Reviewer Eileen Gonzalez Interviews Lin Enger, Author of American Gospel

His papers don’t mention it but we wonder if Charles Darwin ever thought about factoring God into his theory of evolution, because when you look back over the tens of thousands of years of human existence, God has definitely evolved—from the many deities of mythology in ancient times to the different lead roles they play in any number of major and minor religions to the countless other divine variations imagined by believers outside the mainstream.

Yes, Darwin could have easily subjected God to the natural-selection treatment—it’s plain to see that as the cultural environment changed in society, God changed. They might be wrathful or all-loving, militaristic or pacifist, or just about anything in between depending on a multitude of localized factors.

Thanks for indulging our little theoretical excursion but we were led down this path by a few provocative comments about religion from Lin Enger in this week’s interview with reviewer Eileen Gonzalez. Below, Lin talks about how American culture has hijacked the good word of the lord. He says, “I see American churches as institutions more interested in propagating American values (individual accountability, a strong work ethic, conventional behavior) than gospel virtues (humility, selflessness, commitment to the common good). Also, American churches—as distinct from Christian churches abroad—have long been obsessed with the idea of apocalypse; church leaders, especially in the Evangelical community, are fond of projecting eschatological scriptures onto current events, with (I think) often humorous results.”

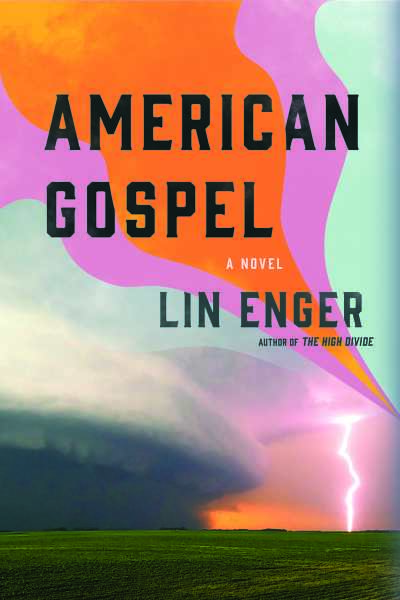

These are the types of observations that lead to compelling storytelling, and in her starred review for the November/December issue of Foreword, Eileen confirms that Lin has the chops. She writes, “American Gospel a glorious novel about what people choose to believe—and, more importantly, why they choose to believe it.”

We wanted to hear more about Lin and his latest novel, so with the help of the University of Minnesota Press, we set up the following fascinating conversation.

Eileen, take it from here.

American Gospel’s overarching theme is belief: who believes what and why, and how internal and external factors can affect belief. Do you see these topics as timely or timeless?

Timeless, certainly. The need to explain to ourselves who we are, where we come from, where we’re going, and what it all means is ever-pressing and ongoing. Although each person may be able to answer these questions in ways they find more or less satisfying, there are no conclusive explanations. To be human is to live with ambiguity.

In America, though, questions about what and how to believe are timely as well, because the sources of fact and truth that we have long consulted and respected are in the process of fragmenting and losing their authority. The media is breaking apart into ghettoized groups that cater to the demands of their various audiences instead of offering objective, carefully curated news. Churches have betrayed the people they’re supposed to serve in multiple ways—abusing children, selling out to political parties, and propping up the status quo instead of focusing on matters of spirit and human need. More to the point, at this very moment, government leaders at the highest level are actively and publicly working to undermine the democratic principles on which this country was founded. The recent election, which was not even close by historical standards, is being called fraudulent by a president and a party that would rather tear the system apart than concede defeat. In my lifetime, there has never been a moment in which factual truth has been more endangered.

Going off the last question, American Gospel is set in the American Midwest during the end of the Nixon administration. This was a time of great uncertainty, disappointment, and disillusionment in the United States. Why did you decide on that setting as the best one for this story?

In the 1970s, Americans woke up to the fact that they had been deceived for years by their leadership: first Vietnam, and then Watergate. It was a time of great disappointment and disillusionment. It was also a time when the country was obsessed with apocalypse: fear of nuclear war, fear of environmental disaster, fear of Armageddon. The bestselling nonfiction book of the entire decade was The Late Great Planet Earth, which made the case that Christ’s return to Earth was imminent.

I had to decide, in planning this book, whether to make it contemporary—set in the present or near future—or to imagine it as happening in a previous time. I chose the latter in part because I didn’t want readers to be thinking, as they read along, “Is the Rapture really going to happen?” Instead, I wanted them to think, “This can only end badly—but how?” Anyway, the 1970s seemed perfect for the reasons mentioned above; the novel presents a microcosm of a society in which people are being deceived by lies they would like to believe are true. Finally, the 1970s was an era that I knew well—it was the decade I came of age.

Each of the three main characters represents different aspects or levels of belief. Enoch’s whole identity revolves around his religious faith, Melanie wants to learn how to have faith again, and Peter is very cynical. Is there a character that you identify with more—or, at least, that was easier for you to write—than the others? Which was the most challenging?

I find aspects of all three main characters in myself, but the one with whom I most identify is Peter, who is compelled to resist the imposition of his father’s dogmatism. For me as an artist and a believer, writing the novel was an exploration of the tension that exists between dogma and mystery; it is my attempt to dramatize how the insistence and assertiveness of rigid belief systems are an enemy of faith. In some essential ways, I am Peter. And I have known many Enochs—men and women absolutely certain (or so they tell themselves and others) that they have arrived at the final answers to the largest questions. As for Melanie—who wants and needs to believe that Enoch’s prophecy will rescue her from the life she’s drowning in—she may have been a bit harder for me to write, though haven’t we all felt ourselves drowning at one time or another?

The title, American Gospel, is very intriguing. Did you come up with it before or after the rest of the story? And what do you think it says about/contributes to the story as a whole?

I didn’t arrive at the title, American Gospel, until well after I’d finished the novel. My working titles were “American Whirlwind” and “The Translation of Enoch Bywater.” I still like those earlier titles, but it became apparent to me that they didn’t capture the essence of the book’s subjects or themes.

I like the title American Gospel for several reasons. The word “gospel” comes from the Anglo-Saxon “god-spell,” which translates to “good story.” And in this case, the story—as I see it—is about the way the gospel, in America, has been hijacked by American culture. I see American churches as institutions more interested in propagating American values (individual accountability, a strong work ethic, conventional behavior) than gospel virtues (humility, selflessness, commitment to the common good). Also, American churches—as distinct from Christian churches abroad—have long been obsessed with the idea of apocalypse; church leaders, especially in the Evangelical community, are fond of projecting eschatological scriptures onto current events, with (I think) often humorous results.

It would be easy to laugh at Enoch’s apocalyptic predictions, but there is also something tragic about his and others’ desperate need to believe in something, no matter how unlikely. How did you strike the right balance of making clear the absurdity of the situation without mocking the characters or turning them into parodies?

I hope readers will laugh at Enoch. I think he’s hilarious—in the way anyone is who takes himself as seriously as Enoch does. I also admire him. But he scares me, too, as those people I’ve known in life who resemble him scare me. It was not difficult for me to write Enoch without mocking him, because as I said, he is someone I know. He is many people I have known. And most of them I have respected and even loved.

What I’m trying to say is, I take him seriously. He is not simply a fictional character to me. He is a man with obvious flaws (grandiosity and tremendous pride) and beautiful strengths (persistence and courage). As I imagine him, he is a man who mostly believes what he claims to believe; when doubt creeps in, he pushes it away in the manner believers are encouraged to do. He is not malicious. He is not consciously deceiving anyone—however, over long years of misunderstanding what faith is, he has come close to losing a key ingredient of being human: humility. And for that reason, he has become very dangerous. I never lived in a religious commune, but I knew people who did, and I spent a lot of time in close proximity. In writing this novel, I simply dramatized that experience.

Eileen Gonzalez