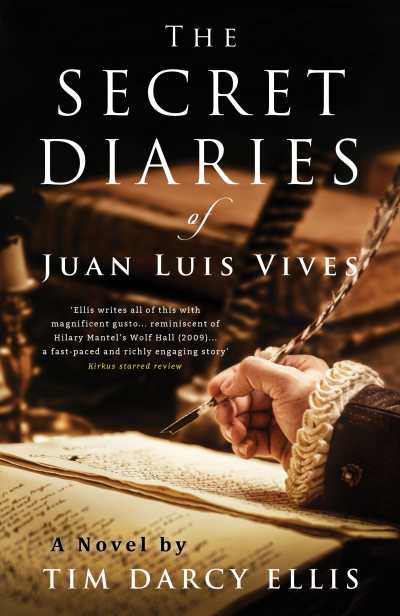

Reviewer Karen Rigby Interviews Tim Ellis, Author of The Secret Diaries of Juan Luis Vives

The lessons to be learned and excitement of history are too often obscured behind dates, places, and statistics—what’s missing is what lurks in the hearts of men (and women). History books would be so much more compelling if we knew the innermost feelings of the people who were there.

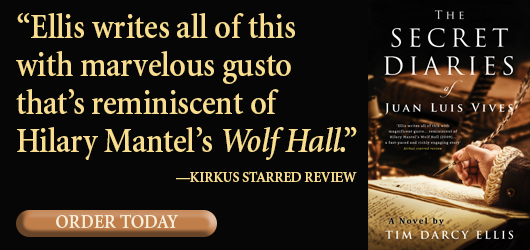

Few periods in history can compete with the intrigues of the early sixteenth century in Europe’s grand courts and palaces, with the Spanish Inquisition in full terror mode, and names like Henry VIII, Thomas More, Anne Boleyn, Mary Tudor, and so many other interesting characters shaping events. What better way to really understand that pinnacle point in history than to scour the private notes and journals of a major player? In Tim Ellis’s The Secret Diaries of Juan Luis Vives, we have just that opportunity.

An archaeologist and historian by trade, Tim agreed to field a few questions about how to bring history alive from reviewer extraordinaire Karen Rigby: the author of the review of The Secret Diaries of Juan Luis Vives for Clarion. We thank them both for their lively repartee.

Karen, take it from here.

Juan Luis Vives—a Jewish humanist and scholar—endured the Spanish Inquisition, lived in Belgium, and was close to the English royals. He’s an uncommon subject. Fear follows him wherever he goes. What drew you to him, and to his era?

Great question, thank you. Vives is a fascinating character—once you find him. He doesn’t feature significantly in the English historical narrative, but he is well known in Europe. His influence was significant; he instigated great social change in terms of care for the poor and for the mentally ill. He spoke about the importance of education for women, of the rights of animals, and of literacy for all. Vives has also been dubbed the Godfather of psychoanalysis (Zilboorg 1941) and the father of modern psychology (Watson 1915).

So he’s fascinating before you get to the nitty-gritty of his personal life, which is where the story really picks up. The Spanish Inquisition had destroyed generations of his family. Vives’s father, grandfather, and great-grandfather were all burnt at the stake; he witnessed the burning of his aunt as a young child. Several years after his mother had died of the plague (bad enough for a nine-year-old son), her remains were exhumed, and they too were burnt at the stake. Her crime was visiting a clandestine synagogue twenty years earlier. He had experienced privilege, but by the age of sixteen, he was on the run from Spain, never to return, and his family wealth was ultimately confiscated. He went first to Paris, then to Belgium, then to England, finally back to Belgium. No surprises then that he was racked with fear—and admirable that he refused to hide away. Vives had things to say, and he was prepared to risk it all to say them.

Personally, I feel that the Tudor period is tangible; I can feel it and sense it. I can’t honestly feel that for, say, the Byzantine or the Plantagenet periods. I think that the Jewish experience within the Renaissance period needs to be heard. The Spanish Jews were fragmented, on the run, some converted to Catholicism, others pretended to convert. Nevertheless, they were well-educated, cosmopolitan, and influential people whose legacy has an impact on how we live today.

Still, I chanced upon Vives by accident, having gifted a friend whose family survived the Franco regime a book on the exiles from Spain (The Disinherited: Exile and the Making of Spanish Culture, by Henry Kamen, 2008). I turned to the section on the Jews of Spain before I (reluctantly) handed the book over. When I read Vives’s life story I searched for the film, the book, the novel, and to my surprise, I found none, and so I got to work with my writing before somebody else beat me to it!

Your background is in archaeology. The leap to historical fiction seems natural and clear. Would you talk about your writing process and research behind the novel? Any surprises?

Yes, I’d love to talk about that. History and archaeology have always been my passion. I worked for the Museum of London, and I was a tour guide at the British Museum. I emigrated to Australia from England in the early 2000s (changing careers in the process), but I couldn’t keep away from the past! The advent of the internet ensured connectivity with my passion, and as a creative, I had to write. I discovered that my mind is more creative and imaginative in the mornings. When writing the novel, I rose early, walked the dog, avoiding people wherever possible—just to keep my mind clear—and then I wrote. I found that in the afternoon and evening, my creative vocabulary is more limited. That’s when I could do the research, and check my story for detail: character, plot, and voice.

When you write about a historical person, especially using an intimate form, like a diary, how free or constrained do you feel about imagining their thoughts? Working between the story’s demands, and the need to stay close to the real person—their speech, plausible behavior, and own words, if they’ve left enough traces behind to know about—do you find particular challenges?

My feeling is that, with historical fiction, you simply have to go there. Writing in the first person, I had to be brave enough to become the character, if only for an hour or two, each day. I had to learn everything I could and allow myself to free fall until I felt that Vives was writing through me. I’m not claiming mediumship, and I don’t know if I am doing him justice or not, but, by consistently going there, as best I could, I was able to write authentically, and I could keep his voice consistent. Vives felt that connection with the soul was vital, and that clarity of speech was essential. So I had to channel all of that—it was rather like being a character actor—and was a marvelous escape from the real world.

He wasn’t flawless, and I had to show that. I also had to spend some time getting to know my minor characters—and letting them get to know me. I had to go there with them, too. You just can’t have wobbly, indifferent, or poorly voiced characters in a novel like this.

Were you conscious about modern readers—many of whom have never come close to extreme persecution—and how to make Vives’s everyday reality tangible?

Yes, very much so. In my life and work, I have met Holocaust and war survivors, refugees, and even abuse survivors. However, that’s not normal for everyone, and I have to find common ground. I see gratuitous violence in literature or film as unnecessary, but I can’t skirt around the realities of Vives’s life, and a bland story is of no interest to anyone. Getting the voice just right in historical fiction is ever-challenging. It has to reflect the subject—especially when you’re writing in the first person—but it can’t be abstruse or archaic. Vives would have liked his story to have been comprehensible to as many as possible, and I hope that I have done him justice.

Serious topics, like living in exile and facing xenophobia, are timely as ever. Any lessons we can draw from the book about surviving trauma?

I hope so. Modern science suggests that the brain, traumatized in childhood, has a permanently altered neurophysiology. Hyperactivity of the amygdala and alterations in the excitability of the limbic and the autonomic systems become permanent. Vives wrote about somatic reactions being triggered by sensory events; he was in effect pre-empting what we now know about post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and panic attack.

In terms of lessons in surviving trauma, and xenophobia, we can look at Vives’s life. He surrounded himself with people he could trust; he took his time establishing dependable relationships. He understood the importance of discernment, as well as restraint of pen and tongue. Despite frequently feeling emotionally triggered, he worked against the gut instincts that would have him retaliate and lash out. In effect, he knew that he had to work with himself to not making matters worse. Despite the trauma, Vives had fun—with words and with people—and he saw the beauty in the world. He struggled with intimacy, but he allowed love—and healing—into his life. He didn’t push people away or alienate them; he also practiced forgiveness.

You’ve lived and worked in England. Would you talk more about the chapters set there, and how your interest in court intrigue came about?

Yes, I did, and I loved it. I lived in London for eleven years, and my family, the Elishas, who lived and worked in “The Flying Horse” in Houndsditch—albeit in the eighteenth-century—feature in the novel. I love the hidden alleyways and those chance peaks into the medieval era—particularly in the east of the city—that London gives you.

As for court intrigue, I remember visiting Hampton Court Palace and seeing the sculpted wooden faces of “the eavesdroppers” in the beams. They hinted that every word, every gesture, was being overheard by somebody, who could have an agenda that opposed your own. You’d have to have some courage, emotional intelligence, and wily survival skills to negotiate all of that and keep your head. I take my hat off to anybody brave enough to even try!

Let’s set the darker aspects aside. The book includes fun elements, too. De Castro is enigmatic, even a little swashbuckling. Vives’s closeness to Margaret Roper is daring, to say the least, and Anne Boleyn—she’s a schemer. They’re all very human. Did you have any specific sympathies toward them or favorites? Why?

You simply have to have fun in a novel like this, and it can’t just be the odd swear word. Tudor era novels can seem dark, and the grisly fate of the main characters inevitable. I tried to get around that with banter, practical jokes, and, in the comfort of my own home, by whiteboarding relationships. Vives has a daring exchange with the Henry VIII—admitting to the king that he wanted to psychoanalyze him. Thomas More bows to Vives’s intellect, but he is committed to staying one step ahead of him. Although More is becoming increasingly insecure during the period of the novel, the witty repartee between the two of them keeps things fresh and real. Vives says, “what you can laugh at, you can rise above.” He was anything but flawless, and he could see the humor in that himself.

There is a beautiful bond between Margaret Roper (the daughter of Thomas More) and Vives, one that can’t ever be thoroughly enjoyed or explored. They were both married, and they understood commitment and fidelity. Still, they couldn’t deny their feelings for one another. A writer has to take a stance on Anne Boleyn. Anne was so amazing, and as soon as she loses her head, as far as I am concerned, the Tudor narrative loses its pizazz, its greatest asset. I love Anne, and I was working against my admiration of, and sympathies towards her in my book. Vives, who in my novel first meets Anne in Paris (historically plausible), acknowledges her wit and intelligence, and they consider working together, but soon discover that they can’t. He has tremendous loyalty to the beleaguered Catherine of Aragon.

If you were a girl in the early 1520s, you’d probably prefer to go on a date with Alvaro de Castro, than you would with his best buddy, Juan Luis Vives. Alvaro is dashing, smart, witty, and he doesn’t need external validation. He’s also a crafty spy, with a secret mission. He befuddles even the wily Vives, and is something of a James Bond of the era. Yes, Vives apart, it is safe to say Alvaro would have to be my favorite.

Last but not least, I am pleased to share the news that my book hit number one in the Spanish Literature category on Amazon earlier this month.

Thanks so much for the interview!

Karen Rigby