Reviewer Eileen Gonzalez Interviews E. Patrick Johnson, Author of Honeypot: Black Southern Women Who Love Women

Consider us fanatical book people here at Foreword, always on the lookout for fantastic new projects to review for our librarian readership. In case you were unsure, the main reason we only review books from independent and alternative publishers is the fact that these indies are bringing to market the most intriguing, unexpected, extraordinary titles in the industry. Moreover, we’ve spent enough time chatting up acquisition editors at book events over the years to know that the indie ethic includes a fierce determination to publish important books.

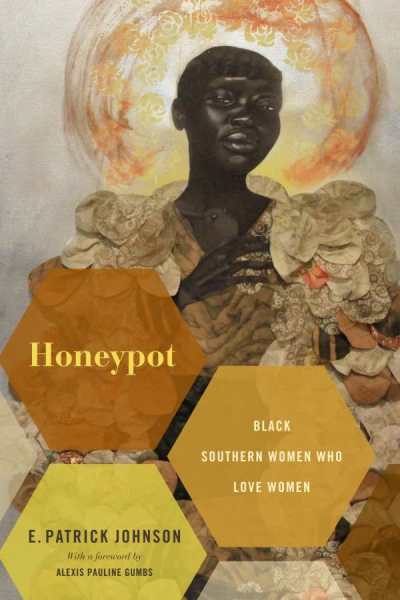

This week’s interview showcases Honeypot: Black Southern Women Who Love Women, from the intrepid staff at Duke University Press in Durham, North Carolina. This was a story that needed to be told.

Eileen Gonzalez reviewed Honeypot in the pages of Foreword’s November/December issue and with Duke’s help, we connected Eileen with E. Patrick Johnson, Honeypot’s author.

Eileen, you’re on.

Honeypot‘s approach to oral history is really memorable and unique. You cast yourself as Dr. EPJ, who is kidnapped by a trickster figure, Miss B., and taken to the fictional realm of Hymen, where queer Southern black women reside. Obviously, you’re using a fictional frame to tell these women’s true stories. Why did you decide to use this approach? Do you think there are advantages to this format versus more traditional ones?

My decision to create a fictional frame to tell these stories emerged from the process of conducting the oral histories themselves. The word “honeypot” was a term that I frequently heard from the women—a word whose reference I was unfamiliar with. This sent me down a path of doing research on honey and honeybees. The more I learned about honeybees, the more parallels I discovered between their lives and the lives of the women I had interviewed. It made sense to me, then, that I should try to create a world where these stories could live outside a literal place and be shared in a mythical space.

And, because some of the women I interviewed practice Yoruba religious practices or other non-Western forms of spirituality, it made sense to incorporate mysticism into the rendering of these stories. I also wanted a way to allegorize some of the challenges of conducting oral history and ethnographic research across the gender divide. Miss B. and Dr. EPJ’s relationship gave me a way to do that. The fictional frame, therefore, gave me a way to do that without being too literal or didactic.

The women you interview are all very forthcoming with their thoughts and histories. Some stories are uplifting and joyous, while others are explicit and/or dark enough to make EPJ uncomfortable. Why was it so important for you to preserve and relate this spectrum of experience?

No community is monolithic. Thus, it is important to show the broad range of experiences and views across the spectrum of those who express same-sex desire. Because these women are from different parts of the South, naturally their experiences vary according to the region in which they were born and continue to reside. Nonetheless, some common themes exist across the board.

You interviewed seventy-seven women for Honeypot and, from that total, included dozens of their stories in the book. Was there any story or theme in particular that stuck out to you?

All of these stories are powerful in their own way and for different reasons. The stories of the “elders” in the last chapter of the book are the ones that captivated me the most, however. I suppose that is because these women’s stories in particular were so compelling based on the tremendous obstacles they faced—surviving abject poverty, sexual trauma, drug addiction, and incarceration. The fact that they came out on the other side of these experiences whole is a real testament to their fortitude.

You’ve written another book, Black. Queer. Southern. Women., that uses many of the same oral histories featured in Honeypot. Were there any differences in your experience writing Black. Queer. Southern. Women. versus Honeypot? For example, was one more challenging, either emotionally or technically, than the other?

These started out as one book. Then, my editor at the time suggested that I write two different books—one that was more of a traditional oral history and the other more creative nonfiction/performative. Black. Queer. Southern. Women. is a lot longer and was a bit more challenging to write because of all of the ground I had to cover for other academics. Honeypot presented a different set of challenges because it was my first attempt at creative writing. I really enjoyed and had a lot of fun writing the characters of Miss B. and Dr. EPJ and creating the world of Hymen, but I also found myself working extra hard to make the writing evocative and engaging to readers.

In the end, EPJ’s guide, Miss B., reminds him of the importance of speaking truth, and of how it is both a “gift” and a “burden” to tell others’ stories. Could you expand on these ideas? What do truth, and the gift and burden of telling these women’s stories, mean to you?

When someone shares their story with another person, the “gift” is the trust the teller endows the listener with to bear witness and hold the space for the telling. The “burden” reflects the responsibility of the listener to hold the story and, if shared with others, to do so in a way that is ethically and morally responsible. For me, the goal of bearing witness is not to access “a” truth, as in facts, but rather to allow someone to share their truth as they experienced it.

And finally, what do you hope readers take away from Honeypot?

I hope readers gain insight into the lives of a community of women who are not always valorized in our society. I also hope, through the relationship between Miss B. and Dr. EPJ, that like Dr. EPJ, readers become self-reflective about how they participate in patriarchy—sometimes unwittingly—and how one can grow once they develop a consciousness around issues. Fiction, I believe, is sometimes a powerful form to lead readers to a place of transformation.

Eileen Gonzalez