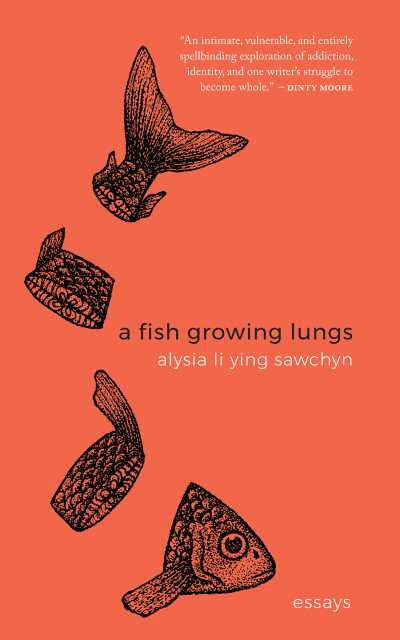

Reviewer Jessie Horness Interviews Alysia Li Ying Sawchyn, Author of A Fish Growing Lungs

Strutting around the planet as the most evolved of all creatures, you wouldn’t think that being human would be as hard as it is.

Yet, for all of our intelligence, every one of us will struggle with mental and physical adversity at some point in our lives, not to speak of the angst caused by simply taking note of all the suffering going on around us. Our number one position on the food chain isn’t all that it’s cracked up to be, and the carefree lives of otters and songbirds seems a lot more attractive by comparison. It hurts to be human.

This week, our guest is Alysia Li Ying Sawchyn, the author of a powerful collection of essays on her own struggles with cocaine addiction, mental illness, and diagnosis. In her review of A Fish Growing Lungs for Foreword Reviews, Jessie Horness writes that Alysia provides a “behind-the-scenes peek into the lack of objectivity of the [mental health] system,” and that this “unveiling … is empowering stuff.” She ends the review by saying the book “invites a conversation about how we approach human suffering,” so we offered Jessie a chance to do just that.

Jessie, the stage is yours.

Thank you so much for agreeing to answer a few questions! First, I’d like to express deep appreciation for your book. In much of my work I see folks who enter my office with a laundry list of previous diagnoses. This work is a gift to conversation around loosening the power of those labels.

Each of these stories comes in for a new strategy—not in the form of gimmicks, but as if you’re purposefully trying new lenses or taking new angles in order show things clearly. How do you approach experimenting with narrative frameworks?

Lenses and angles are the perfect words for what I wanted to do with A Fish Growing Lungs (Fish). I like to think of my book as looking through a kaleidoscope. I listened to Jennifer Egan give a talk while I was in the early stages of drafting, and she spoke about using overarching metaphors to structure A Visit From the Goon Squad. Her metaphor/organizational principle for that book was a mixtape. The idea resonated with me—I love having something concrete to hold onto—hence the kaleidoscope.

For the most part, I always knew I wanted this book to avoid traditional chronology. Part of that is because of the complicated/intertwining nature of the subject matter; all of these “symptoms” added together looked like bipolar disorder, but taken separately … ? As I got deeper into the writing process, it became more methodical—I had the food essay, the relationships essay, the cutting essay, etc.

In terms of how each essay ended up with its particular shape, that was mostly a process of trial-and-error. I was in a braided essay period at the time, and it seemed like the first draft of everything I wrote came out in a plait. My brain was just wired that way for a year or two. So the early drafts would be braided and I’d have to put them away for months and then take them back out to see which strands were actually interesting and needing to be developed.

“Deep-sea Creatures” was a stand out story for me. I’m used to hearing critique and debate around the DSM-5 in professional circles, but there is something empowering about seeing the cracks in the foundations pointed out for non-practitioners. I’m curious to hear more about your process of inquiring into the “authority” of the diagnostic manual.

That was one of my braided babies that got to keep its original shape! Back in 2013, when the DSM-5 update happened, I was already doing academic work in rhetoric and composition on the subject of mental health in public spaces; the disappearance of Asperger’s was a big topic at some conferences I attended, and I’d already worked in K-12 schools doing some special ed. teaching. So the notion of the “authority” being man-made was just there. It was impossible to not see. Many disability scholars discuss the troubles and benefits of narrative in medicine and where legitimacy comes from, and I already had all that background before I started my own creative work.

All that said, it was much easier to suggest the unpacking of authority to an experience that wasn’t mine. It was one thing to write a thesis that advocated, in the abstract, for more agency for mental health patients, and another to have that agency myself. The section that I reference in “Deep-Sea Creatures” was particularly instrumental in my understanding of the DSM as a made document—it goes through a drafting process just like every other text. I think it was also easier for me because what I’m talking about in that section is a very concrete action, as opposed to say, anxiety or eating, which can feel (at least for me) a lot more uncertain. Like, “Am I not eating because I’m actually not hungry or am I not eating because I hate myself?” is much harder to answer than “Did I cut myself?” “Wellness” is much easier to understand in this way and having that allowed me to then move further into the exploring what wellness can look like for more abstract or slippery concepts.

In “Unsent,” you speak about how writing is exposure to the self of things we may not know or want to know. Would you speak a little about the process of writing a work that draws on vulnerable specificity to such great effect?

Ah, vulnerability. It’s much harder for me to admit directly to someone that they hurt my feelings than it is for me to publish a book that says I did a lot of cocaine and was in a psych ward. I think this is because I still wish to seem invulnerable and because I no longer feel burdened by those parts of my past. I’ve been in recovery for a while now, and part of that means I have a deeply-held belief in the possibility of change. In that way, I am a great optimist. This isn’t to say that there aren’t things I’ve done that I deeply regret, but this is to say that there’s still a lot of stigma around drug use and mental health issues that is pure garbage and I’m able to talk about it as such. Part of this, though, is that I’m no longer doing cocaine or on the precipice of a nervous breakdown. If I were still in that position, I might feel differently.

I am an inconsistent journal-keeper, and I also had copies of most of my old medical records from rehab and my first post-psych-ward psychiatrist. These were very difficult to read at first. It’s one thing to think, “Oh, yeah, I was a real asshole back then,” and another to read a medical professional’s opinion on how awful I was. I’d get a few pages in and then run outside my apartment, cry, and smoke like three cigarettes in a row and then shove the papers back in a box for a month. This happened maybe three times. And then finally I was so sick of myself feeling bad about myself that I just toughed it out on my porch with a pack of cigarettes. In retrospect, it was pretty gross.

At the end of “Go Ask Alice,” you speak about the role of the artist. What do you consider your role as an artist in creating this particular work?

Very generally, I think art is about noticing and paying attention, and then making something that gets other people to do the same. The process of writing Fish was about the grey spaces between the (false) dichotomies of sickness/illness/diagnoses and wellness/health/misdiagnoses. I always feel compelled to say that I don’t want Fish to be an anti-medication book or an anti-doctor book. Some meds are great and some doctors are great. But neither medicine as an institution nor medical practitioners are omnipotent, and this is compounded by issues of race, gender, class, etc. And by “issues of,” I really mean racism, sexism, classism.

What are your hopes for this book? Whose hands are you hoping it lands in?

Honestly, I’m still in shock about the fact that I have a book published in the world. I feel like it’s not very professional or poised to say that, but it’s true. The whole experience has been surreal, from start to finish, and it’s probably (now) being exacerbated by the pandemic. I’ve been asking people who have copies of my book to take pictures of it outside wherever they are and send them to me. I’m making a small collection, since we’re all stuck inside. Anybody’s hands and everybody’s hands.

Jessie Horness