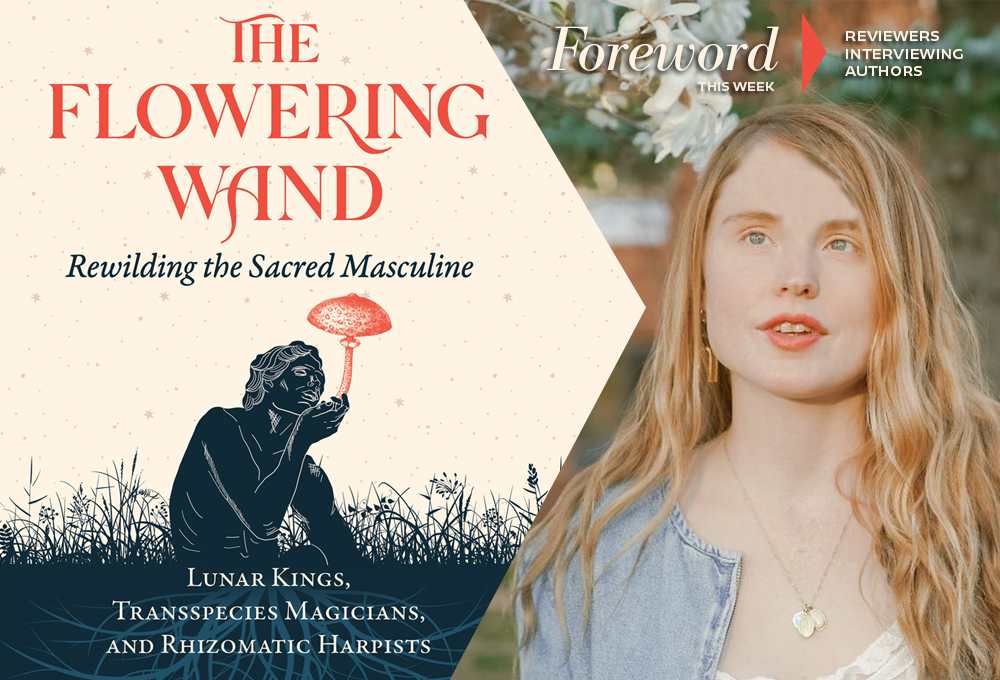

Reviewer Jeremiah Rood Interviews Sophie Strand, Author of The Flowering Wand

Manhood is a bland, one-trick pony. In pop culture, sports, business, and most everywhere else, men are celebrated for being aggressive and ambitious, stoic and decisive—but how senseless is that?

We’re experiencing major changes and challenges in the world and it’s not because we don’t have enough Clint Eastwood-types in society. What the times are calling for, what our planet’s survival is dependent on, are more Atticus Finches—as husbands, business leaders, politicians, and friends to all.

Today’s guest is transformative. She needs to be heard. Men are craving different models to express their masculinity and Sophie Strand’s The Flowering Wand offers “vital nourishment to their hearts, bodies, and souls.”

Let’s do some groundwork first. Your book explores that masculinity is using a wealth of mythological, cultural, and scientific ideas. Can you briefly explain what masculinity is and why that matters? I want to give people a taste of where you are coming from.

While I don’t believe masculinity is a biological reality, I am interested in it as an expression that repeatedly asserts itself somewhat similarly but with key differences in its articulation across various time periods, ecosystems, and psycho-social contexts. As someone who spent years researching and writing about forgotten feminine divinities, I finally came to the conclusion that not only had the divine feminine been suppressed by dominator cultures, but so had a biodiversity of masculine expressions more attuned to collaboration with the natural world. For too long masculinity has been conflated with patriarchy. It’s important to show that the monomyth of colonial masculinity as wedded to ecocide and capitalism is not the only expression available to people who identify with the masculine.

You begin the book in a really interesting place by looking at plants, and in particular, mushrooms. I loved this part because I never knew any of the science behind the life of mushrooms. I really appreciate how you link the hidden myths that define our lives, with the natural world. Why do you think myth is so central to who we are?

For most of human history, our mythic systems were created as vessels for crucial environmental wisdom. It is easier to remember a narrative than it is to remember a list of harvesting rules or directions on how to locate a specific patch of herbs. If we look back far enough, sky gods become storm gods and then, finally, storms. Mother goddesses very quickly melt back into their original essence—matter itself. Very often, heroes and heroines represent anthropomorphized plants and animals, their romantic entanglements representative of real-world relationships between symbiotic species.

In myth, elementals are personified. Harvesting schedules are embedded in episodic family dramas. Myths, like mycorrhizal fungi, provide a map of our forest of relations. They can be a powerful way of coming back into dialogue with the webs of relation within which we find ourselves negotiating climate change and social upheaval. We cannot return to the folk traditions of our distant ancestors. But we can reclaim myth as a way of rooting back into a resilient multi-species network of beings with more feral suggestions on how to dismantle systems of oppression.

You return often to the images of the Tarot deck, finding it to be a great source of mythic inspiration. I wonder if you could speak a bit about how that happened. I almost wanted to recommend your book as a resource for Tarot practitioners, but it seemed a little too tangential. Which came first: working with the mythic or exploring the world of Tarot?

I grew up as the child of parents studying and writing about the history of religion. I listened to Egyptian myths on tape. I was read Ovid and Homer aloud as I fell asleep. I studied the history of religion in the Mediterranean basin. I also grew up in a world of more-than-human storytelling: rehabilitating wild opossums and owls, raising geese and ducks, collaborating with anarchic tomcats, playing in mushroom-constellated patches of mossy forest. Mythology always leaked past the human for me, back into its original habitat in the world of multi-species collaboration. A story was only useful if it helped me come back into dynamic conversation with my actual ecosystem.

My parents encouraged me to retell older stories with new frames: with animal characters and modern scientific information. Tarot came much later. I studied the contested history of the cards but quickly came to the conclusion that the Tarot would only be useful if I composted the meanings and literally planted each card back into the soil of a natural metaphor. I gave readings for several years using an ecological frame for each card.

I really appreciated how you go right to the heart of a central problem in western philosophy, which trusts “what we can see and prove” and thus “we can believe.” You suggest that this leads to Descartes offering humanity two things: a mind and a dead world. Then your book does something wonderful, it takes a step beyond this argument to focus instead on that “dead world” and finds it very much alive. Where does this new awareness lead humanity?

I hesitate to make any predictions about humanity’s direction. But I do think that if we are going to survive it will not be alone. It will be in symbiotic collaboration with other species and with other people. This will involve an understanding that the best thinking doesn’t happen in the atomized self. It happens in the connective tissue between different belief systems, different species, and gender expressions. If we understand that the world we inhabit is alive but alive in ways that are inherently different than our mode of conciousness, we might begin to ask questions of trees and animals and fungi that open up better futures we could never have imagined from a purely human perspective.

Jeremiah Rood