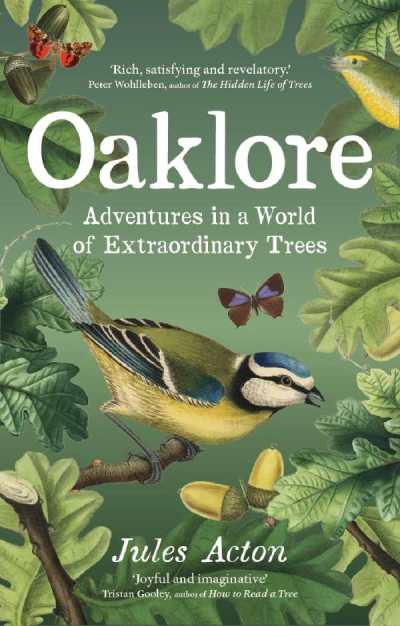

Reviewer Kristen Rabe interviews Jules Acton, Author of Oaklore: Adventures in a World of Extraordinary Trees

Curiosity is the telltale of a lively mind, the driving force behind so much human discovery, innovation, and creative ingenuity.

And while it’s one thing to be curious about sexy things like your favorite celebrity’s brand of toilet paper or how Roman soldiers managed to father an average of eight children apiece with Indigenous women while stationed in England in the 1st century, today, we’d like you to point that curiosity needle in the direction of plants and birds and rocks and—yes, the mighty oaks scattered across the the United Kingdom.

Jules Acton, the author of Oaklore: Adventures in a World of Extraordinary Trees, is taking a break from her job at the Woodland Trust to talk with Kristen Rabe about those towering life forces where upwards of 2,300 species of plants, animals, and fungi find sustenance and shelter.

(Check out Kristen’s review of Oaklore, as well as her reviews of four other curiosity-driven books in the Science Foresight in Foreword’s September/October issue. And, register for your free digital subscription here.)

Enjoy the interview.

Most of Britain’s ancient woods were cut down centuries ago. What is the significance of the remaining woodlands?

Oh it is immense. Ancient woods—which are broadly equivalent to North America’s old-growth forests—are the richest and most complex land habitat in the UK. Their soils have been undisturbed for centuries. They form the basis of vital habitats for animals, plants, and fungi.

Ancient woods are irreplaceable but they now cover only 2.5 percent of the United Kingdom and, tragically, many of them are under threat.

Why did you choose oak trees as the iconic British tree? How do they figure in culture?

Oaks are in our art, our place names, our pub names, our songs—sailors used to sing, “Hearts of oak are our ships, jolly tars are our men”—and in our brands too. Our islands are awash with oaky imagery.

Many writers—including Shakespeare—have paid homage to the oak, while others invoke the oak to express majesty, safety, or continuity. In Far from the Madding Crowd, Thomas Hardy called one of his characters Gabriel Oak, and with that one word signalled that his hero was solid, constant, and reassuring.

The oak is threaded into all parts of the UK’s culture. But, while we tend to think “oaks are us,” we should remember that oaks of different species grace large parts of the world. The oak is the national tree of several countries including of course, the USA.

The Ancient Tree Inventory catalogs many of Britain’s oldest trees. Describe a few of the most interesting oak trees on that list.

Ooh, it is so hard to choose. OK, let’s try.

The Big Belly Oak in Wiltshire is a big, bulging beast of a tree. And it is fascinatingly spooky. At some point in the past someone strapped it up with a great, rusting girdle of iron. Around this metal band swells a bloated trunk with dark holes that gape like giant mouths, while up aloft, immense, twisted limbs loom above your head making you feel tiny and maybe a bit scared. It is said that, if you dance twelve times anticlockwise around this tree—naked—you will summon the devil.

The Bowthorpe Oak in Lincolnshire is more your classic beauty. Its hollow trunk is so massive that they say it was once used as a venue to host tea parties. You wouldn’t do that now though—we now know it would harm this precious plant which we think could be 1,000 years old. Imagine the history it has seen. It was already a very old tree when the Mayflower sailed for America in 1620.

The Bowthorpe Oak is among twelve magnificent oaks currently up for the title of Tree of the Year. Others include Castle Archdale Oak in Enniskillen, Northern Ireland, a stunner with two towering stems; and the Skipinnish Oak in the Scottish Highlands, which is draped glamorously in lichens.

You note that an astonishing 2,300 species of plants, animals, and fungi find food and shelter in oak trees. Give a few examples.

My favourites include the tiny marble gall wasp which has had a big impact on our history. The larva lives in a marble-sized gall on the tree and these galls were used to make ink for centuries. This kind of ink was used to write Shakespeare’s plays, Charles Darwin’s letters and, on July 4, 1776, the declaration of America’s independence from Britain.

The Long-tailed tit is another great character. It makes nests that are shaped a bit like an American football ball (but less pointy). The birds add spider silk to these nests to make them stretchy, which means they can expand to fit the birds’ growing families. And they decorate them beautifully with flakes of lichen.

Lichens themselves are fascinating. Oak moss (a lichen, not a moss) is beautiful for its grey-green strands and its woody, slightly sweet scent. It is a key ingredient in some perfumes.

Your book focuses on UK locations and species. How can audiences outside of the UK apply your insights? Does Oaklore demonstrate a way of observing the world—in addition to highlighting a particular type of tree?

You could apply the same approach anywhere: take one tree and use it as a lens, exploring the ways it connects with the wider world. In the US, you could, of course, do the same with your own oaks. Please do it and have fun along the way.

You have been involved in several organizations that encourage preservation and awareness of trees and woodlands. What is the importance of these activities as locations around the globe are affected by climate change?

Trees are our foot soldiers in the fight against climate change and nature loss.

In my day job I work for the Woodland Trust. I do this because I think it is one of the most positive ways I could spend my working life. I see firsthand the immense impact of protecting woods and trees and creating new woods. For example, we started creating the UK’s first Young People’s Forest only five years ago on a former coal mine. The transformation is incredible. Already some of the trees there are waving their leaves above our heads and the nature they support—birds, butterflies, and beyond—has burst into life. If you get the chance to join the Woodland Trust as a member please, please do, you will be making a real difference.

And if you already support a conservation organisation, thank you. Is there anything more fundamentally important than caring for the nature on which we all depend?

Kristen Rabe