Reviewer Erika Harlitz Kern Interviews Costanza Casati, Author of Clytemnestra

Ancient Greek mythology haunts literature like a recurring dream, drifting in and out of countless works of writing over more than thirty centuries—the Bible, Roman tragedy, Viking saga, Shakespeare’s plays, James Joyce’s novels, Margaret Atwood’s The Penelopiad, only to name a few notables.

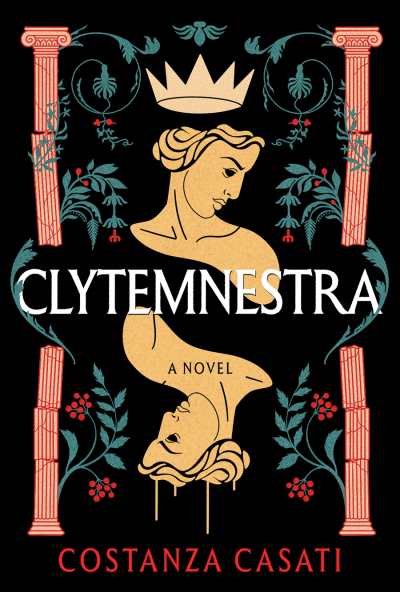

This week, at the urging of Erika Harlitz Kern, we’re pleased to add Costanza Casati’s Clytemnestra to our list of all-time favorite gifts from the Greek gods.

Calling it a “a great literary achievement that gives voice to characters who, due to their genders, have been vilified and silenced throughout the millennia,” Erika honored Clytemnestra with a starred review in Foreword’s January/February issue, and, true to form, Foreword This Week provided the venue for a splendid conversation.

First of all, I just want to say that I love your novel Clytemnestra. Reading it was an amazing experience. It is a fantastic deep dive into the psyche of Clytemnestra, arguably one of the most vilified characters of Ancient Greek literature. I am personally a big fan of Clytemnestra, so I was very happy to see that here is an opportunity for her to tell her side of the story, and that it was done so well.

With that as our starting point, I was wondering if you could talk a little bit about how you went about getting into the minds and hearts of the characters of the book, in particular Clytemnestra, but also some of the side characters. Odysseus, for example. He is a side character, but you have him down to a T. Same thing with Penelope, whose intelligence and cunning really shine through.

I’ve always loved Clytemnestra, and I have been obsessed with her for years. And I think that, to really get into the mind and heart of your main character as a writer, you need to be obsessed with them, to think about them constantly. There are so many sentences from the ancient texts that helped me understand what kind of character Clytemnestra was. In the Oresteia, the trilogy of plays by Aeschylus, the chorus of Mycenae calls her “full of self-command,” “our lone defender, single-minded queen.” The elders say that they respect her power, using the Ancient Greek word kratos, which means “political power” and isn’t normally associated to a woman.

In those plays she is resolute, unbending, cunning and treacherous. There are so many instances where she plays with words to trick her husband as he comes back from the war: “search, my king, and learn at last who stayed at home and kept their faith and who betrayed the city.” Other accounts show different sides of her: if she’s a power-hungry ruler in the Oresteia, in Iphigenia in Aulis she is first and foremost a loving mother, and the play even includes a mention of Clytemnestra’s first husband, a king by the name of Tantalus, whom Agamemnon murdered to have Clytemnestra for himself. So to really capture her character, I wove together different accounts of her, while also digging into her backstory as much as I could.

As for the other characters, some of them are not really well known—Timandra, for instance—so I had more freedom in writing them. Others—Odysseus, Helen, Penelope—are incredibly famous, and so I tried to depict them in ways that were both true to the sources but also felt fresh. Odysseus is one of the most famous heroes of all times and, as such, has been reimagined hundreds of times. What all depictions have in common is that he is a cunning trickster. That makes him both charming and brutal, and I wanted both aspects of his personality to come out in my novel. After all, in the Odyssey, he always gets his men in trouble because of his ambition, arrogance, and curiosity (think about his meeting with the Cyclops) and in the Iliad, he is someone who would do anything to win the war: from ruthlessly killing the enemy soldiers he’s promised mercy to, to thinking of the great wooden horse to trick the Trojans. I’ve always seen him as a true Machiavellian character: he truly believes that the ends justify the means.

Penelope can be an equally tricky character. The narratives around her have always been more feminine—she is defined by her loyalty and patience, and her life is bound to the man she marries. In my novel, she is wise and clever, but she is not all light—there is darkness inside of her too. One of my favourite lines of hers is in the letter she writes to Clytemnestra after Clytemnestra’s child is sacrificed, when she asks her to forget what has been done to her: “In truth we must suffer, in lies we can prosper.”

Another character that also gets her moment is Helen, Clytemnestra’s sister, also known as Helen of Troy. She gets the blame for the Trojan War, which becomes connected to her moral character. But here you present her as a fully fleshed out woman, who comes into her own as a person when she demands her husband Menelaus’s respect by making the entire world go to war. This is a new interpretation of Helen for me, and I was blown away by it. Could you talk a little bit about how you see Helen as a character?

I always felt like Helen has been so famous throughout the millennia, that she had become too mythical to be portrayed in a human way. In order to ground her, to make sure she felt as real and human as possible, I went back to her childhood in Sparta, the kind of training she must have gone through—she wasn’t physically strong in a world that valued strength and brutality above all—and her relationship with her family. More specifically, the two elements that I focused on in her backstory and that made her who she is in the novel, are Theseus’s abduction of her, which is documented in many sources but rarely studied or talked about as a rape, and the fact that she is not Tyndareus’s legitimate child, but rather rumored to be the offspring of Zeus, who impregnated Leda in the form of a swan. How would that have affected her, I wondered. She is someone everyone loves and thinks beautiful, but how does it feel not to have the love of a parent?

Going back to Clytemnestra. In the Greek texts, Clytemnestra is put forward as an example of how a woman should not behave, something that tends to carry over into our modern readings of her. But in your novel, you took another route and instead presented Clytemnestra as a person with a genuine backstory and deep personality. What made you decide to write a novel from Clytemnestra’s perspective? What was it you wanted to say by making that choice?

What I love the most about Clytemnestra is that she is a woman who sees herself as equal to the men around her and who would do anything to protect the ones she loves. For me, she is a good person, and I believe it was important to write her thinking she was a good person at heart, even when she did bad things, otherwise the novel wouldn’t have worked.

As you say, modern readings of Clytemnestra tend to depict her in a negative light, as the archetypal bad wife: a lustful murderess who doesn’t know her place. While I was writing my novel, I was really interested in the contrast between how she perceives herself and how others perceive her. There’s a quote towards the end of the book that says, “Heracles, Perseus, Jason, Theseus … songs about them are sung, and their cruel deeds are turned into sunlight. As for queens, they are either hated or forgotten. She already knowns which option suits her better. Let her be hated forever.”

Throughout the novel, Clytemnestra is aware that her deeds aren’t considered heroic, because she is a woman, but she doesn’t care. This is something that comes across even in the ancient texts. Two of my favourite quotes are from the Odyssey and Agamemnon. The first is by Agamemnon, the second by Clytemnestra, and both talk about her murder of her husband. “There’s nothing more deadly,” he says, “bestial than a woman/ set on works like these––what a monstrous thing/ she plotted, slaughtered her own lawful husband!,” while she says: “I brooded on this trial, this ancient blood feud/ year by year. At last my hour came. / Here I stand and here I struck/ and here my work is done.” He thinks her bestial, she thinks herself heroic.

Clytemnestra is most famous for her relationship to Agamemnon. Traditionally, Agamemnon is considered a hero in the Ancient Greek meaning of the word, and as such, he gets a pass for a lot of the things he does. Meanwhile, Clytemnestra, as a woman, is vilified when she does similar things. I read Clytemnestra as a Greek hero just as much as Agamemnon. Would you call Clytemnestra a hero?

The Greeks didn’t use the word “hero” as we do today; for them, heroes weren’t necessarily people with integrity, generosity, courage, but rather figures who were bold and arrogant, powerful and sometimes narcissistic, who thought themselves better than everyone else (just think about Achilles, Jason, Theseus). Agamemnon was definitely a hero in the eyes of his people, but at the same time, he is always portrayed as a bad person, even in the Iliad and the Odyssey. He is someone who steals his warriors’ prizes, who humiliates his slaves, who kills his own daughter for a puff of wind.

In the play Agamemnon (the first in the Oresteia trilogy), Clytemnestra is the main character, despite the title of the play. As I set out to write this novel, I knew I didn’t want to write a story that gave voice to the voiceless—because Clytemnestra had a voice. But rather it was about writing a woman who took part in the action, whose deeds are as complex, epic, and heroic as the ones of the men around her.

Clytemnestra and Agamemnon are what you could call a power couple, although a dysfunctional one. In your novel, you really succeeded in getting to the core of what makes them tick as a couple. How would you describe them as a couple, and what do you think they can tell us about what it means to be human today?

There are a lot of layers to their relationship. Clytemnestra hates him (rightfully so) and will never forgive him, but I think they both crave power and they both know how to rule. Agamemnon is obviously a far worse person than his wife, but I do think that he loves her in his own strange way, which is deeply selfish and arrogant. He is the kind of man who is attracted to strength, but still wants to be in charge. In a line in the novel, I say, “He desired her strength because it was a challenge to him. He wanted to show he was stronger by subjugating her.”

And I think that this is an example of how, in many ways, the characters in the novel reflect real people in our contemporary world. Many of the things Clytemnestra and other women from the myth endure, women endure today. At the same time, the ambition she has and feels isn’t something that women felt only in Ancient Greece. These mythical stories might be ancient, but I see the characters in them as some sort of heightened version of the men and women that are in our own lives.

Erika Harlitz Kern