. We certainly benefitted from improvements in video technology and did much of our work over video calls. Sometimes, we were the only ones we saw in a day besides our families.

Working on Sex Work Today also helped anchor us to our work, scholarship, and activism through and after the pandemic. We received a few submissions exploring the effects of the pandemic on sex work. The book includes a discussion of the mutual aid networks that emerged during the pandemic that were a lifeline for many.

Can you share a little about studies or papers you didn’t have room for in this collection but would have liked to include if you were able?

The response to our call for papers was impressive, and selecting essayists based on abstracts was tough. We were bound by space and publisher word count limits (which we still exceeded), and we were sorry we could not take more submissions. As editors, we had four interrelated priorities that shaped the selection process.

First, we strove for inclusivity regarding sex work industry segments, worker subjectivities, and geographical and cultural contexts. Second, we prioritized the ethical inclusion of sex workers, wanting to ensure that we were accepting as many papers as possible written by former or current sex workers. Third, we looked for essays where authors grounded analyses in intersectional and transnational frames. Fourth, we wanted to ensure all papers engaged with stratification systems within the industry itself, attending to what sex workers call the whorearchy and lateral whorephobia. In an expansive erotic labor market, a worker’s identities, alongside the industry segment they work in, shapes their labor experiences in uneven ways.

Given the transnational character of sex industries and the scope of global sex worker activism, alongside the US and UK focus on sex work research, we aimed to cover a wide range of international contexts. The chapters in the volume cover sex work in Canada, Kenya, New Zealand, the United States, and the United Kingdom. We wish we had received more submissions from people laboring in or writing about the Global South and street-based economies, and we hope to see more future work capturing these contexts.

The papers in this book cover such a wide array of topics from very different writers and researchers who have studied and/or been involved in all aspects of the sex industry. Based on what you learned from these diverse opinions and conclusions, what would you say is the most urgent action that should be taken to protect sex workers today?

The sex industry today is expansive. The internet has diversified sex industries and expanded available forms of erotic labor. So, while all sex workers face labor rights issues, the nature and experience of issues vary widely based on what industry segments they work in and their social locations or identities within overlapping systems of oppression. With this said, stigma or whorephobia is pervasive, and criminalization, censorship, and discrimination are significant issues that harm sex workers every day.

A few of the most urgent issues requiring redress are related to criminalization and repealing other harmful laws such as FOSTA/SESTA, occupational discrimination, protecting online privacy, and addressing harmful new regulations of sex work online. There are rising calls in various nations for a move to End-Demand Models, which criminalize clients only. There is a need for more education about how this legal model harms sex workers and how the decriminalization of sex work reduces harm, improves relationships between workers and law enforcement, and improves public health outcomes.

Sex workers face rampant occupational discrimination, especially in banking and financial systems. American Express, CashApp, Chase Bank, Paypal, Wells Fargo, Venmo, and others already refuse to process payments for sex workers across erotic industries, including porn, which is legal in the US. Some cancel sex workers’ bank accounts if they suspect they labor in the sex industry. Sex workers are systematically being cut off from an entire financial system, which has implications for housing, credit, insurance, and their ability to survive.

Finally, the increasing political influence of far right-wing politics and anti-sex work crusaders and activists has led to the introduction of new policies and regulations that are not at all helpful in addressing labor trafficking yet produce censorship and online privacy violations that should concern everyone.

What surprised you most about either the essays themselves or the process of compiling them?

One of the most surprising and rewarding aspects of compiling this book was the incredible diversity of perspectives, experiences, and writing styles in each chapter. We anticipated a range of voices, but we were continuously impressed by how each author brought unique insights from different industry segments to illustrate how inequalities and intersections of race, class, and gender shape the issues sex workers faced.

As indicated above, another pleasant surprise was how well our editorial team worked together. Curating such diverse content required extensive coordination and sensitivity, and the collaboration between editors and authors made the process especially rewarding.

Overall, this experience has been both inspiring and enlightening. It has been a true privilege to provide space for such a wide range of voices in the ongoing discourse on sex work.

You and others in the book talk about how the sex industry is changing rapidly, both for better and for worse, thanks to advancing technology, shifting public sentiments, and public health crises. Given that, how do you think this book would have looked different if you published it ten years ago? How about if you published it ten years from now?

Ten years ago, we would have held our editorial meetings on Skype! Technological change transforms the industry, even since our initial call for papers, but it always has. We couldn’t have predicted how the COVID-19 pandemic would reshape sex work. But, ever entrepreneurial, sex workers have continuously adapted to changing legal, cultural, and technological landscapes, so the chapters would still have shown how they were at the cutting edge of these trends. However, there was no FOSTA/SESTA a decade ago. Without this 2018 law, which conflates voluntary sex work with trafficking, sex workers had more opportunities to work independently and safely online. Activism within the industry was also more fragmented; FOSTA/SESTA unified a broad coalition of advocates from diverse sectors who have since lobbied for policy change, even while facing an increasingly organized anti-sex work movement.

Looking ten years ahead, we hope a future edition of this book will reflect meaningful progress and even more organized pushback against anti-sex work policies. We envision politically active, diverse sex workers shaping policy and contributing to academic discourse, alongside advances in labor rights and social protections. Yet, systemic inequalities like capitalism, white supremacy, and heteropatriarchy will likely continue to shape the landscape, meaning future editions may still need to address how these forces impact sex work and the ongoing fight for equity.

Eileen Gonzalez