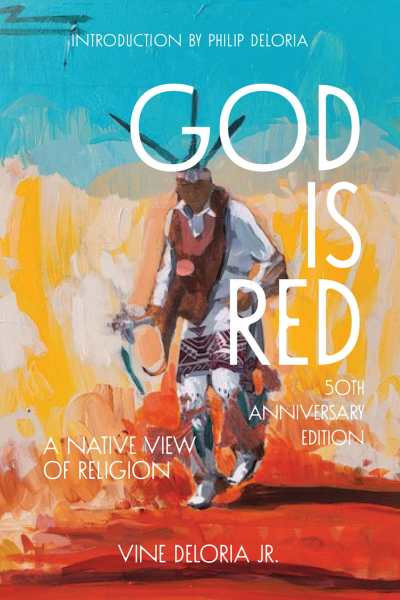

Reviewer Kristen Rabe Interviews Philip Deloria, Son of Vine Deloria Jr., Author of God Is Red: A Native View of Religion: 50th Anniversary Edition

Over the months of FTW Thursdays, we’ve talked many times about the declining numbers of white evangelical Christians in the USA—from 23 percent of the population in 2006 to 13.9 percent in 2022—but we really haven’t heard a good explanation for why it’s happening.

Today’s featured book offers a stunning theory: “Christianity might be ineffective outside of the holy land. It’s not really cut out for the Americas.” In other words, “Christianity’s success as a world religion reflects its strategic alliances with several empires in various ages of imperialism, rather than its spiritual efficacy.”

Now there’s a shot across the bow. Philip Deloria, how about another revolutionary idea from your dad’s book.

“The [spiritual place] argument also suggests that Native spiritualities, as practiced in their home landscapes, have continuing power, even after centuries of hard history in which settlers tried to suppress those practices. That provocative viewpoint sits at the core of the book: it is a critique of Christianity and an assertion of the importance of Indigenous spirituality.”

On the occasion of the 50th anniversary of God Is Red, Vine Deloria Jr.’s seminal work on Native religion, son Philip agreed to take a few questions from Kristen Rabe, she who reviewed the anniversary edition of the book in Foreword’s July/August issue.

Your father first published this book in 1973. Tell us a little bit about your father, and explain why writing this book was so important to him.

My father grew up in the Episcopal church. His father was Native clergy serving in South Dakota, and his grandfather also studied religion. So, it was natural for my father to study the subject, earning a degree from the Lutheran School of Theology.

In the 1960s, as the Black church was so prominent in the Black Civil Rights movement, my father began to consider what role Christian churches, with their long histories of missionary activity, might be playing for Native people. He served on the Episcopal church’s governing board, and he tried to raise the issue of Native affairs with church leaders. He was, in many ways, an institutionalist, but he wasn’t satisfied with that particular institutional approach. Writing God Is Red was important for him because it allowed him to connect his political and legal insights with his interest in religion. The book is partly a critique of Christianity and its missionary history, but it goes beyond that to assert the power and promise of Native spiritualities.

The book addresses common stereotypes of Native people in popular culture, including images of brutal warriors stalking settlers as well as calm, stately elders dispensing wisdom. How did these images take hold? How have they affected Native peoples’ struggle for civil rights?

In most of his early writing, my father included one or two introductory chapters in which he names, discusses, and tries to dismantle longstanding stereotypes. His objective was to help readers move beyond longstanding cultural and ideological structures so that they could maybe hear more clearly what he was trying to say.

These stereotypical images have served certain purposes historically. For instance, when violent conflict over land was at stake, it made sense to frame Indians as warriors attacking. Conversely, when those struggles seemed to be concluded, it made another kind of sense to portray Native people as wise and stoic, figures in touch with nature and spirituality. Every time Americans engaged Native people, such stereotypes came into play. These images have piled up together over time—and continue to do so today.

Perhaps most pernicious of these myths is the idea that Native people were doomed to vanish, and indeed actually had vanished. When Americans imagine that Native people do not live in the here and now, it makes it much easier to dismiss their struggles for sovereignty and treaty rights.

The book also challenges romanticized views of Native religion, such as New Age popularization of shamans, sweat lodges, and “medicine men” who work the lecture circuit. How are these secularized ideas detrimental to traditional religions?

Stereotypes are often negative—concerning Indian savagery, for example. But people also create positive stereotypes, and we should not assume that the latter is somehow better. The image of the all-knowing Native mystic, possessor of some fantastic spiritual secret, has led to a kind of New Age popularization; ideas about Native spirituality are converted into seminars, retreats, assertions about cultural authority, and cold hard cash.

At the same time, my father was quite sympathetic to people seeking to encounter Native knowledge to understand something about the world. Indeed, he argues that “God Is Red” in North America (i.e., “this land”), and he suggests that, if we’re all going to solve the problems of our future together, non-Natives need to acknowledge Native spiritualities. This understanding opens a path for engagement, but it is also foundational if we’re going to address our shared challenges.

One of the most fascinating aspects of the book is its discussion of spatial vs. temporal thinking. Native religions are closely tied to place and emphasize a kind of “sacred geography,” while Christianity is based on a timeline of “historical” events. What are the implications of these contrasting sets of beliefs?

The argument locates spiritual traditions in specific places, and it suggests that any tradition will not be effective or meaningful outside of its particular place. In other words, land matters! Christianity began with ties to the biblical holy land, but it has transcended its place through missionary outreach. The book argues that Christianity might be ineffective outside of the holy land. It’s not really cut out for the Americas.

Following this logic, Christianity’s success as a world religion reflects its strategic alliances with several empires in various ages of imperialism, rather than its spiritual efficacy. The argument also suggests that Native spiritualities, as practiced in their home landscapes, have continuing power, even after centuries of hard history in which settlers tried to suppress those practices. That provocative viewpoint sits at the core of the book: it is a critique of Christianity and an assertion of the importance of Indigenous spirituality.

Discuss the differences between Native creation mythologies and traditional biblical creation stories, including the Christian concept of a “fall” into sinfulness. How do these differing beliefs affect assumptions about the natural world, death, and the afterlife?

The fall into sin is also a fall into history, out of sacred time and into the secular. In one of its foundational concepts, then, Christianity is structured around a binary and a distinction. If the world is here and God is there, then the question is always about how one bridges that separation. Christianity suggests that the answer comes through sacrifice, supplication, prayer, prophecy, and ultimately the figure of Jesus Christ (and even after that, through miracles and transubstantiation). Christianity places its followers in a complicated and perhaps even untenable position, suggesting that, in this life, any resolution to the original separation is only temporary and incomplete (and often unsatisfactory). Its permanent resolution will come with the end of history; thus, linear temporality is embedded in the religion—requiring a beginning, middle, and end.

Native origin stories may speak of early times, but they just as often reside in particular landscapes. They are not only invoked; they are experienced. Temporality is not exactly cyclical, as is sometimes claimed, but rather it is full of possibilities. My father was deeply interested in the thought experiments posed by physicists, which he thought might help describe how one could find oneself in multiple temporal experiences. The bottom line is that there is little separation between the human and the divine. Human divinity and power is matched, overlapped, gifted, and connected to the divinity and power of animals, plants, stones, water, and everything else that is here, among us, on this planet.

The lines between life and death are also less rigid, and less likely to be attached to judgments about moral and ethical behavior. Native societies developed other mechanisms to encourage ethical behavior, rather than the threat that one might pay for one’s transgressions in an afterlife. There are plenty of mysteries, ghosts, and uncertainties in Native worlds, but they cannot be oversimplified into overly rigid systems. Native people recognized the uncertain and contingent nature of their own knowledge. Rather than being handed religious dogma, Native people saw the world as something to experience and puzzle out. They used the guidelines of belief and tradition, to be sure, but they also valued the constant reinvigoration of those things through an ongoing experience of revelation.

The book calls for us to undertake a “more profound explanation of ourselves and the planet on which we live.” What are the crucial next steps? What can we learn from the experience and beliefs of Native people?

I mentioned that my father was interested in theoretical physics and its complex descriptions of time, space, possibilities, positions, multi-verses, and the idea that the observer/actor can be an agent in events both at the (sub)atomic level and at the scale of the universe. He rejected the idea that the West had “science” and the rest had “superstition.” In fact, he saw Native spiritualities as a generative practice that refused those categories. I think that this is the kind of thing he had in mind when he wrote of a “more profound explanation.”

We’ve already seen other sciences—ecology, in particular—articulating concepts of interspecies relationality that sound familiar to anyone who knows anything about Native spiritual systems. After centuries of condescension, the sciences are recognizing ideas that have long been central to Native people. Perhaps it’s time, not to pillage and appropriate yet another element of Native life, but to seek collaboration and partnership, to repair and build good relations for the future.

Kristen Rabe