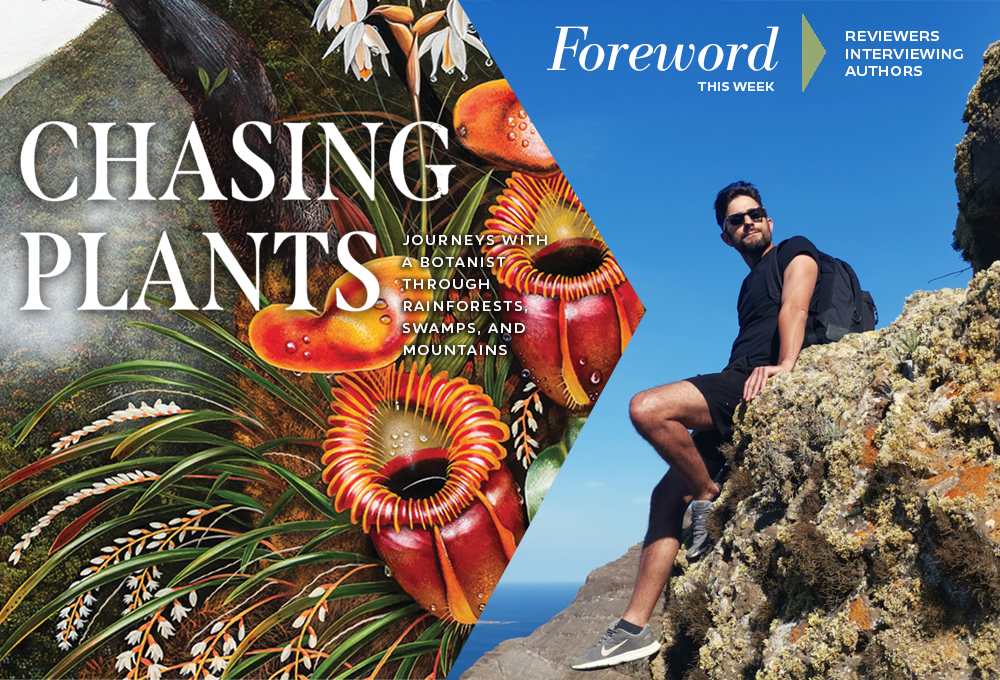

Reviewer Kristine Morris Interviews Chris Thorogood, Author of Chasing Plants

A couple days ago in Montreal, 190 countries agreed to protect thirty percent of our planet’s land and oceans within seven years. That’s a big deal!

The NYTimes reports that the agreement also included a “slew of other measures against biodiversity loss, a mounting under-the-radar crisis that, if left unchecked, jeopardizes the planet’s food and water supplies as well as the existence of untold species around the world. Researchers have projected that a million plants and animals are at risk of extinction, many within decades. The last extinction event of that magnitude was the one that killed off the dinosaurs 65 million years ago.

This week, it’s our good fortune to hear from Christopher Thorogood, a botanist at the Oxford Botanic Garden and the author of Chasing Plants: Journeys with a Botanist through Rainforests, Swamps, and Mountains. Addressing biodiversity is Christopher’s life mission—along with doing some radical climbing and clambering at remote locales around the world looking for rare, endangered, often carnivorous plants.

After we sized up her starred review of Chasing Plants in Foreword’s November/December issue, we planted the seed for the following interview between Kristine Morris and the derring-doer, Christopher.

Happy holidays!

Your book, aptly titled Chasing Plants, has you traveling to exotic locales to find and record the existence of plants that may be new or unfamiliar to most, and that also may be among the two in five plants worldwide that are threatened with extinction. Most people think of plants as static—even boring—as they don’t chase and kill prey or engage in wild, exuberant mating rituals the way some animals, or birds, and even some humans, do. What is it about plants that so captured your imagination in childhood and led to your career in botany?

What sets animals and plants apart is the fact that animals move on our timescale. We’re hardwired for seeing animals: they move and we notice them—we evolved to do so, to hunt them or avoid them. But see past this and you enter a mysterious world in which plants trick, hunt, and often even outsmart animals. A green and beautiful world that’s all around us. This is what piqued my interest.

I always loved science as a kid. I needed to know why things worked. I grew plants—hundreds of them—and so my bedroom was sort of a living laboratory for me. I loved animals too, especially marine invertebrates (starfish, sea cucumbers, and so on), but plants possess a serene and intricate beauty that once you’re tuned into, you can’t ignore.

You’ve called your adventurous career “extreme botany,” and in your book you’ve shared some pretty perilous plant-chasing adventures. How often do you have to think twice or more about climbing or hanging from that slippery cliff, fleeing volcanic eruptions, or facing typhoons to get a good look at an interesting plant? What is there about you that makes you decide to go for it?

I actually consider myself to be a risk-averse person in most compartments of my life! Or, at least, I’m far from reckless. But I’m not motivated by the extreme acts themselves; rather I am driven to go to extremes to find the plants. Often plants thrive where people don’t—for example, on remote cliff ledges that remain untouched by human progress.

Though I must add that I’m unafraid of heights—if I’m honest with you, a little part of me loves them.

What do you do to stay in good enough shape to face the challenges of such work?

I used to run long distance (marathons) but I don’t have time these days, unfortunately. But I rarely sit still, and the plant-hunting itself keeps me in pretty good shape!

What do you consider to have been your most extreme plant-chasing adventure so far?

I prefer to ponder on what might be my most extreme plant chasing adventure still to come! I would love to visit some of the remotest rainforests in Southeast Asia; the region is home to some of the most extraordinary and diverse wilderness you can find anywhere on our green planet, and I’ve only seen a sliver of it.

Is there a type of challenge you would not undertake to get a good look, photo, sketch, or sample of a very special plant?

No.

You also wrote about finding some pretty significant plants in places as mundane as the parking lot of an IKEA store in Essex, or along common roadsides and paths that people use every day without noticing the plants growing there. What might be the cure for such “plant blindness?”

Spend a moment in any place and look. If you don’t see something remarkable, look harder. Just about every outdoor space holds something special. Mosses, for example, pre-existed most of the other plants we see about us, and once formed great continents on land long before trees evolved. They long pre-date human life and they have a serene, timeless beauty to them. It’s all about looking closely, taking the time.

To what degree does your research focus on carnivorous and parasitic plants, and why have you chosen this focus?

I love them and I always have. Just this week I have been teaching undergraduate biology students about them. And I am currently working with mathematicians to examine the slippery surfaces of carnivorous pitcher plants and how they vary with geometry. Work like this keeps me up at night thinking!

What is the importance of carnivorous and/or parasitic plants to the ecosystem? And are they early or late arrivals in the history of plants on the planet?

Late arrivals, relatively speaking among plants. They both evolved from “normal” (photosynthetic) ancestors in the flowering plant family tree, on multiple occasions.

Parasitic plants are especially important in ecosystems. Like Robin Hood, some of these plants rob the rich (grasses) to feed the poor (other flowering plants), and they have a profound impact on plant communities.

How and why did carnivorous plants evolve, and are there signs that new strains of such plants may be developing?

Carnivorous plants evolved in response to nutrient stress. They arose in environments where nitrogen (important for plant growth) is missing—for example, in acidic, rain-leached places like marshes or mountain slopes. Feeding on animals (insects, for example) gives the plants a boost—in evolutionary terms, a “selective advantage,” as they are more likely to survive, prosper, reproduce, and pass on their genes to the next generation. Over the course of many generations, their arsenal of traps have become ever more complicated and effective in the struggle to survive and reproduce.

Your book calls attention to the urgency of finding, recording, and learning from plants, as our very survival depends upon them. What about the current situation most concerns you, and do you see any solutions?

Indeed, plant diversity is in free-fall in so many places, and it can be difficult at times to remain optimistic in the face of human-driven change. I try to focus on where we do have control: local and international conservation programs, for example. At Oxford Botanic Garden (where I work), we cultivate rare native flora. Just last week we planted seeds of a parasitic plant that is extinct in our county (Oxfordshire) to re-establish the plant. It won’t change the world, I know, but making lots of small changes all over the place will make a difference. We must look for where we can make positive changes, however small.

What are some of the most important things that humans can learn from plants?

Honestly, we don’t know. There are some 400,000 species of flowering plants, and we’ve barely scratched the surface of what they all are and how to name them, let alone what we can learn from them. I am particularly interested in what we can learn from Indigenous communities who live alongside plants and know their uses intimately. We can learn a lot from them, I’m sure.

Your book mentions research on plants that has led to technological and design innovations. Which of humanity’s problems are being addressed by such research, and what appears to be the most promising line of research so far?

This year my colleagues and I published a paper on the strength and load-bearing capacity of giant waterlily leaves. We showed how the criss-cross framework making up the vascular structure of the leaves supports their large surface area and keeps them afloat. The giant leaves can grow forty centimeters a day, reaching nearly three meters in diameter—ten times larger than any other species of waterlily and capable of carrying the weight of a small child. I used to marvel at this extraordinary plant on childhood trips to botanic gardens. I remember wondering how on earth it could grow this big. Our work shows that the structure and load-bearing properties of the giant Amazonian waterlily give it a competitive edge: high strength at low cost.

The form of these waterlilies could inspire giant floating platforms, such as solar panels in the ocean. Remarkable structures in nature can help us to unlock design challenges in engineering.

You wrote that one of your goals is to astonish people with what’s extraordinary about plants, and your paintings, beautifully reproduced in your book, are astonishing, exquisite portraits of plants, their beauty highlighted against their natural habitat. Please tell our readers about your background as a painter. To what degree are science and art equal partners in your career?

Science and art are both lenses through which I make sense of the natural world, even if they seem very different. I’m a botanist, first and foremost, and I’ve always been fascinated by how things work, as I mentioned earlier. But drawing helps me make sense of a plant—to deconstruct something, to put it back together, to see it at the finest possible level of detail. To me, botany and art go hand in hand: art complements science.

Where might your paintings be seen?

I paint all sorts of plants for various projects. I recently produced some illustrations for a Herbal of Iraq—that was fun. I am also producing a series of watercolors of the plants of the Canary Islands. Most of my work is produced for books, and I often have a few on the go at any one time.

Your role as Head of Science and Public Engagement at the UK’s Oxford Botanic Garden and Arboretum involves enhancing public engagement with plant research. What are your goals, and which routes to engagement have you found most effective?

As a botanist and artist, I aspire to helping build a greater care and attention for plants and their plight. If I can do that even in a small way, then I am happy.

Kristine Morris