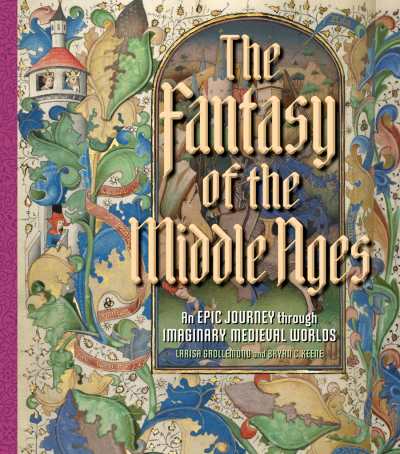

Reviewer Jeana Jorgensen Interviews Larisa Grollemond and Bryan C. Keene, Authors of The Fantasy of the Middle Ages: An Epic Journey through Imaginary Medieval Worlds

Today’s conversation, we are thrilled to discover, reveals a surprising fact about medieval society: that there was a lot more going on in terms of gender variations, sexuality, religion, ethnicity, and other realms of diversity than is commonly represented in art and literature. Indeed, contemporary folklorists are having a field day debunking the notion that the Middle Ages was lily white, Christian, and strictly heterosexual. And as these scholars sift through the stereotypes and nostalgia of medievalism—as seen in popular media from Disney films to Game of Thrones—a clearer picture emerges about how the Middle Ages continues to influence us.

Foreword recently covered The Fantasy of the Middle Ages with a review by Jeana Jorgensen, who, by the way, has a PhD in folklore. She calls the book “provocative and thorough” while making a convincing argument that “medieval-inspired stories remain relevant because their fantasies reveal modern identities.”

When we pitched the idea, Jeana jumped at the chance to connect with Larisa Grollemond and Bryan Keene, authors and folklorists extraordinaire.

Enjoy the interview!

What is your favorite little-known fact about the King Arthur legend or Arthuriana in general?

The Arthur legends have everything audiences today could want: knights of color, queer couplings, powerful women, magic, and more. We’d love for audiences today to know more about this historical diversity in Arthuriana and to not question casting decisions or plot points that may seem too modern. Not all aspects of inclusion and equity are contemporary values. We love the way creatives throughout time have personalized and updated the account for their time. In the nineteenth century, Julia Margaret Cameron incorporated friends and family members into staged photographs of major moments from Alfred, Lord Tennyson’s retelling as the Idylls of the King.

To that end, one of our favorite little-known “facts” about Arthur is that there are no facts at all! Arthur and the stories surrounding him have always told us more about the cultures in which they’re created than anything having to do with “the Middle Ages”—we are always creating the Arthur we need for the current moment.

In the book, you repeatedly make the point that the medieval times were far more diverse in terms of ethnicity, religion, and alternative genders and sexualities than commonly believed. And yet the afterlives of the medieval times in contemporary fantasy literature frequently erases that diversity. Do you think modern fantasy will catch up to the diverse lived experiences of the past, and if so, when?

We do see greater diversity in medievalisms especially in young adult literature, in Manga and anime, and in Renaissance fairs or gaming communities, such as Dungeons & Dragons. These are the fields we’ve been most interested in following because they are updating views of the Middle Ages that feel both reflective of the medieval past and relevant for audiences today.

We’ve also seen some great examples in recent films that present this diversity, but audience responses have been divided. In the genre of medievalizing fantasy—such as The Lord of the Rings, Game of Thrones, or The Wheel of Time—we find it surprising and troubling when audiences resist the presence of dwarves, elves, Aes Sedai, or rulers of color. If fantasy realms already incorporate magic, why can’t they also include a diverse cast? On the one hand, we’ve resisted the urge to fact-check fantasy medievalisms but we also recognize the importance of exposing people—museum visitors and online audiences in particular—to the vibrancy of the medieval world so they see the value in inclusive imaginings of the past.

As a folklorist myself, I really appreciated your inclusion of the Grimms’ fairy tales and other major fairy tale works as being deeply connected to ideas about medieval settings, from the gender politics of damsels in distress to the image of the knight in shining armor. Do you think fairy-tale retellings are enjoying a spike in popularity nowadays for the same reasons that medieval-inspired media are?

Yes! Fairy tales are having a moment! Like the gamut of medieval-inspired media, fairy tales afford authors opportunities to address aspects of identity in coming-of-age stories with the wondrous additions of magic. What’s not to love? Ebony Elizabeth Thomas’ The Dark Fantastic (2019) is one of the best recent studies about race and popular imagination in medievalizing tales. Karrie Fransman and Jonathan Plackett rewrote the Grimms’ fairy tales in Gender Swapped Fairy Tales (2020) with some humorous alternate endings to familiar stories. Soman Chainani’s Beasts and Beauty: Dangerous Tales (2021) adapts the tales with narratives of queer and trans inclusion. These authors have accomplished what centuries of creatives before them have done: they’ve made the Middle Ages relevant in ways that encourage us to rethink our assumptions about the past and views of the present.

In addition to the variety of texts—films, fashion, games, and more—that you explore in your book, are there ways in which the medieval ages are still influencing us that you think should be discussed more? Is the ghost of the Middle Ages still unexpectedly swaying us?

The Middle Ages really are everywhere if we consider the global markets for film, fashion, games, and more, but also the medievalizing architecture found in colonial contexts across the planet. The North American, and specifically United States, context for some of these medievalisms certainly deserves greater attention. The role that women artists and authors have played in advancing inclusive views of the medieval past is also another area we found ourselves considering more and more as the project developed.

One major arena for medievalisms that we touched on in the book is, of course, digital and social media: especially TikTok (#MedievalTikTok), Instagram (@Greedy.Peasant), Twitter (“Weird Medieval Guys” @WeirdMedieval) and other platforms are driving new kinds of engagement with the idea of the medieval and its art (open access/digital image collections are platforming medieval imagery and social media reinterprets them in all sorts of new ways). We think these are some of the most interesting, and largely unexamined so far, instances of reusing the Middle Ages today.

Is there a medieval-inspired text that simply makes you cringe? Or alternately, laugh in befuddled delight?

There’s something cringe-worthy about nearly all medieval-inspired texts and/or their creators, from Tolkien to J.K. Rowling (yikes). We did find ourselves befuddled with Disney’s The Black Cauldron (1985). In a blog post we wrote, “Every character is somehow the worst character in this extremely bizarre attempt at medieval worlding.” We did go back and re-read various Welsh, Scottish, Irish, and Scandinavian medieval legends after our start-and-stop attempts to finish the film, but we still stand by our 1 ½ castle emoji rating.

In the acknowledgements, you mention celebrating all aspects of nerd culture, a sentiment that I share, as well. What was your favorite intersection of nerd culture with medievalism to research, and why?

Bryan: For me, I love the intersection of comic book studies and medieval studies, and also video game studies and medieval studies. These medievalisms have global reach and as such tell us what the Middle Ages mean in wide-ranging cultural contexts. Overall, it’s been fruitful to reflect together on the ways we’ve experienced medievalisms at different points in our lives and careers. Being basically the same age, it’s been fun to compare and contrast the ways Larisa and I both experienced the Middle Ages from an early age and how this exposure led us to where we are today.

Larisa: I really love what comes out at Renaissance Faires—the ethos of the Faire and its flexibility to include not just medieval nerds, but everything from steampunk pirates to Stormtroopers as well, is a testament to medievalism as a practice. It’s a body-positive, inclusive place for self-expression and exploration, and seeing that develop in the 21st century against the backdrop of a medieval theatrical reenactment that takes place in an Elizabethan village is such a weird and cool phenomenon. People at the faire, like many creators of medievalisms, are continually reinventing it to suit new needs and it’s a place where the construction of the new Middle Ages is always underway.

What are you working on currently? Will there be more medievalism research in your futures?

California is ripe with medievalisms and we have some amazing colleagues here who share our interest in this work, specifically Alison Locke-Perchuk (California State University, Channel Islands) and Roland Betancourt (University of California, Irvine). We’re hoping to look closer at Indigenous responses to or acts of resistance against the medievalizing mission network. We’re also committed to getting back to the Medieval Times dinner and tournament, and participating in local Ren faires.

Some exciting future projects:

Larisa: I’m at work developing future exhibitions at the Getty, including one that explores the multifaceted topic of blood as it intersects with medieval devotional, medical, and political (among other) discourses. I’m on Twitter @LGrollemond.

Bryan: I’m co-editing the volume Balthazar: A Black African King in Medieval and Renaissance Art (Getty Publications), which will be released by February 2023. And I’m working on content for @_medievalart and @balthazar_theblackmagus on Instagram.

Jeana Jorgensen