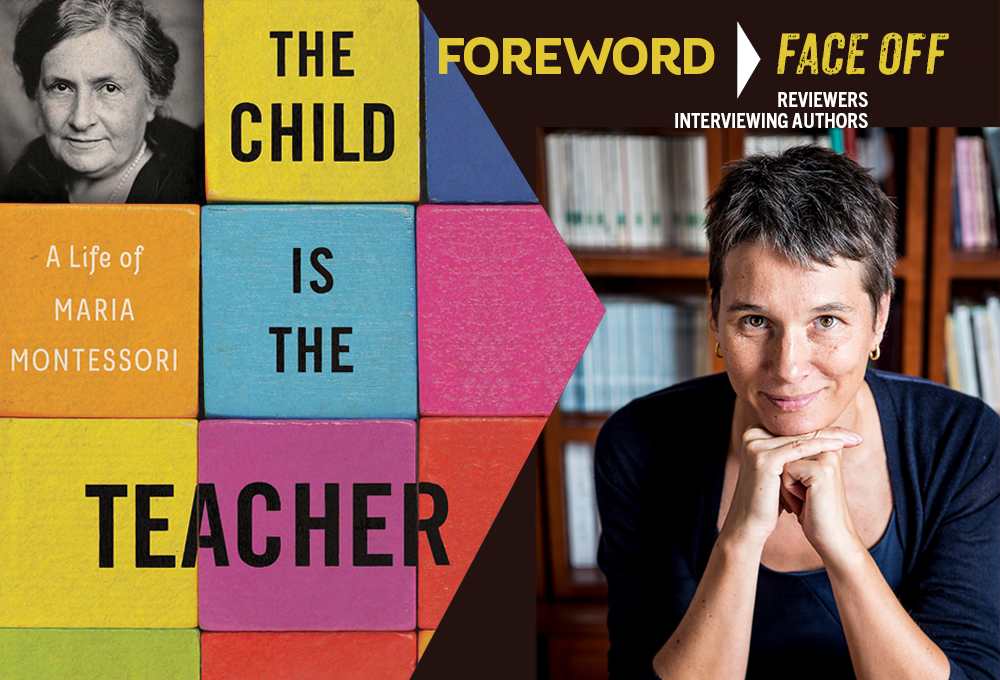

Reviewer Kristine Morris Interviews Cristina De Stefano, Author of The Child Is the Teacher: The Life of Maria Montessori

You know the esteemed international school by name and likely have an idea of their quite radical approach to educating children, but did you realize the “Montessori Method” was created in the early 1900s by a young single Italian woman who dismissed all the attention with the quip “I did not invent a method of education, I simply gave some little children a chance to live.”

This week, we’re here with Cristina De Stefano, author of The Child Is the Teacher, a fantastic new biography of Maria Montessori. In the interview below, Cristina admits the Montessori gig is difficult to grasp for some, but sums up the difference between the average public school and Montessori by saying that you need to approach it this way: 1) buy into the idea that children are very powerful and wild; 2) take the view that traditional schools are designed like a zoo, where the child works in captivity inside a cage; and 3) imagine the Montessori school as trying to be like a safari, where the child can move freely and the adult drives the car around to watch without disturbing him.

That works nicely for us.

Kristine Morris gave The Child Is the Teacher a starred review in Foreword’s March/April issue, so we did our thing and got the two together for the following remarkable conversation.

Reading The Child Is the Teacher, your book about the life and work of Maria Montessori, I had the feeling that you knew her very well—it’s almost as though she herself were telling the story and reliving her emotions. To what do you attribute the affinity you have for this woman, a genius who was far ahead of her time in so many ways?

I am happy to hear this, since it was hard work for me to get under her skin. Maria Montessori was a very complex character, with both nice and negative elements in her personality. On top of that she was a thinker, so I was dealing not only with the life of a strong woman (this is, in the end, what I specialize in), but also with a vast number of books, a method, and didactic materials. To make things worse, she was a woman of another time—she turned thirty in 1900—full Belle Epoque. How could I get to know her feelings, her way of looking at things, the reasons for the decisions she made?

When I started my research, I was really worried. That’s why I worked hard on the identification process, reading all her letters over and over, staring at photographs of her and of the times and places in which she lived. Rome at the end of the nineteenth century was an amazing city, moving directly from ancient times to the contemporary age, and so was Paris, to which she travelled to see Segue’s didactic material at the same time that Gustav Eiffel was building his tower.

Please tell our readers what your daily life looked like as you were researching and writing the book.

I have a very busy life since I am a journalist, a literary scout, and also an author. While working on the book I had a full-time researcher who, under my guidance, visited all the relevant archives, foundations, institutions in Italy and elsewhere. For months, I travelled in person to Amsterdam, where the AMI (Association Montessori International) has its headquarters and its archive—a real gold mine of information. I also travelled to Barcelona, since the Spanish period of Maria Montessori’s life was quite rich in new information. I read all her books, and all the books and papers about her—the bibliography is huge.

It was a lot of work, and I had doubts from time to time, since I am not a specialist in pedagogy nor a member of the Montessori movement. At the beginning this seemed to be a problem, but I soon realized that it was a positive force: looking at it all from the outside, you ask different questions, and sometimes you put a new light on things. The actual writing was fast and smooth, as it always is for my books—I love writing. But you have to get to the point where your mind is full of information, with everything in place. It is only then that something clicks and you start seeing the larger picture.

Your book shows Maria Montessori to have been a complex, sensitive, driven, and passionate woman, justly called one of the most revolutionary women in history. Born in 1870, in conservative, Catholic Italy, she overcame great obstacles to become a medical doctor, an educator, and a philosopher of education. An active feminist “determined to escape from the trap of the female condition” and determined to make a difference in the world, she had to make some very difficult decisions in order to follow her calling. Please talk about some of the struggles she faced, especially why she, as an unmarried woman, made the difficult decision to send her newborn son to be raised by others, and her surprising temporary association with Mussolini.

It is true, her life was full of struggles and surprising facts. First of all, she had to fight to attend schools and university—at the time, a woman of her social class was only supposed to find a good husband and smile. For Maria Montessori, marriage was never an option. That’s why, when she discovered she was pregnant (she was having an affair with a fellow doctor), she faced a terrible dilemma: marry her lover and give up her job as a doctor and all she had fought for, or give her baby away. She chose the second option. It is difficult to imagine how heartbreaking this was.

But she got her son back when he was 15, in a very exciting way that I explain in the book, and from that moment on she was never again separated from him and made him her collaborator and heir. Another surprise for me was to discover that in her youth she was very active in social work and feminist militancy. She was a revolutionary in a sense, but soon became more interested in changing the souls of people beginning with childhood than in changing laws or the rules of economics. The collaboration with Mussolini, which lasted ten years, was based on a huge misunderstanding—he wanted to use her name for publicity, and she wanted to change the school in Italy—and so was doomed to fail. In my opinion, this association cost her the Nobel Prize, for which she was a candidate three times after WWII.

With educational circles focusing so much on the “Montessori Method” and the materials involved, the revolutionary and transformative nature of Montessori’s message may be overlooked or misunderstood. Would you please clarify the underlying message of her work for our readers?

First of all, it’s important to understand that Maria Montessori wasn’t a schoolteacher, but a psychiatrist, so the core of her work was the study of the child. She made great observations on how the child learns, realizing that the child has a very powerful brain, with its own way of functioning. Maria Montessori’s message was simple: the child is a machine for learning. Let him work freely—he knows how to do it, and will do it if adults don’t get in his way.

In practical terms, her method is based on three pillars: a prepared environment (the classroom and its furniture should let the child move freely and choose desired activities), a prepared material (which is to be used by the child alone, incarnates a concept, and offers the possibility for self-correction), and a prepared teacher (the Montessori Method asks the adult to keep quiet and avoid intervening, except when it is really necessary—something that’s hard for adults). If you manage to do that, the child blossoms and develops the cognitive process in a complete way.

Here is a good image to describe the difference between a traditional school and the Montessori concept: the child is a very powerful and wild creature, and the traditional school is designed like a zoo, where the child works in captivity inside a cage. The Montessori school tries to be like a safari, where the child can move freely and the adult drives the car around to watch without disturbing him. The Montessori concept is very demanding, it requires a teacher who is willing to work deeply on himself.

To what degree have Montessori’s message and method been adopted by educational institutions and systems around the world that are not specifically Montessori schools?

Luckily, many ideas from Montessori—respect for the child, for example, or the notion that emotional stability is required for a child’s optimal development—are now considered to be common sense. The problem doesn’t lie there. Schoolteachers all around the world often do a terrific job and put a great amount of effort into everyday activities. The problem is that the school as an institution is still not built around the child, but around adults: the teacher, the program the system has decided to use, and the parents and their requests. The good news is that the child has such a powerful and amazing brain that he manages to learn anyway. But if we put him in the ideal situation—particularly in the first years, when he creates the basics of the whole cognitive process—he will be invincible.

I was very good at school, but today I realize that I am a zero in math, even when I have to calculate what I must pay a shopkeeper. When I got my hands on the incredible didactic material Maria Montessori created for the learning of math, I said to myself: “This is what I needed when I was a kid! A material that invited me to “touch” the numbers, with the sets of ten made with little pearls to show how they add or multiply.” Once you have this experience as a kid, you get the concept for your entire life. When you study math at school as abstract information that you have to memorize, as I did, you can lose it as soon as you are out of school.

What changes do you think we might see in our society if Montessori’s belief that putting the child at the center would “change everything forever” were to be adopted and acted upon?

That belief is something that can change everything, in both the private and public realms. Montessori used to say that we should create a Ministry of the Child. The child is often absent from political speech. Montessori’s ideas are not just for school, they are for everyday life, in the family and in society.

You devoted five years to your work on The Child is the Teacher, and had access to materials not readily available to others. What did you discover in Montessori’s character that you find admirable, what was less so, and what did you find surprising?

I admire her a lot for being so strong, confident, and focused. She wanted to leave a mark on the world—such a crazy idea for a girl who was born in 1870—and she did it all by herself, without being born rich, without a husband or a social position, and starting in Italy—a quite poor and marginalized country at that time. I admire her for being a visionary, with a capacity for observation that was often almost miraculous. There are elements of her personality I don’t like, though: her desire to control and her authoritarianism, for example. Surprising? Her idea of free love outside of marriage. In Catholic Rome, in 1890, that was pure madness!

How was such a powerful, driven person able to be such a patient observer of children and humbly learn so much from them? What discoveries did she make about them that are now being confirmed by scientists?

She was a scientist, and had the mindset that observation was everything. She looked at children as if they were an experiment. That was new, and led to a new approach. Neuroscience today confirms many elements that she identified a century ago: she spoke of learning through movement and manipulation of materials—now scientists all agree about the link between movement and the learning process; she discussed the different steps of learning—now scientists talk about the “executive functions” of a child’s development; she called the child’s brain an “absorbent” mind—now scientists talk about “synaptic pruning.” Maria Montessori’s assertion that intelligence is developed by sensory organs and coordination is now backed up by research. It is amazing how ahead of her time she was, without MRI scans or anything.

As a mother, do you agree with Montessori’s attitudes and beliefs about childhood, the way children learn, and what adults might learn from children? Why or why not?

Absolutely. She convinced me 100 percent. Unfortunately, it is too late for me: my two children are now adults. They survived their schooling, and today they are two incredible human beings, but I know that they were often unhappy during the whole process of attending school, especially my youngest son. If I had worked on this book twenty years ago, I would certainly have enrolled him in a Montessori school, at least for the maternal and primary levels.

How have the methods and materials developed by Montessori changed since her death in 1952? What do you think might be done to develop them further?

The material is still the same. It is so classic and so beautiful that there is no need to change it. Moreover, with the all-virtual, all-screen environment kids are faced with today, it is even more important that they develop the first cognitive elements in the practical, concrete way Montessori suggested a century ago.

What brought you the most satisfaction in writing The Child is the Teacher? What was most difficult or problematic?

While writing, nothing, to be honest. I was so worried about the result, fearing I would end up with a book that was too difficult, too technical, or too boring. This is not a book for specialists—I wanted to target a very wide readership. The problem was how to describe a woman of another time, and such a profound thinker, in a way that a large audience could get easily. My satisfaction has come from the response of readers. In the first countries where the book was published, I had great feedback through social media. I remember a young father who wrote to me that I had forever changed the way he looks at his baby. That’s great!

What was it like working with the excellent translator, Gregory Conti?

I read the translation that Gregory Conti did, and am extremely impressed with his ability to recreate the tone and the style of my book. I am very grateful.

Can we hope for another book?

Nothing in the pipeline for the moment. I am still recovering! There are several great women knocking on my door, but I don’t answer and I pretend I am not at home.

Kristine Morris