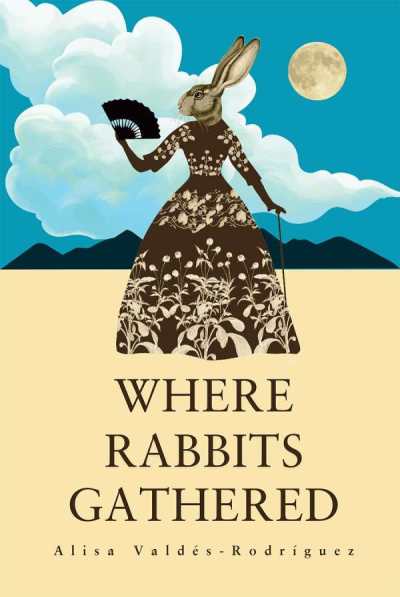

Reviewer Karen Rigby Interviews Alisa Valdés-Rodríguez, Author of Where Rabbits Gathered

Much of the novel is a powerful matrilineal history. Was there a particular moment that inspired you to explore women’s lives in a generational form?

I decided to write this book after seeing a preview of the film Oppenheimer in the New York Times, where the writer referred to the land where Los Alamos National Labs was built as empty and desolate, devoid of people. It infuriated me because Los Alamos was built on land inhabited for centuries by Spanish farmers and for thousands of years by Puebloan people. Los Alamos is near the famed cliff dwellings of the Pajarito Plateau.

When Oppenheimer built the labs, the US government literally threw dozens of Hispano and Indigenous families off land they’d lived on for far longer than the US had even existed. This history is erased in the narrative of that film, and people believe what they see in films like that. Those lies become our collective truth.* *My own family on my mother’s side were among those first Indigenous people and those first Spanish invaders. I decided to set the record straight with historical fiction based on my own family tree and history.

*Where Rabbits Gathered is the first of four volumes in the epic family saga I created, inspired by my literal family tree. I felt that the heroic male nuclear bomb maker story needed the counterbalance of the heroic peaceful matrilineal Puebloan worldview it displaces, a far superior worldview which focuses on creation instead of destruction—living in balance with nature rather than trying to play God and destroy the very planet that gave us life. *As I began researching the region’s history and its native culture, the characters presented themselves to me fully formed, like ghosts. I feel this book was guided by spirits in my bones that have been waiting a long time to speak.

History speaks to the present, if we’re willing to listen. Why this story, now? What might we reflect on from New Mexico’s past?

We have so much we can learn from history. In the case of Where Rabbits Gathered, we are talking about the horrors of genocide and forced conversions led by Juan de Oñate in 1598 on behalf of Spain against the Puebloan and other Indigenous peoples, whom he and his kind dehumanized. As I wrote this book, I saw shocking parallels to events we face today with rising Christofascism in the United States.

Oñate was not just a product of the Spanish Inquisition, he was the Elon Musk of the 16th and 17th centuries—the subpar, narcissistic son of a wealthy man who built his fortune on slave labor in silver mines. Like Musk, Oñate grew up rich and was essentially useless. He was obsessed with proving himself the greatest man alive as a psychological coping mechanism for the pure inadequacy he felt when compared to his own father. When Juan named New Mexico in 1598, it wasn’t after the modern nation of Mexico but after the Aztec Mexica empire conquered by Hernán Cortés—because he was obsessed with surpassing Cortés. Oñate, like Musk and Trump both, embodies criminality, arrogance, violence, patriarchy, and religious justification for their most violent actions against women and Othered peoples. Juan, too, dismantled societies far more spiritually and ecologically advanced than his own limited intellect allowed him to comprehend.

Today, with figures like Trump and Musk rising, we see similar themes of patriarchal power, misogyny, racism, and Christofascism. The chilling difference is that Oñate’s brutality was punished by the Spanish crown, whereas there is no one to hold Musk and Trump accountable.

Women’s relationships are shaped by many forces, and here, joy and endurance play large roles. Where in the course of writing their stories did you find the most surprise or heartbreak?

I was most surprised by the strategy of endurance through becoming silent, unmoving, secretive, invisible. In dominant US society, battles are portrayed as necessarily violent, but the Puebloan peoples I write about, the Santa Clara people of Puye, are still here in 2025. It’s a feminine form of endurance. Silent subversion. Their spirituality and culture survived Spain, Mexico, and the US through self-isolation and quiet resistance. They wove Indigenous customs into Hispanic culture so thoroughly that the conqueror and the conquered became nearly indistinguishable. This is a slow story—a story of long-term survival carried by each new daughter over four centuries.

The story that surpised me the most was the heartbreaking tale of Butterfly—a Tewa girl separated from her mother and raised in a Hopi community that adopts her, reflects this. Despite being raised as Hopi, she is never fully accepted as Hopi because of their matrilineal society and her Tewa mother. Her own brother, meanwhile, is fully accepted so long as he marries a Hopi girl, because their children will be Hopi. Butterfly’s never will. Heartbroken, she runs away and embraces Christianity for its promise of belonging through baptism rather than birth. I wanted to show the limitations of all extremely rigid gender-based systems.

The rabbit necklace is a talismanic heirloom, and it’s incredible that it lasts through centuries. Tell us more about this and any other objects. What draws you—or the characters—to them?

The necklace, made of turquoise stone, persists across centuries. It symbolizes the Indigenous heart of New Mexican culture—beating and eternal, like the land itself. Rabbits represent fertility and innocence in Puebloan culture, but they are also prey. The name of the cliff dwelling city where the book begins is Puye, which means “where rabbits gathered” in Tewa. The survival of rabbits, of women, of conquered peoples, often lies in invisibility, stillness, and the endurance of observing while unobserved. It’s not always the predator who survives; sometimes, it is the prey. In today’s United States, few understand the immense power of quiet, subversive, clever, unseen resistance—the kind that can eventually topple empires without them even noticing.

For later women in the novel, questions of assimilating, living among the Spanish, and in-between worlds arise. How do you depict this tension in a way that is both truthful and delicate, when it can feel, perhaps, like love and betrayal at once?

I wanted to show assimilation as a slow seep—not a one-way street. Conquered peoples creatively preserve themselves, blending survival with resistance. In New Mexico, the early initial fusion of Spanish and Indigenous cultures was traumatic and terrible, yet today has evolved into something quite beautiful. I avoided simplistic good-versus-evil narratives at every level, because that lens is Western and rooted in JudeoChristianity. The Puebloan way is far more loving. It embraces differences, compassionately incorporating others’ beliefs rather than demanding conformity. This book is rooted in that loving, compassionate, matriarchal worldview, a worldview concerned with peaceful coexistence and harmonious balance with nature, and unconcerned with domination and control or with people being the center of all things. I wrote with empathy for how people then understood their world compared to how we view it now. I don’t think there have been any two cultures throughout history who were so completely different from one another as the Spanish Inquisition and the matriarchal Puebloan people of New Mexico.

At Foreword we champion indie lit, and are very excited about your new press. Would you speak about the hopes behind its creation?

I created Tomé Hill Press to have the freedom to write the kinds of books I want to write—books I know will resonate with readers in New Mexico and Indigenous and US Hispano/Latino communities. New York publishing didn’t understand these stories. I was tired of having to educate agents and editors who’d never been anywhere but Brooklyn about the American Southwest and why it matters. The pure late-stage capitalism of Big Five publishing these days also leaves little room for quiet, important books. Publishing has changed a lot in the past twenty-five years since my first novel came out with St. Martin’s Press, and mostly not for the better for people like me. My goal is to publish my own work and, if successful, support other writers telling stories that matter. Tomé Hill Press is small, and local. It’s that quiet rabbit, hidden in the sagebrush. We are entering a time where voices like mine will be snuffed out if they are too loud.

Karen Rigby