Reviewer Jeff Fleischer Interviews Christophe Lebold, Author of Leonard Cohen

“Cohen was fundamentally an alchemist: someone who transforms matter, takes what is darkest and heaviest in life (melancholy, death, depression, desire) and turns it into pure light. What he basically taught is that we can all become alchemists of our own lives. His message? Travel light, play with the gravity, offer yourself to love. That’s how you become a messenger of grace, an angel.’’ —Christophe Lebold

Today, we’re celebrating an artist who created masterpieces in the ethereal place where music meets poetry. We stand in awe of those top level poets—and genius musicians—who somehow combine the two distinct art forms into, what certainly is, the most beloved expression of beauty and entertainment of all.

Born in 1934, Canadian Leonard Cohen came to songwriting and performing midlife, after publishing several collections of poetry and two novels. He quickly made a splash in New York’s folk scene in the late 1960s with musicians like James Taylor covering his songs. Bob Dylan called him the number one songwriter of their time. It’s difficult to overstate his influence on music and poetry even today.

Dazzled by Jeff Fleischer’s praise of Leonard Cohen: The Man Who Saw the Angels Fall in his starred review for Foreword’s September/October issue, we quickly connected him with Christophe Lebold for the following conversation.

The Man Who Saw the Angels Fall would bring a smile to anyone on your gift list, and here’s five more special projects from the Gift Ideas spread in that September/October issue.

Register for your free digital subscription here.

What was the specific inspiration for you to write the book?

When I discovered Leonard’s work, his universe (where people step into avalanches, fall in love with fire, and find salvation in hotel rooms) seemed an exact, precise portrayal of my inner life: it was absolute realism. I felt such a calling that I couldn’t leave Leonard’s work alone. Leonard Cohen had ignited a fire inside me and given me an itch, an urge to “write back.”

Plus, I believe in the power of language. When used well, language clarifies things: it brings light. I needed to clarify what it was in Leonard Cohen’s art and life that touched me so much, and the PhD I had written on his songs was only scratching the surface. The Man Who Saw the Angels Fall is the result of that attempt at writing as an act of clarification.

What was your personal introduction to Leonard Cohen’s music?

In secondary school, in my third or fourth year of studying English—I was about fifteen—my father took out of his closet two LPs he had bought the year I was born: New Skin for the Old Ceremony and Greatest Hits. I felt an incredible hospitality in those songs: I loved the rolling arpeggios and haunting melody of “The Stranger Song” and it seemed like the quiet, delicate voice I heard was coming from deep inside me and delivering important metaphysical information. Around the same time, I was intrigued by a video I saw on TV, in which a cool guy with a black coat and a gravelly voice was singing his plans to take Manhattan and Berlin in front of the sea. I was fascinated to see it was the same guy.

The book does a great job of telling Cohen’s life story as a kind of odyssey marked by influential episodes along the way. How did you go about organizing the book when you started the writing process?

There were two incentives. Obviously, as a biographer, you have to get the facts right (which in itself takes years of research) but, beyond the facts, I wanted to engage with the deeper dynamics of Cohen’s life, the callings that drove him, and the conflicts that transformed his life into a perfect novel: the pursuit of love in all its forms, the struggle with the abyss of depression, his game of hide-and-seek with God, the dialogue with the logos, and the cosmopolitan urge that drove him from Montreal to New York and LA via a Greek island, monasteries, and a thousand hotel rooms.

The second incentive is that I wanted to deal with Leonard Cohen’s complete works, but each analytical stop (on a specific book or album) had to be a little piece of metaphysical investigation: What concepts would crack its code? How did it fit in in Leonard’s overall emotional and spiritual trajectory? I wanted the book to be a kind of metaphysical thriller with suspense and drama—about the fall of man, the art of seeing angels, and the mystery of being Leonard Cohen.

What most surprised you in the research process? What did you learn about Leonard Cohen that you hadn’t considered before?

First, how incredibly deep and cohesive the work is. Like a Greek philosopher, Leonard Cohen uses his songs to investigate the human condition and the laws of the world: the law of gravity that makes us fall, the law of attractions of bodies that makes us love, and the law of constant gravitation that keeps each of us on a specific journey.

When I consulted his private notebooks and diaries in 2015—scorching material—I was also surprised to see the extent to which, despite enormous resilience and a strong sense of humor, the singer had spent a great deal of his adult life in the flames of desire and in the black fire of depression. He once said that poetry was just the ashes of a life that was burning well and that the heart sizzles like shish kebab on the furnace of love. And indeed, he himself was burning constantly and his song “Joan of Arc” is probably (among other things) one of his finest self-portraits. But the flames in question were also the purifying flames of purgatory that finally transformed him into a creature of pure light, a teacher who points the way to awakening.

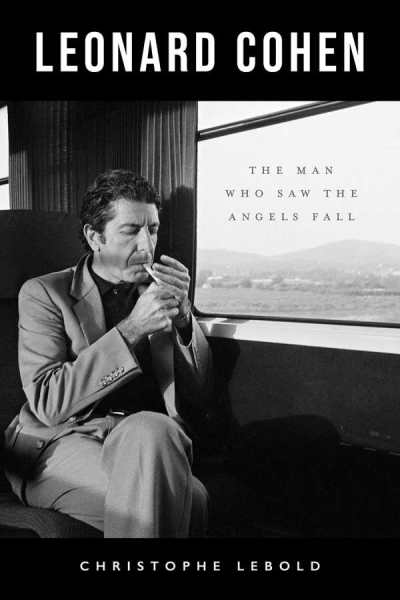

At some point, he had defined an ideal he called “the smokey life,” a life without attachment that had the texture of smoke and was a constant holocaust of offering to heaven. That’s why we chose for the cover that wonderful picture by Dominique Issermann of him smoking a cigarette on a train: an ontological stranger, at ease with the fact that he’s consuming, and ready to ignite the world (and our souls) with his spiritual vision.

How did your own experiences meeting Leonard Cohen influence your approach to researching and writing the book?

As I was first writing the book, I occasionally sent him outlines or titles and he always gave his encouragements. I had sent him my PhD a few years earlier. Later, when the first French version of the book was published, he offered me a medal with his signature sign of the intertwined hearts and the benediction of the kohen. When we finally got to spend time together in LA, we were already talking like old buddies (and little buddhas), but he also insisted that we were colleagues: two writers in a room, talking shop.

Beside his almost otherworldly perceptiveness and intelligence, I was struck by his sense of humor and his incredibly warm and loving presence. He was like a powerful archangel at this stage and a fascinating man to hang out with. To a certain degree, his mere presence was a teaching on how to live your life from moment to moment.

Do you have a favorite era of Cohen’s work? (Or a favorite album or song?) If so, what does that specific material say about him to you?

I like all periods: each is like a different moment in the saga that is Cohen’s life. I find his journey incredibly inspiring, how the different phases of his work fall into place to form the perfect novel: how the provocative poet of his youth, who looked for sainthood and celebrated sensuousness, became an existential troubadour who struggled with love and angst, and then (with the influence of zen) a warrior poet—a samurai—who embraced opposites and led countless wars against the world, women, God, and himself, before, eventually, becoming an ironic crooner and a spiritual figure: the fedora bodhisattva, who taught his audience the way of enlightenment.

Musically, my personal preferences go to Ten New Songs—a study of the phenomenology of spiritual awakening in the form of cool electro-pop songs (like “Boogie Street” or “Here it Is”) to Recent Songs and Old Ideas, both of them incredible records (with songs like “The Guests” or “Going Home”). Of course, I adore the wonderful first album (with “Stranger Song” or “Master Song”) and its companion piece, the novel Beautiful Losers.

What do you most hope the audience comes away with after reading Leonard Cohen?

Nobody needs a book to enjoy Leonard Cohen’s work, but maybe The Man Who Saw the Angels Fall can be of use to fans—casual or hardcore—who might want to deepen the conversation with Leonard’s life and work.

If anything, the book tries to point to the many ways in which, together with being a great poet, Cohen was fundamentally an alchemist: someone who transforms matter, takes what is darkest and heaviest in life (melancholy, death, depression, desire) and turns it into pure light. What he basically taught is that we can all become alchemists of our own lives. His message? Travel light, play with the gravity, offer yourself to love. That’s how you become a messenger of grace, an angel.

But regardless of that, I hope people enjoy the book as a book. I love the cover, the abundant iconography, and ECW’s elegant design. I also love the pace of narrative, how the book is divided into chapters and then into small, readable, titled sections. I worked hard to make concepts rock and the prose swing, and I hope people will enjoy that. But you never know. Like Leonard said in a famous song: “I did my best, it wasn’t much.”

Jeff Fleischer