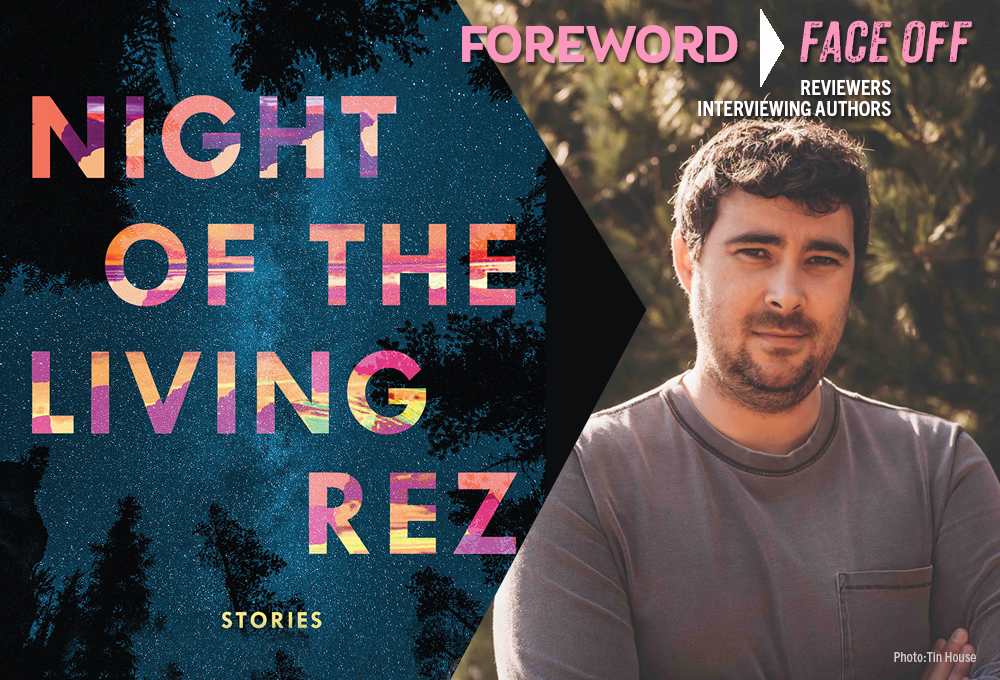

Reviewer Kristen Rabe Interviews Morgan Talty, Author of Night of the Living Rez

The United States federal government recognizes 574 Native American tribes, while the nation’s 326 Indian reservations amount to a total of 56,200,000 acres, 2.3 percent of the United States.

Big numbers, yes, but the sad fact is that most of us know next to nothing about life on those reservations, about the people living there, proud descendants of ancestors who suffered from US government-sanctioned genocide. This country did a horrendous thing to the Indigenous population living in North America, and it’s unconscionable that some legislators won’t allow the teaching of this history of violence in our grade schools.

This week’s guest author, Morgan Talty, was raised on the Penobscot Reservation in Maine, and he has some short stories about his people that he’d like to share with you. Morgan’s Night of the Living Rez earned a starred review from Kristen Rabe in Foreword’s July/August issue, which led directly to this conversation.

This short story collection is stunning, a powerful and heartbreaking look at a Penobscot boy and his family, living on a Native reservation in central Maine. Although their island “rez” is isolated and impoverished, the characters in these stories are survivors, determined and resilient. What do you want readers to know about the Penobscot nation? How does their history compare with that of other Indigenous people?

First, thank you so much for those kind, kind words. Truly. I’m happy the book resonated as such!

I really want readers to know that we exist—that we have existed and continue to persist into the future, even if tragedy may strike as it has in the form of colonialism. This collection is very much focused on the same characters, and so I never sought for this book to be representative of the Penobscot Nation—just one glimpse. To monopolize that experience, I think, is to perhaps overgeneralize but it’s also a form of violence: it’s a type of silencing of others’ voices from my tribe who I know one day will come forth with their own stories, adding to a more accurate picture of what it means to be Penobscot.

When it comes to comparable history, I always say that each tribe is unique in their sufferings and blessings, in their failures and successes, but the one thing that binds us all together is the violent history of colonialism as a broad term.

The short stories are all narrated by David, a Penobscot boy, and follow his experience from childhood to early adulthood. Even though the situations he describes are bleak, David has the strength and perspective to find humor in addition to pathos. Why is it so important that David tell these stories?

Because who will if not David? David is giving this record of one family and their struggles as well as the deep love they share for each other, the very love that keeps them going. So perhaps it’s for that reason it’s so important he tells these stories: to show or remind readers how powerful love and forgiveness are.

David and his friends struggle to find meaning and direction. While David seems to do okay in school and, near the end of the book, mentions a job as a UPS truck driver, he and his friends lack opportunities and mask their pain with drugs and alcohol. One of his friends concocts a disastrous scheme to steal Native artifacts from a museum and sell them, inspired by Antiques Roadshow. Are David’s struggles particular to him, or are they emblematic of the challenges facing Indigenous people overall?

I think they’re unique to him, but I imagine people who read the book may find a part of themselves in there—whether the reader is Native or not. The curse of addiction is a human problem, and I wanted to make sure it came across that way instead of as something indigenous people deal with. The act that resulted in that addiction, though, might be different depending on the reader and their experience.

Your own experiences, as a member of the Penobscot tribe, parallel David’s in certain ways, and yet you’ve achieved things that seem out of David’s grasp. You attended Dartmouth and have found success writing and teaching. Please talk about the mentors or other opportunities that have helped you.

I wouldn’t be where I am today without my family and my community, the Penobscot Nation. They have cheered me on since the beginning. I continued my education, and in doing so I met so many teachers and mentors that helped me get where I am, starting in elementary school all the way to my MFA program and even beyond. People believed in me, encouraged me, pushed me. And now that I’m here, I want to do the same and have been trying to for others.

The imagery in these stories is haunting and vivid. I think of the young boy’s prized plastic bin of toy men, which he sacrifices during a family crisis—or, later, the stench of thousands of crushed caterpillars on the road as David drives his friend home from electroshock therapy. The images are integral to the tone and theme of the stories. Talk about your writing process. How do you surface such powerful and unexpected images?

It really comes from living: trying to take in as much of life and its beauty as you can. I keep a huge running list of things in my notes, ranging from images that I thought were striking or strange situations that have come to me throughout the day. When it comes to surfacing that power and unexpected image, it’s about two things: finding the unique image and then channeling emotion to it—thinking about the ways we can build around the image with character to imbue that object/image with feeling.

Some of the most touching scenes in the book are David’s interactions with the women in his family—his mother, sister, and grandmother. Although these women each face oppressive challenges of their own, there’s clearly a strong bond and tenderness among them. How have these female characters influenced David? Are there echoes of your own mother or family in these relationships?

There are totally echoes! I grew up with mostly women and feel most comfortable around them. These female characters have influenced David in some of the same ways they influenced me: they made me a better person.

What are you working on now? I ended up caring deeply about David and want to know what happens next. Will you continue writing his story?

I don’t think I’m done with David just yet—who knows! I may return to him. But for now, I just finished revising a novel, Fire, Exit, that is a story whose situation is fueled by the colonial tool of blood quantum. And, I’m also working on a collection of essay pieces, sort of similar to David Sedaris’s approach.

Kristen Rabe