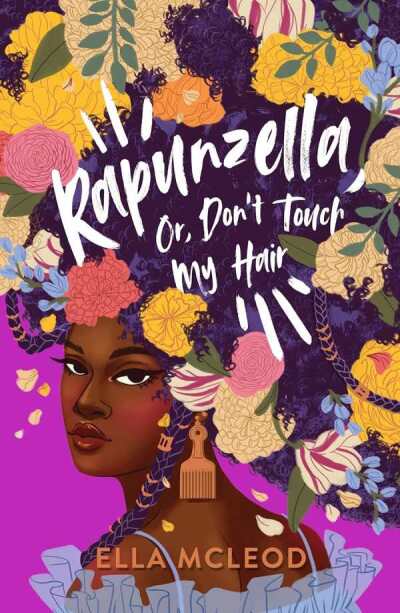

Reviewer Isabella Zhou Interviews Ella McLeod, Author of Rapunzella, Or, Don't Touch My Hair

“I think black women move through the world often feeling powerfully othered. In the west, the vast majority of our media … does not centre our experience. We are sidecharacters and footnotes in history, if we are to be found at all. There is this bizarre perception that audiences and readers ’can’t relate’ to stories that centre blackness, which is truly wild when you think about how many stories there are that centre talking animals.’’ —Ella McLeod

Around here, we like to say that librarians threaten ignorance, using books as their weapon of choice.

We also frequently remind ourselves that books threaten people with power—because books dare to imagine a different reality, one where authority is challenged and the once powerless rise up to take their place at the table of equality.

Ella McLeod is with us today to talk about Rapunzella, her dangerous new reimagining of the Caribbean—where Black witches and empowered Black girls with glorious hair use Indigenous magic to rise up against their enslaver, King Charming. An expert in fairytales and myth, Ella is drawn to the rhythms and lyricism of oral traditions, so she alternates prose and poetry in the sections of Rapunzella. In the interview with Isabella Zhou below, Ella says, “there are images and feelings that poetry can invoke that are just so magical and I really wanted the worlds to feel separate—until they aren’t.”

Catch Isabella’s starred review in Foreword’s July/August issue here.

You revise and build upon many beloved fairy tales and myths—those from the Western canon as well as the Black Caribbean ones that, as you reveal in your author’s note, you heard while growing up in the UK. How did you choose which stories to retell? Did you decide on them beforehand or did they organically weave themselves into the story as you were writing? And how did you put them all together into a cohesive whole?

The story of Rapunzel was where I started, of course. The first drafts of what would become Rapunzella were initially my dissertation in my final year of university and started out as a 5k-word, spoken-word poem and a 5k-word essay. I wanted to interrogate the historical, political, and cultural significance of black hair and have always been interested in what myths and fairytales and folklore tell us about our world.

Rapunzel was such an obvious starting point because hair is so central to the story. A white, European princess is physically liberated by her long straight hair. Conversely, I had spent my whole life absorbing messages—from the media to little comments made by people in my life—that my hair was too thick and too dark and too coarse. The implication of undesirability is one that most black women can probably relate to. From there I began the journey of building out a narrative that subverts fairytale norms with the intention of using magic to imagine an Afro-Caribbean reality that is able to sit powerfully outside of western colonisation. I wanted to pay homage to the elements of indigenous storytelling that had been suppressed or erased or appropriated and combine those things to acknowledge the uniqueness of the diasporate experience. Being from lots of places—feeling sort of rootless as a result—and then being rooted in that blended place. The process was pretty organic and I had to cut quite a lot, in fact a lot of what I cut has gone into my second book The Map That Led To You, which came out in the UK in April. The River Mumma, for example, features in Rapunzella but I really wanted to expand her story as hers was one of my favourite tales that my grandmother would tell me.

Black women’s hair is central in Rapunzella. It is the source of the witches’ power in Xaymaca and representative of their collective resilience, history, and culture. The narrator’s own struggles with coming-of-age as a young black woman are embodied, in part, by her decision to straighten her hair, a decision that is interrogated by her friends in Xaymaca. What would you say to Black girls who are themselves currently going through adolescence and struggling with self image in a world saturated with white, European beauty standards? What is the significance of these themes in a politically and culturally charged contemporary moment that is still often hostile to black women and their bodies?

Firstly—you are beautiful. Secondly—you are so much more than beautiful and your worth is not related to your desirability. The fact that you feel this way is not your fault. There is a wider context here, a long, racist, colonial history and a capitalist agenda that benefits from you feeling inferior. Ultimately, your journey into self-confidence is not one I can take for you and is one I am still going on. But for me, reading widely on this subject was intricately linked to healing. A Raisin in The Sun, by Lorraine Hansberry, Queenie, by Candice Carty Williams, anything by bell hooks or Maya Angelou … Realising that many black women had been where I was before me and had found a way through was heartening. It’s not so much about deciding to straighten your hair or not straighten your hair, as much as it is finding choice empowering not oppressive. There is no right or wrong answer but I do believe it to be important that we keep asking ourselves questions about why we’ve decided to wear something or say something. What do we assume about ourselves every day? Can we give ourselves the grace of making a decision for ourselves without being constantly preoccupied by the perception of others?

So much of my personal unpicking of the damage done by racist beauty standards was tied to gaining a broader understanding of liberation politics, which I suppose answers the second part of this question. At the moment, whether looking at the horrifying statistics around the world that show how black women are still so vulnerable to violence, or discussing the right of trans people to gender-affirming care or the ongoing battle around Roe vs Wade, the fight for bodily autonomy wages on. Women, and black women in particular, are disproportionately affected by this. Yes, our hair and the denigration of our hair is important, but hair here is also a stand in for a wider conversation about what we are entitled to and what the structures of capitalism and patriarchy, as well as the legacy of colonialism, strip from us. I really wanted to sew the seeds of these questions in the minds of young people.

What happens with Prince Charming’s takeover of Xaymaca parallels many of the terrible injustices of history—slavery, colonization, the exploitation of black bodies, and their lasting effects in the present. The narrator’s waking experiences also touch upon many contemporary problems—homelessness, poverty, urban colonization in the form of gentrification. However, Rapunzella makes room for joy: the witches celebrate the Great Strike that first liberated them from Prince Charming, even though he has repossessed his power, and the interspersed poems are often celebratory odes of the witch’s great deeds. How were you able to balance hope and despair? How do you celebrate triumph while acknowledging the terrible legacies of slavery and racism that persist in the present? What is the role of joy in overpowering evil and confronting injustice?

I think community is at the heart of this, for me. My family, my friends, the absolute gift that is love and loyalty and sensuality. We are most powerful when we find commonality with others and it is through celebration that we do this best, I think. Rituals and traditions that allow us to come together and be grateful and enjoy each other are so important to building the kind of solidarity and unity that fuel movements. I honestly wrestle with hope and despair every day and cynicism is far, far easier than faith.

In moments of real nihilism, I think of two things. Firstly, I fundamentally believe that people are good and it is their material conditions that make them do bad things—whether those conditions are lack of excess or an indoctrination into entitlement. I believe that our capacity for love is incontrovertible proof that we are, at our cores, joy seeking, pleasure seeking creatures and that it is possible to build a world where one person’s joy does not mean another person’s despair. All of the terrible terrible things that happen in the world are still within our power to change.

The second thing I think of is my friend Celina, who the book is dedicated to. She passed away when we were twenty-one and was ill for a lot of her life. She was the shiniest, most optimistic, joyful, mischievous person, despite going through so much. I am often not a gracious person—I am petty and defensive and am often very angry. I would never have handled the end of my life, and all the suffering she endured, the way she did. And so every time I find myself falling back into cynicism and despair, I think “how dare I, who is so privileged and safe, give up on the good of people and the hope for the future? Who will be hopeful, if not I, and people like me—middle class and educated and loved and healthy?”

And so this was vital to this story. Joy and love allow us to endure—what else would the witches fight for if not the chance to live joyfully in a better world?

I am curious about your story’s narrative perspective—it is from the point of view of a girl whose name we only learn at the very end, who makes the profound realization that she is perhaps “not the main character of this story.” But we are also invited to identify with her through the “you” perspective and empathize with the intimate chronicling of her experiences, even when she makes mistakes that hurt those she loves. Why did you decide to tell Rapunzella’s prose sections from this unique narratorial perspective?

I think black women move through the world often feeling powerfully othered. In the west, the vast majority of our media—especially when I was growing up in the 00s and 2010s—does not centre our experience. We are sidecharacters and footnotes in history, if we are to be found at all. There is this bizarre perception that audiences and readers “can’t relate” to stories that centre blackness, which is truly wild when you think about how many stories there are that centre talking animals. I wanted my young black girl readers to feel aggressively represented and I wanted anyone whose experience does not align with my protagonist to be forced into a kind of radical empathy—to really have to put themselves in our shoes.

Also unique about Rapunzella is the alternation between sections of prose with poetry. Why did you write your book in this genre-weaving format?

I wanted to pay homage to the rhythms of certain forms of storytelling, the lyricism of a more oral tradition, for example, and blend that with classic, western fairytales. I also think there are images and feelings that poetry can invoke that are just so magical and I really wanted the worlds to feel separate—until they aren’t.

Your book is filled with strong though flawed black women, girls, sisters, mothers. Who did you most enjoy writing, and who was the most compelling to you, as the author? What do they say about black femininity?

That’s really hard. I love them all to be honest. Obviously, the protagonist is very special to me because she’s so flawed but has such a good heart. I put a lot of myself in her, my own insecurities and difficult teenage trials and tribulations, but we handled things very differently and it was fun to write that. But I think Kamaka is my real favourite. She’s spiky and angry and so, so brave. I love her. In regards to what they say about black femininity, I think everything and nothing and that’s sort of the point. We’re not a monolith. Our experiences are different and even when they’re not that different they are.

Can you talk a bit more about the villains of Rapunzella? Almost all the evil in the book is embodied by King Charming. There’s also the ambiguity of Baker, who inadvertently contributes to wrongdoing, but also emerges as a kind of redemptive figure. What do they convey about the role of masculinity in injustice and the process of redress?

I think I wanted to take a look at the ways in which a specific type of masculinity—the more toxic type, I suppose—can be both participated in, in a sort of active, oppressive way, and then also the way one could almost be held hostage by it. I also wanted to problematise first the way that we categorise masculine and feminine and think about the assumptions we hold about those things while also asking questions about how different kinds of power can be used for a common good.

Baker has a real softness—because I wanted to subvert expectations about male heroes in fairytales—but still performs what I suppose one might call “positive masculinity,” a protectiveness, a desire to use his strength and power to help not control. But there is a temptation towards something else, something darker, a more kind of absolute power that for me explores the role that those with a voice must play in advocating for the voiceless. In the case of masculinity, I believe it is vital for men to put themselves at the forefront of fighting misogyny and this includes doing the hard work of unlearning their own behaviours. Particularly when the long history of patriarchy links masculinity so closely with the kind of superiority that is materially backed by wealth and theft and status. King Charming’s “masculinity” is inextricably linked to this. Crucially, he isn’t a huge muscled warrior—though there is a lot to be said about the way our patriarchal conditioning encourages us to body shame men—he’s an erudite politician high up in a tower because that to me is far more insidious.

Isabella Zhou