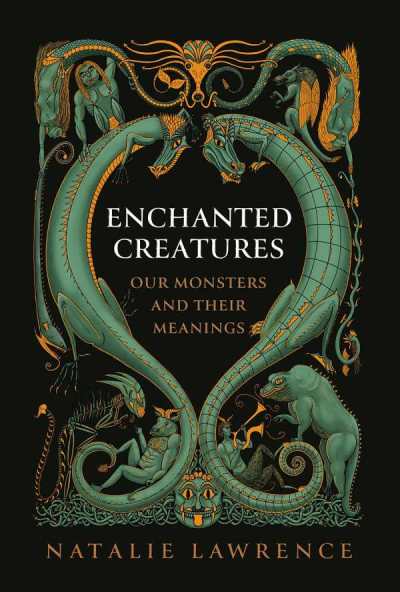

Reviewer Jeana Jorgensen Interviews Natalie Lawrence, Author of Enchanted Creatures

“Beauties have been drawn to Beasts for hundreds, if not thousands of years. They’re the ultimate bad boys: alluring but dangerous, as enjoyable and bad for you as all addictive things are.’’ —Natalie Lawrence

Of all the roles for monsters to play in our fragile psyches, all we can do is smile in admiration at the mischievous few who fantasize about a beastly Mr. Right baring their fangs and savageness during pillow talk. Sure sounds like risky behavior to us, but you go, girl.

For the vast majority of humankind, monsters have long held a darker, scarier place.

But Natalie Lawrence would like to point out that fear of monsters also serves a healthy purpose, in that it allows us to “luxuriate” in our fear safely, “enjoying all the thrills with none of the danger.” This simulated fear can be cathartic, she says, “creating defined emotional peaks, as you might get in a horror movie, that are acute and bounded.”

In today’s interview with folklorist Jeana Jorgensen, Natalie also explains what’s going on with the monster romance phenomenon, why monsters reveal the human condition so perfectly, and so much more.

So, take a peek under your bed and then learn something about yourself from the acclaimed author of Enchanted Creatures: Our Monsters and Their Meanings.

Jeana’s review of the book appeared with many dozens of other enchanting books in Foreword‘s March/April issue. Let’s not forget to mention digital subscriptions to the magazine are free.

Differences in human identities—gender, race, colonizer vs. indigenous—shape so many of the monsters in our lore. What is your favorite example of how monsters actually exemplify an “us vs. them” conflict?

As much as there are plenty of humanoid monsters that exemplify the worst aspects of our relationships to “others,” some of my favourites are the strange creatures described by early modern explorers—partly because they’re so ridiculous. Take Dutch travellers and officials in the East Indies in the seventeenth century, for example. They would quite literally interpret the natural history of the plants and animals they encountered in a way shaped by the human interactions they had there. So, in places with colonial strife, we have accounts of devilish, bulletproof pangolins that burrowed under colonial buildings, extraordinarily poisonous upas trees that would kill anything that came within ten leagues of them, and degenerate orang-outang “wildmen” who raped human women. These representations shifted with the changing colonial relations in such places—so, as antagonism and neophobia settled, the pangolins became benign little pest controllers, the upas trees became more reasonably toxic, and the lothario apes calmed down their pillaging efforts.

Two words: monster romance. How do you see this popular niche in romance novels extending the ideas in your book, perhaps making literal our fascination with monsters?

Well, if our sexuality is infused with the nature of our early psychological architecture, it makes perfect sense that monstrous figures representing these traumas, experiences, perversions, should be a big hit in people’s private-but-shared fantasylands. It’s not a new trope at all. Beauties have been drawn to Beasts for hundreds, if not thousands of years. They’re the ultimate bad boys: alluring but dangerous, as enjoyable and bad for you as all addictive things are. These monster men also often have the glimmer of possible redemption. They can be turned good, the Beast can transform into the prince he really is, redeeming his paramour at the same time.

Fear is a constant thread running throughout the book, as humans grapple with our fears of darkness, the unknown, and so on through our storytelling. How do you think we can most constructively face our fears, especially when fears going unchecked can lead to truly destructive outcomes?

Monsters play this interesting role when it comes to fear. Their horrific bodies make fear tangible, a sensory experience for the eyes and ears which invoke the somatic sensations of fear itself. They also glamourise fear, allowing us to luxuriate in it safely, enjoying all the thrills with none of the danger. These simulations can be deeply cathartic—creating defined emotional peaks, as you might get in a horror movie, that are acute and bounded. They might push deeper fears into the realm of the ridiculous—caricaturing worries so they seem grotesque, ridiculous, dismissible. They might offer fantasies of our most serious worries being defeated by heroes.

But they can also escalate fears—such as phobias of other groups, of our past, conflicts—making them all the more monstrous. There’s a reason why things “grow horns” if you let them. So, ultimately, disentangling the monsters and facing the raw fears of which they are made in a sober, clear-eyed way is going to be the only way of handling them in the long term.

In some chapters, you refer to traveling or attending events before the first wave of the Covid-19 pandemic. Would you say the collective experiences and fears of people worldwide have shifted in response to the pandemic, and if so, how?

I think Covid generated monsters in a way that we hadn’t seen for a long time. Not only did we now have a new, deadly and contagious pathogen to worry about, it also remained imperceptible until it was too late, rendering apparently healthy people potential infectious agents. This is definitely a growing trend in modern monster films and horror: infected zombies, pathogen-induced apocalypses, cordyceps monsters—representing our fears of loss of bodily and mental autonomy. Nothing is more terrifying than a monster that erupts suddenly from the body of your family member or friend, right?

Added to that, lockdown pushed us into our own minds by shutting down our external worlds, which forced many people to meet their inner monsters in ways they had previously avoided. Mental health tanked. Humans also have a tendency to become more neophobic under stressful conditions—so it’s very likely that the pandemic accentuated xenophobic and political prejudices. The effects of all of this are probably still with us.

Throughout the book, you allude to more monsters than you had room to include. What are some of your favorite beasts that remained on the editorial chopping block?

During the writing process I decided to shift towards monsters that really embody our relationship with other animals and nature, creaturely monsters as it were, rather than those on the border between human and animal. This was in the interests of clarity and focus, but also meant that some of my very favourite monsters had to go.

Top of this list of omissions may be no surprise: vampires. They’ve come to the fore recently with the release of Robert Eggers’s Nosferatu, but vampires are in some ways the perfect monsters. They play out really primal psychological processes with theatrical flair, and at the same time can fill any social commentary roles you can imagine. They can be critiques of elites, political regimes, sexuality, races, what have you. The different vampire iterations combine really gritty folkloric roots, luxuriant gothic glamour, and enviable aesthetics to differing degrees. But, while they’re really connected to beasts like bats and wolves, and beastly in many ways, I thought vampires were a bit too human to be in Enchanted Creatures.

Your concluding thoughts on dystopias are quite timely. Which lessons do you think humans must most urgently learn from our beastly brethren?

I think one message that I really wanted to convey was that the monsters are neither “out there”—beasts to be exterminated in the wilderness, nor “in here”—we are not monsters who should be eradicated. As much as many of the dystopian fantasies in the cinema or recent books might indulge these two options. Neither is going to be helpful in finding a sustainable future.

We can take inspiration from John Gardner’s Grendel, who sits alongside the likes of Shakespeare’s Caliban or Frankenstein’s Monster. All of these wildlings sit on the border between humanity and the wild. In their natural state, they’re acutely susceptible to wonder, yearning for beauty and connection. It’s only when they’re rejected, controlled, and driven away that they become monstrous. They reveal the human condition so clearly: our humanity dies without connection to each other and to nature.

Jeana Jorgensen