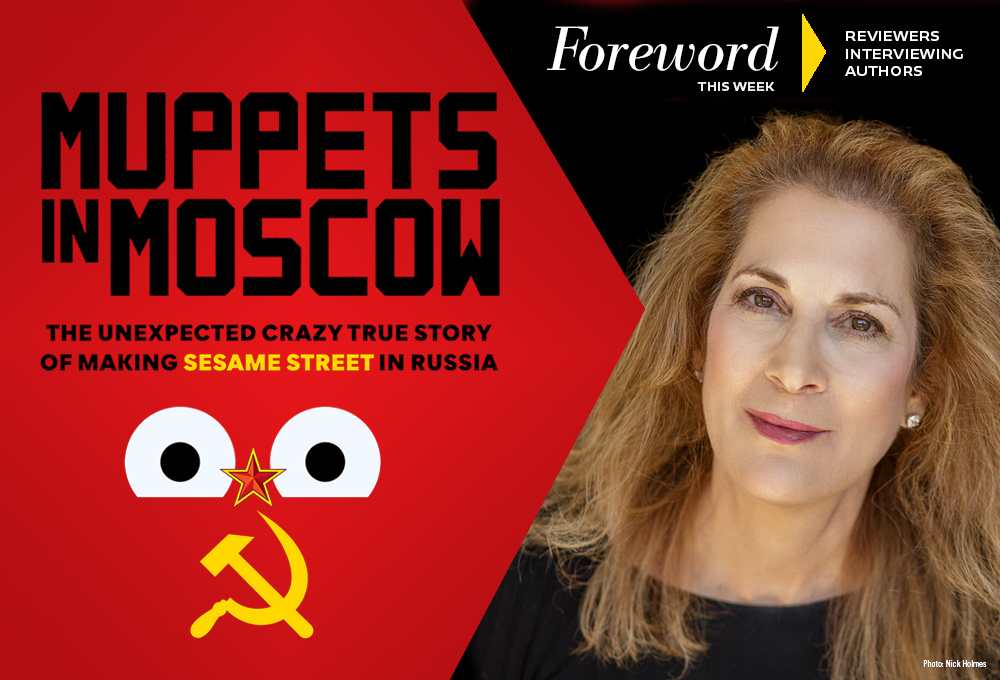

Reviewer Jeff Fleischer Interviews Natasha Lance Rogoff, Author of Muppets in Moscow

Muppets in Moscow. You might think the title of this week’s featured book is a mocking reference to Russia’s bumbling military leadership because Putin’s team seems to have the same level of prowess as Miss Piggy, Kermit, Gonzo, and the gang as it seeks to occupy Ukraine.

But no, in the interview today, you’re actually going to hear how our guest, Natasha Lance Rogoff, adapted Sesame Street and made it a hit on Russian television. But Natasha’s story is almost too incredible to believe.

In the interview below, she tells of building a crew of more than four hundred Moscow actors, musicians, writers, and set designers—even as several of her broadcast partners and friends were gunned down in the battles to control Russia’s top TV station. Oh, and then there’s her story of Russian soldiers with AK-47s seizing Elmo as they took over her puppet production office. (Not surprisingly, her husband begged her to quit after that episode.)

Jeff Fleischer reviewed Muppets in Moscow for Foreword’s September/October 2022 issue, and with the help of the good people at Rowman & Littlefield, we put reviewer and author together for the following chat.

For readers who haven’t seen the book yet, how did you go from making a documentary about Russia to working on bringing Sesame Street to the country?

I went to the Soviet Union for the first time as an American exchange student in the 1980s to study Russian. While there I began writing about underground culture—about the persecuted LGBTQ community and underground rock musicians who were officially banned from recording their music or performing by the Soviet regime. I also began filming with a friend and my short film Rock Around the Kremlin aired on ABC’s 20/20 program. In 1992, the documentary I directed, wrote, and produced that predicted the collapse of the Soviet Union, aired on PBS and also on ABC’s Nightline with Ted Koppel.

At a New York screening, two executives from Sesame Street approached me and asked if I could help them adapt American’s favorite children’s educational show in Russia. I nearly froze, wondering what in my ultra-dark PBS documentary could possibly have made them believe I could lead the production of an educational children’s comedy program. But it turned out the idea wasn’t so crazy. Some of my once-banned underground rock friends, for example, had suddenly become huge stars familiar to young parents across the former USSR, and I was able to persuade my music friends to contribute to Ulitsa Sezam; and some of the songs are hits to this day.

Perhaps most importantly, I had an appreciation of the incredible artistic talent in Moscow at the time—passionate, creative people whose fresh ideas were too radical for the staid state film system, or who were excluded for reasons of identity. By the way, we ultimately hired talent representing nationalities from across the former Soviet Union: Ukraine, Georgia, Armenia, Kazakhstan, Moldova, etc.

Muppets in Moscow really shows how many obstacles you had to overcome just to get buy-in for a Russian version of Sesame Street. Knowing some of those challenges in advance, which most surprised you?

Despite having spent nearly a decade living and working in Russia, I grossly underestimated the challenges involved in adapting the light-hearted American children’s comedy show in Russia. I was young, thought I knew everything about Russia, and thought I understood the risks and challenges; I knew nothing. First, there was the unremittent violence: as the book recounts, our Russian Sesame Street broadcast partners—who in each case had become my friends—were assassinated one after the other as a result of internal battles to control Russia’s dominant TV station (there were only two major channels back then). Our puppet production office was taken over by Russian soldiers with AK-47s, who literally seized Elmo. It is a miracle the whole team didn’t quit after that; my husband, back in the States, certainly wanted me to quit after all that

But in some ways, the biggest battles were inside the production itself. Russians are proud people with a storied cultural heritage including Dostoevsky, Tchaikovsky, and Kandinsky. Some chafed at the idea that anything remotely resembling the American show could work in Russia. Every aspect of the production involved heated debates about what Russian children needed to learn in order to thrive in their new democratic country. My Slavic colleagues rejected Muppet-style puppets at first. The show’s Russian head writer asserted that their country has a long, rich, and revered puppet tradition dating back to the sixteenth century and said, “We don’t need your Moppets.”

Other battles involved divergent beliefs and values about diversity, capitalism, equality, gender rights, and race. For example, there is a chapter in the book about how my Russian colleagues did not want to include any disabled “Nenormal’nye” (not normal) children. A few insisted that portraying a young child running a lemonade stand (to teach math and model what a market is) would glorify capitalist criminals who sell goods on Moscow’s streets. But they also came up with ingenious ideas and their artistic capabilities exceeded even my high expectations. For example, the lead Russian Muppet, called “Zeliboba,” is a furry blue tree spirit. We all learned the importance of communicating and trying to understand each other’s perspectives, and I think it was this creative tension that made Ulitsa Sezam so extraordinary.

On the other hand, you talk about working with many talented Russian artists. What do you see as the biggest successes in developing a Russian voice for the show?

The goal in adapting Sesame Street to Russia was to create a TV series that would reflect the culture and values of post-Soviet society. I led a team of over four hundred Moscow artists, musicians, writers, actors, set designers, and TV professionals and our shared priority was to create a TV series that would be distinctly Russian (really, Slavic) and also relevant to the millions of children who were living across the former Soviet Union, including Ukraine, where Russian was predominantly spoken. Our team was extremely talented and committed to modeling a freer, more open, and kinder neighborhood society for children to experience—first on television, and then hopefully in reality.

To accomplish this, our stateside Sesame Street colleagues recommended that the new Russian set reflect a familiar reality for Russian children. The Russian creators proposed that the show’s neighborhood set be constructed as a traditional Russian courtyard surrounded by buildings on four sides. In Soviet times, the courtyard was supposed to be place where dentists, doctors, and laborers would interact, supposedly removing class barriers between neighbors. But one education expert objected—arguing that if Ulitsa Sezam was truly supposed to reflect reality, then the courtyard should have a rusty old car and shards of glass and include residents who report on their neighbors to the KGB. The final set is just magical, even if at times it seemed that we had to move mountains to get just the right elements to correspond to what the Russian set designers envisioned. For example, this included a four-month search for the “right” type of Russian oak leaf with six points.

When did you feel confident the show was going to make it to air after so many close calls?

To be honest, you have to read the very last chapter, and indeed the very last scene in the book to get a truly honest answer to this question. It is a very moving moment for me; I still cry sometimes when I think about it. Anyone who has lived and worked in Russia will understand, you cannot rely on anything when it comes to the state. But once just one episode had aired, the show became such a sensation that even Putin, when he came to power four years later, breathing nationalistic fire, couldn’t pull this American-inspired—but still very Russian—show from the air. It remained a hit for almost a decade, playing in prime time and on Russia’s top two television channels several nights a week.

Looking back, what impact do you think the show had on its Russian audience?

Every time I returned to Russia, after Putin came to power, I would encounter young adults who had grown up on Ulitsa Sezam. When I told them I had been a part of its creation, they treated me like their favorite celebrity and gushed about how much they love the Russian Muppets, Zeliboba, Kubik, and Businka. They would start singing Washing Hands, the hit song composed by my old rocker friend who later became Russia’s so-called Mick Jagger. They often spoke about how they had never seen anything like our show—a place where children felt free to play, experiment, and make mistakes without being afraid. They spoke about how the show had influenced their own lives—imagining a world where people treated each other more gently and children were encouraged to hope that they could achieve anything they could imagine. This is Ulitsa Sezam’s legacy.

What do you most hope the audience comes away with after reading Muppets in Moscow?

I hope readers of Muppets in Moscow will enjoy this fast-paced, gripping story while also getting a visceral feeling for what it was like living in Moscow as an American during a time of extreme chaos and violence. Additionally, I anticipate the story of adapting Sesame Street to post-Soviet society gives readers deeper insights into the ways in which values and beliefs differ in Russia and the West. It is my belief that the recent disintegration of the West’s relations with Russia, while exacerbated by the horrific war in Ukraine, started long before. I hope the telling of this story about the Muppets in Moscow will enable readers to understand more fully how our unique cultures and values continue to impact our relations today.

Jeff Fleischer