Reviewer Kristine Morris Interviews David Barrie, Author of Supernavigators: Exploring the Wonders of How Animals Find Their Way

Add this to the reasons experts warn us not to spend too much time with smart phones: By heavily relying on Google Maps and other navigational apps, you will definitely weaken the area of your brain that controls your sense of direction. It’s a “use it or lose it” situation—those circuits of your brain will shrink like an atrophied muscle. Furthermore, that brain region also plays a big role in your ability to make predictions, use your imagination, and even be creative artistically.

Serious stuff.

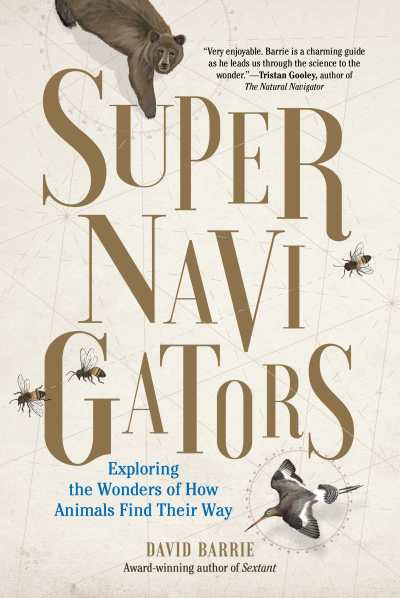

But let’s lighten up. Today’s interview topic explores the extraordinary sense of navigation known to many of our fellow creatures on Earth. Say hello to David Barrie, the author of Supernavigators, a fantastic new book from The Experiment that earned a starred review from Kristine Morris in the May/June issue of Foreword Reviews.

Yes, David’s book is filled with fascinating details of whales and birds and other creatures finding their way around the world without Google, but there are other important reasons to care about the message in this book. Let’s go to Kristine’s review: “Supernavigators makes it clear that the more we learn about the animal kingdom, the less evidence we find to support our belief that humans are distinct, separate, and superior. What does set us apart from all other species is that we are able to influence the fate of every other creature on the planet. Understanding the wonders of animal navigation may help us appreciate the small and large miracles that surround us and the value of all that we are putting at risk.”

Please enjoy this rather lengthy interview—and the next time you see an ant hustling across a sidewalk, show a little respect.

Kristine, take it from here.

What initially inspired your interest in animal navigation?

I think it all started when I was about seven or eight years old. I had a wonderful, eccentric teacher called John Steadman who ran a moth trap at my school in the south of England. The beginning of the day was always a thrill because I could join him in identifying all the insects that had been attracted to the light during the night. The variety was amazing! I remember my excitement each morning, wondering what new species might turn up. From Mr. Steadman I also discovered that some moths and butterflies only came to Britain as summer visitors.

I pestered my mother into taking me to the Natural History Museum in London where a young curator took us through an unmarked door into a vast room filled with cabinets containing millions of moths and butterflies from all around the world. I was in heaven! He pointed out one big, exotic butterfly which turned up—very occasionally—in England. I was surprised to learn that it came from North America. The magnificent insect, with its broad orange wings veined in black and speckled with white polka dots, was a monarch.

Back in the 1960s, the astonishing overwintering site where millions of monarchs gather on trees high in the mountains of central Mexico hadn’t yet been discovered by scientists. And once it was, we still didn’t know how the butterflies found their way there, in some cases flying all the way from Canada. Well, the mystery of the monarch migration caught my imagination and it set me off on the journey that led, eventually, to the writing of this book. And during my research, I was amazed to find that many of the puzzles of monarch migration had been solved.

For all animals, including humans, “finding our way” can be a matter of life and death. Of all the animals you’ve studied, which one impressed you most with its navigational skill, and why?

That’s a hard one! There are so many contenders.

I suppose the bar-tailed godwit may perhaps deserve the prize for sheer endurance. This land bird has been tracked flying non-stop from Alaska to New Zealand—11,000 km across the Pacific Ocean. The flight takes it a little over a week, and it loses a third of its body weight along the way. These birds can’t land on water because their feathers would get soaked and they wouldn’t be able to take off again.

But for accuracy, the monarch butterfly is pretty hard to beat. The southerly migrants in the fall have to locate tiny areas in the highlands of central Mexico where they can safely pass the winter months after traveling thousands of kilometers. We know that they use a sun compass to head in the right general direction, but how they find those small patches of forest is still a mystery.

But what about the great white sharks that have been tracked swimming from the Cape of Good Hope across the Indian Ocean to the west coast of Australia and back again? Or the bluefin tuna that migrate with great accuracy across the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans? Or the humpback whales that follow arrow-straight tracks across the open sea for days on end? Nobody knows how any of these animals do it, but these are astonishing feats of navigation.

Have there been any cases of humans who have shown an unusually acute sense of direction?

There’s been endless debate about the human “sense of direction.” There is plenty of experimental evidence that ordinary city-dwelling humans are very bad at maintaining a steady course when they’re blindfolded. We tend to go around in circles when we can’t see where we’re going! So, we rely heavily on visual landmarks.

But we can also make use of our other senses, notably hearing and smell. I was fascinated to discover that, contrary to what I was taught as a student of experimental psychology in the 1970s, we now know that humans actually have very sensitive noses. In fact, students wearing blindfolds and going around on their hands and knees sniffing like dogs can successfully follow scent trails!

But there are other possibilities, too. Ever since a magnetic sense was discovered in other animals back in the 1960s, there’s been interest in whether humans can detect the earth’s magnetic field. Recently a team of scientists at Cal Tech hit the headlines when they showed that our brainwaves react in response to changes in the surrounding field, though we’re not consciously aware of these reactions.

I think it’s too soon to say whether we can actually make use of magnetic signals to navigate, and most modern experiments suggest we can’t. But one thing is certainly clear: some people are much better at finding their way around than others—without the help of GPS, of course. And unfortunately, most of us gradually get worse at navigation as we grow older, even if we remain healthy. People who suffer from Alzheimer’s disease often have much more serious navigational problems.

Those who are naturally good navigators have a different genetic endowment, but a lot depends on training and practice. In a famous study, London taxi drivers were found to have a larger posterior hippocampus (one of the parts of the brain that is crucial to navigation) than other people. This enlargement seems to be a consequence of the heavy navigational demands placed on their brains. And a recent experiment in which millions of people around the world played a specially-designed online navigation game (Sea Hero Quest) revealed some interesting links between navigational ability and social conditions. While men generally scored better than women, the difference was less in countries with higher scores for social equality.

So, it’s quite possible that women have similar innate navigational abilities to men, but are often unable to develop them fully because they have fewer opportunities to practice their skills.

The most impressive human navigators are found among indigenous peoples—like the Inuit of the High Arctic, the Aboriginals of Australia, or the traditional navigators of the Pacific Islands. They can all make long and difficult journeys that most of us would find quite impossible, without so much as a map or compass. They rely on extensive training, often starting at a very early age.

As a sailor myself, I find the traditional Pacific Island navigators especially impressive. To set off in a sailing canoe to make a passage of hundreds or even thousands of miles across the open ocean, relying only on your senses, to locate a small, low-lying island at the end of it is truly astonishing. They employ an extraordinary array of different navigational techniques that take many years to master. They can, for example, set their course accurately by the light of the sun or stars at any time of the day or night, and they can detect the presence of an as-yet invisible island by observing changing wave patterns, cloud formations, and the behavior of birds.

Your book mentions that exercising the navigational skill we possess as humans could help us as we age, and maybe even affect the progression of Alzheimer’s disease. What types of activities do you recommend? What might people of any age who are “always getting lost” do to improve their sense of direction?

Yes, indeed. The parts of the brain that support human spatial navigation also seem to play a key role in other, purely conceptual forms of navigation. They seem to support our capacity for prediction, imagination, and even artistic creativity. So perhaps it’s not surprising that we use navigational metaphors so frequently. We speak of being “on top” of a subject, or “under the weather,” or “mapping a problem,” and so on.

The trouble is that our brain circuits shrink when they’re not used. Now that we’re becoming ever more reliant on our gadgets to solve our navigational problems, this not only means that our natural ability to find our way around is going to decay, we may also find that these other, more abstract but crucial functions are compromised, too. For the same reason, our capacity to cope in the face of Alzheimer’s disease—an increasingly common scourge that attacks the very same circuits—may well be reduced.

So yes, I really do think we should discourage our children (and ourselves!) from becoming totally dependent on electronic navigation. That means turning off the Satnav in your car and putting aside your GPS-enabled phone unless you really need to use them. It means learning routes by taking note of landmarks, and when necessary, plotting your position on an old-fashioned map. Quite simply, you need to start paying attention to everything that’s going on around you, just as people used to do! But I have to admit that it’s going to be very hard to win this battle when arguments of safety, speed, and convenience generally favor the other side.

Actually, there’s another objection to our increasing reliance on these gadgets—they put yet another barrier between us and the world around us. Instead of looking around, noticing where the sun is, or the patterns of stars in the night sky, or which way a river flows; instead of actually working out where we are and where we’re headed, we now just stare at our little glowing screens. We have become passive consumers of navigational information, traveling the world without ever really knowing where we are.

This is a new and dangerous form of alienation. Gadgets can, and do, fail. And there are many places where they don’t work. So just as I would encourage children to admire and respect the living things around them, I would also teach them to find their way around like our ancestors, making use of their sense and their native wits. To learn the “language of the earth,” as Rebecca Solnit has so beautifully put it. It’s not only safer, but a lot more fun!

In reading your book, I felt that you wrote it to awaken people to how awesome the natural world and its creatures are, and to help them see and care about what we will be losing if we don’t take responsibility for the damage we have caused. But not everyone can write such a fine book. In what other ways may those who are aware help to awaken others?

Thanks, you’re too kind! That’s exactly what I wanted to do.

I think the key thing is simply to pay close attention to the world around you and to help others do so, too. It’s especially important to encourage children to observe and respect the natural world in all its diversity, and not to pass on to them any of our silly prejudices. Too often, we only pay attention to cuddly animals like rabbits or koala bears, or glamorous “megafauna” like lions, tigers, and elephants. Of course they are wonderful, but we shouldn’t despise the small and less charming creatures that surround us. I’m thinking of all those extraordinary insects and crustaceans, for example.

I’ve learned so much in writing Supernavigators. I now know that bees, wasps, ants, and lobsters are all amazing navigators, and that some moths have a magnetic compass sense. Dung beetles can use the Milky Way to help them steer a straight course! I look at them all now with even greater admiration than before.

It drives me mad that so many people are willing to give money to save the rhinos, but seem completely unconcerned about the wholesale slaughter of vast numbers of insects and other small but vital and utterly fascinating animals. In fact, they go around spraying insecticides all over their houses and gardens with complete abandon. But that’s a small problem compared with modern industrial agriculture and fishing. These massively damaging and wasteful processes are causing the collapse of entire ecosystems all over the world. Yes, of course we must eat, but our greed is literally going to kill us. We cannot go on exploiting the natural world as if there were no tomorrow.

I’m an agnostic, but I have a very strong feeling of reverence towards the natural world, and, of course, I’m not alone. The great entomologist E. O. Wilson has coined the term “biophilia” to describe “our urge to affiliate with other forms of life.” That’s a careful way of saying that we are drawn to nature in all its wonderfully diverse forms. Wilson is surely right, but what’s more interesting is that there’s masses of scientific evidence that immersion in nature is actually good for us—and conversely, that a life cut off from it is unhealthy. It looks as if one route by which nature aids our health is by boosting our immune system. But I suspect there’s a lot more to it than that. It’s actually something I’d like to research more thoroughly.

More and more, scientists are coming to accept that non-human animals have complex mental and emotional lives, something that those of us who share our hearts and homes with them have long known. They also have capabilities we can only dream of. Why do you think it’s taking so long for people to accept and admit that animals, beyond those we know and love as “pets,” are sentient beings deserving to live fully and are not just here to serve our needs? What can we learn from the non-human animals around us?

Although I’m a believer in the scientific method, I must admit that scientists too have played a significant part in downplaying the abilities of non-human animals. Ironically, it was the desire to gain reliable knowledge that led them to deny what was obvious to most people. It’s interesting that in the 19th century, scientists, including Darwin, often referred to the feelings of animals and took it for granted that they had quite complex mental lives.

But then there was a strong reaction to that kind of “projection.” A kind of minimalism came in that demanded that you adopt the simplest possible explanation of any behavior you observed. Thoughts and feelings were out and behaviorism was in. Animals started to be seen as mere automata that responded only to rewards and punishments, with nothing much else going on in their heads. This view held sway until the 1950s, and it still hasn’t gone away completely, even though there’s now overwhelming evidence that non-human animals are far more interesting and complex than the behaviorists once insisted.

We used to believe that humans had lots of unique “intellectual” abilities that other animals either didn’t have or only had in a very primitive form. Then we discovered that chimpanzees used tools, that parrots and dolphins could learn to manipulate symbols, that crows could solve complex problems, that honey bees had a kind of language, and so on. Franz de Waal has written eloquently about all this. The bastions of human exceptionalism have now crumbled, and it’s clear that even apparently simple organisms can do many remarkable things, like birds and fishes accurately navigating across whole oceans without the help of any instruments.

Then there’s the questions of emotions. Of course, dog owners have been convinced that their pets had feelings very like our own. But it’s taken a very long time for scientists to accept that they were right. Now that the emotional lives of non-human animals have at least become a legitimate subject of research, it’s becoming clear that it’s not just “higher animals” that can think, feel, and suffer, but also many other supposedly “lower” forms of life—like birds, fish, and crustaceans. There are no clear-cut divisions in the animal world between the sentient and the non-sentient. And why should there be? We’re all products of the very same evolutionary processes.

These discoveries have profound ethical implications. We used to grant a special moral status to our fellow humans, largely because we believed that we and we alone shared these special gifts. But how are we to behave towards our fellow creatures now that we know, or at least reasonably suspect, that many of them have similar mental lives to our own? I suspect it won’t be long before most people regard the raising of animals for food in much the same light as slave-owning.

There’s another question lurking in the background: the puzzle of consciousness. Even if we have given up our sole rights to thoughts and feelings, we still tend to think that we alone are truly “conscious.” I must admit I find this a difficult subject to discuss, partly because there are so many problems about defining what consciousness really means. While it’s very hard to assess what it feels like to be another kind of animal, I strongly suspect we’re not the only animals that enjoy the self-awareness and capacity for reflection that are said to be the hallmarks of “true” consciousness. The only thing that definitely sets us humans apart is that we are in a position to influence the fate of every other creature on the planet. And it’s up to us to make the right choices.

How is the ability of animals to freely navigate hampered by human tampering with the environment and landscape, and what can individual humans do to mitigate the damage?

In so many ways, it’s really quite depressing. Let me just offer a few examples.

Pesticides are a huge problem. They not only directly kill billions of invertebrates, most of which are harmless or actively helpful to us, but also deprive many other animals, notably birds and insects, of a vital food source. And herbicides are just as bad. They are laying waste to the food plants on which so many animals depend, either directly or indirectly. The monarch butterfly’s astonishing migration is just one example of a natural phenomenon that’s under threat. The loss of the milkweed plants on which its caterpillars feed, as well as the indiscriminate use of pesticides, have contributed to a serious decline in the numbers of these amazing insects. And insect pollinators like bees are vital to agriculture. If they die off, we’ll be in serious trouble.

What can we do? Well, for a start, we should try to avoid buying food produced with the profligate use of these destructive chemicals. We should lobby politicians to impose restrictions on them. And we should avoid using them around our homes, too.

More generally, the wholesale destruction of the habitats that support so many species of plants and animals, whether by land or sea, is leading to a massive reduction in biodiversity. Think of the rainforests felled to create pasture for cattle, for palm oil plantations, or even just for timber. Or the huge damage caused by industrial fishing, and the loss of coastal wetlands. The bar-tailed godwits that fly from Alaska to New Zealand follow a different route on their return journey, stopping off to rest and feed in the wetlands of China. These wetlands are rapidly vanishing, and this poses a major threat to the migrating birds. Once again, we can all help by making the right choices in what we buy, and also by reducing the volume of new stuff that we consume.

Then there’s climate change. Exactly what the long-term effects will be is impossible to say, but here are just a few examples of what is already happening: We already know that the warming of the oceans is threatening the survival of coral reefs in the tropical seas of the world. These are crucial breeding grounds for many fish and other animals, and their loss could doom many of them to extinction. And changes in the weather are almost certainly resulting in more severe storms and droughts that pose a threat to many migratory birds and insects. Major alterations in the patterns of ocean currents and seasonal winds across the globe, both likely consequences of climate change, will also have huge implications for animals of all kinds, including us.

I could go on and on. What’s clear is that we are faced with a complex set of interlinked problems that we must address immediately if the world we know is not to be changed beyond recognition. Even if our own lives did not depend on the preservation of the almost miraculous biodiversity that makes our planet habitable, we surely have a duty to respect, and protect, the extraordinary variety of living things that surround us. Our present failure to do so amounts to nothing less than vandalism on a planetary scale.

Recently, I saw a TEDx talk given by a young Swedish girl who, at the age of fifteen, went on strike from school to sit in front of the Swedish parliament, protesting the lack of attention being given to the issue of climate change. On the Asperger’s spectrum, with OCD and selective mutism, Greta Thunberg asked pointed questions that demand immediate response: Why, with the seriousness of the climate crisis, are we talking about anything else? Why aren’t we taking action? Why isn’t the imminent danger blasted over the news media? Why isn’t legislation enacted to curtail emissions? Why don’t we change our habits of convenience and do everything possible to forestall the threat? From your own experience and from the interviews you conducted for your book, what might you say in answer to Greta’s questions?

Greta Thunberg is, quite simply, astonishing. There’s something incredibly compelling about her conviction, courage, and purity of purpose. She’s not just another politician trying to win votes. She speaks from the heart. She’s read the science and she knows that something must be done—now—to combat the present and growing dangers arising from climate change.

Why haven’t the rest of us acted? I think there are a lot of different answers. There’s no doubt that vested interests, both economic and political, have taken full advantage of the scientific uncertainties that once surrounded the subject of climate change. Using the very same techniques that the tobacco industry employed successfully when it was first shown that cigarettes caused cancer, they have employed their immense resources to cloud the issues and confuse the public. They have literally bought politicians and news organizations and imposed their views on us, and we have allowed them to get away with it. Never underestimate the power of human greed!

But I also think there is a more profound problem. Deeply embedded in our way of thought is the conviction that we humans are somehow special, superior to all other living things. This world view is of course embedded in the Book of Genesis where it is proclaimed that God created man in his own image and gave him dominion over all other living creatures. In the West, at least, this biblical authority has provided us with a license to treat the natural world as a resource that exists only for our benefit. The results have plainly been disastrous.

Although the Darwinian revolution posed a devastating challenge to this anthropocentric worldview, it still exercises a powerful and dangerous influence. Old habits die hard, and it’s very disturbing that there are still so many people in positions of power who refuse to accept the overwhelming evidence of climate change—sometimes apparently on the basis of their religious beliefs.

Of course, we’re none of us entirely rational beings. We all tend to attach more weight to the present than to the future, and most of us find it hard to resist social pressures. We don’t like to break ranks or take unpopular stands. We also prefer to ignore any evidence that threatens our existing beliefs and seize on what supports them. This is known as “confirmation bias,” and it’s a very powerful influence on our thinking. And we tend to jump to conclusions before examining all the evidence. These flaws in our reasoning processes have certainly contributed to our failure to act more swiftly on climate change.

This is one of the reasons why Greta Thunberg is so extraordinary. She seems to have avoided all of these traps. She has looked at the evidence and grasped its significance. She has focused on the essentials. She has shown exceptional courage in speaking out and taking action when the rest of us have just shaken our heads and hoped that somebody else would solve the problem of climate change.

I find it very moving and encouraging that so many young people around the world are following Greta’s example. Our best hope now is that this brave, angry new generation will force us all to start making the changes that most of us know in our hearts are long overdue.

“We must plot a new course,” you write. If you were to let your imagination run wild, how would you describe this new course for humanity and the planet?

I really think the young are the key to this. People like Greta Thunberg and her followers are capable of changing the terms of the political debate, and there are signs that they are already succeeding in doing so. Once enough pressure has built up, even the dinosaurs of politics will have to change their ways, or they will simply be replaced. It’s true that our political institutions are poorly adapted for dealing with long-term problems, especially those that must be addressed globally. And there’s a lot of simple inertia to overcome. But if things don’t move quickly enough, we’ll be faced with a succession of natural disasters. The danger then is that we’ll descend into chaos, and democratic methods may then be supplanted by authoritarian ones, which would be no fun at all. That’s another good reason why we now urgently need to abandon the “business as usual” approach.

I hope that a new politics is going to emerge, one that is built on the recognition that environmental issues are the key determinants of our future, rather than outmoded, unsustainable notions of unlimited economic growth. As a matter of fact, I’m pretty sure that a world that is taking radical steps to deal with climate change has a good chance of becoming a much more cheerful one, too. We know that the present economic system is grotesquely inequitable and that inequality is already fueling dangerous levels of discontent. Even if climate change weren’t forcing the pace, major changes are needed to ensure that more and more wealth and power are not concentrated into the hands of a tiny handful of people, and that everyone feels they have a voice in shaping the future and a chance to lead a fulfilled life.

The new course we have to set must rapidly lead us away from our present profligate use of non-renewable resources, especially fossil fuels. But more importantly, we need a radical new vision that sees well-being, rather than the accumulation of material riches, as the goal of life. And I don’t just mean physical well-being, essential though that is. I’m thinking about spiritual well-being, too.

This takes me back to what I’ve already said about our deep dependence on the natural world. We don’t just need plants and animals for food. We need them for much deeper reasons, too. Although most of us now live in cities, that is something very new, indeed. In evolutionary terms, the radical shift from a hunter-gatherer existence to urban ways of life has happened in the blink of an eye. As I say at the end of my book Incredible Journeys, whether we like it or not, the deep past still exerts a profound influence over us.

The obvious benefits of city life and modern technology can’t compensate us for the loss of that mysterious something that physical contact with nature alone seems to supply. Perhaps we’re so strongly drawn to the natural world because it is, in some deep sense, our real home—a home to which we long to return. If we are to flourish, indeed, if we are to survive, we must learn to respect and care for the world we inhabit and the extraordinary creatures with whom we share it. If we can all learn this lesson and apply it, then we not only have a chance to fix the problems we face, but also to enjoy lives that are really worth living.

Kristine Morris