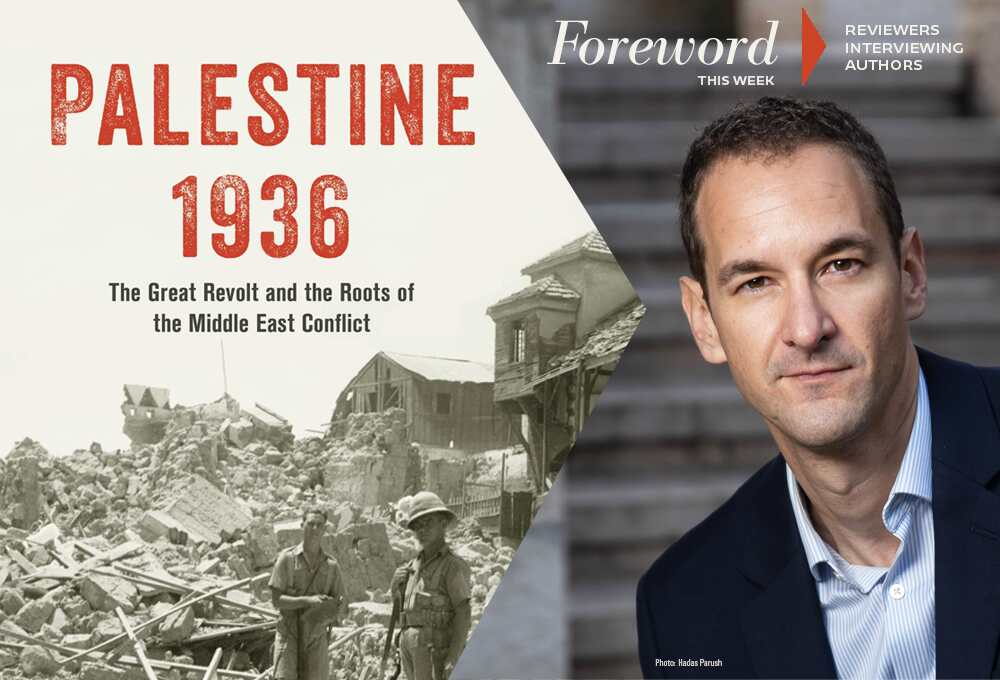

Reviewer Jeremiah Rood Interviews Oren Kessler, Author of Palestine 1936

Written history has a way of providing both comfort and confusion to readers. Just because you’ve studied a place, an event, time’s eternal march through human affairs, doesn’t necessarily mean you understand the situation better. Case in point: the conflict between Palestinians and Israelis in the Middle East. Ask a roomful of fifty Middle East historians to suggest a potential solution to the world’s #1 conundrum and you’ll get a hundred different answers.

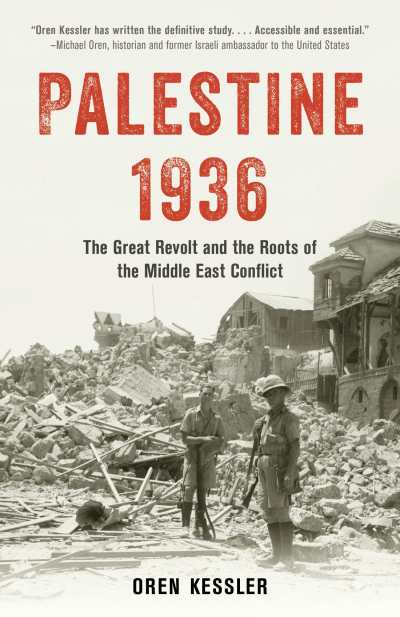

But Oren Kessler, as blue-blooded a Middle East scholar as they come, believes his Palestine 1936 does a much needed job of explaining that the origins of animosity between Middle Eastern

Arabs and Jews goes back far longer than normally imagined. Namely, to the 1930s when Palestine’s Arabs first identified a common enemy: Zionism and the British Empire for helping to birth it.

Editor-in-Chief Michelle Schingler leaned on Jeremiah Rood to review the book in Foreword’s January/February issue and we heeded her nudge to set up the following reviewer-author interview.

I really enjoyed reading the book, in part because I had this ever-present sense of hopefulness that things would work out. Let me back up a bit. The book covers The Great Revolt of 1936-39, a relatively small time frame and scale violence that becomes the “crucible in which Palestinian identity coalesced.” It pits nationalistic Arabs against Zionistic-minded Jews in a struggle over both land and power, a conflict that echoes all these years later. What do you hope people better understood about the history of the conflict?

I hope this book can illuminate a forgotten but hugely formative chapter in Israeli and Palestinian history, and of the Middle East conflict itself. I argue that many facets of that conflict’s “template” took shape not in 1967, when Israel took control of the West Bank and Gaza, nor even in 1948, when the Jewish state was born, but a decade before. It was then that Palestine’s Arabs first united in concerted action against a common foe: Zionism and its midwife the British Empire. It was then that Palestine’s Jewish community became a force to be reckoned with militarily, economically, and demographically. And it was then that momentous concepts like “Jewish state” and “two-state solution” first appeared on the diplomatic agenda.

I won’t be so bold as to claim that learning about this period will magically solve the Middle East dispute, but I do argue that it fills some crucial historical gaps in understanding how we’ve reached this point of apparently endless discord and hopelessness.

You begin Palestine 1936 by calling the events your book describes “the story—of Palestine’s first Arab rebellion, a seminal, three-year uprising a decade before Israel’s birth that cast the mold for the Jewish-Arab encounter ever since” as being the “forgotten uprising.” And, to be honest, it was completely new to me. I’d never really considered the deep historical roots of the current crisis. Can you tell us what inspired you to delve into this history?

For years I had dreamed about writing a book, and for some strange reason I decided the world needed another book on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict! That led to the immediate realization that this is an incredibly saturated field, that everything had seemingly already been written. But then I lit upon the subject of the revolt and the repercussions thereof, which I quickly recognized was a subject that was at once seminal and decisive but also seriously under-explored. And that it was a period that was filled with compelling, complex characters making history.

Some are familiar to us—people like David Ben-Gurion, Grand Mufti Hajj Amin al-Husseini, and Winston Churchill—but many others are forgotten and I believe were ripe to be rescued from obscurity.

There are a lot of moving parts in Palestine 1936, with names that may have been household names in England, but now have faded a bit into history. If you had to pick your favorite historical figure, that best shows the challenge of this time, who might you pick?

Among the Jews I would choose Chaim Weizmann, the face and muscle of world Zionism for three decades until Israel’s founding. He was an extraordinarily charismatic man who managed to charm virtually every important Briton he met. But when Britain—amid carnage in Palestine and looming war in Europe—began to renege on its commitment to Zionism, he proved utterly unable to reconcile his fealty to the Crown with his own Zionist convictions.

On the Arab side I would choose Musa Alami, a marginal or liminal figure torn between his own British ties (he was perhaps the first Palestinian Arab to attend Cambridge) and his fidelity to Arab nationalism. He also had many Jewish friends and colleagues, including Ben-Gurion, with whom despite their diametrically opposed national aims he enjoyed warm mutual respect.

You explain the various political maneuverings. The fascinating part for me was reading that it wasn’t Americans meddling in the region, but the powerhouse of the time, Great Britain. I know more about American history than British, meaning it was easier to have more psychic distance with the text, as I didn’t know who would come out on top. I’m wondering how having a British angle impacted this story. Was it easy to access the materials you needed or people to talk to?

Unfortunately, when you are writing about events from eight decades ago, there aren’t many people to talk to. I did speak with some descendants of people involved—for example, the grandson of the revolt’s first Jewish victim, an aging chicken seller recently arrived from Greece. But mostly I talked to people who were, as it were, speaking from beyond the grave. Fortunately, the British—and the Zionists—were copious record-keepers, and most of their documents are still available in British or Israeli archives. Arab sources were harder to come by—there is, of course, no Palestinian state archive—but there are memoirs and diaries in Arabic and English.

Now, this is a big ask, but I’m wondering if you have any insight into what can be done to help the region today? Or, I’m rather suspecting, that ongoing conflict is sort of baked into the region at this point. Did your work on this project leave you with the hope that a peaceful solution is possible, and if so, what do you think that might look like?

I argue that for both Israelis and Palestinians, the revolt never quite ended but makes itself felt in various ways, both visible and invisible. As just one example, in the latest brief Israel-Gaza war, in 2021, one far-right Israeli lawmaker (Bezalel Smotrich, recently named to the new Cabinet) raged on Twitter that Israel was proving dangerously lax in quashing terrorism, just like the British army during the revolt. And when Palestinians staged a one-day general strike, Arab social media was abuzz with comparisons to the six-month general strike of 1936.

But no, I can’t say this project has filled me with optimism—if anything, it was stunning how many of today’s basic bones of contention are the same ones as back then. For example, hovering above everything, then and now, is the demographic question—with each side determined to either achieve or protect a demographic majority, preferably an overwhelming one. Hence the 1937 proposal to partition the land (a two-state solution, as it were), which raised a whole host of its own complications and was ultimately put on the backburner (sound familiar?). So no, “hopeful” might not be the first word that comes to mind, sadly.

We’ve covered a lot of ground so far, but I’m wondering if there is anything you might like to talk about that I didn’t mention. I always imagine that authors are secretly hoping that someone will ask them something. Any final thoughts?

Only that this is a story as consequential to Israelis as to Palestinians and will—I hope—speak to anyone else interested in the origin of one of the world’s most intractable and emotionally charged conflicts. And that I’ve tried to be as balanced as possible, letting all sides speak while trying to stay as true as I could to the archival sources as I found them. And that history matters, particularly in this corner of the world. That for Palestinians as much as Israelis, the revolt rages on.

Jeremiah Rood