Reviewer Kristine Morris Interviews Jeff Biggers, Author of In Sardinia: An Unexpected Journey in Italy

Italy is IT. (No, not its acronym, silly.) Italy is IT!—most marvelous of Mediterranean marvels, spellcaster of bewitchment since the Phoenician days, followed by Greeks, Arabs, Normans, Swabians, Angevins, and Aragonese, all of whom made landfall and said, “IT is ours!” until some other colonizer violently wrested IT away.

Nowadays, fortunately, those IT explorers are more vin than bloodthirsty as they aperitivo in the piazzas of Venice, Florence, Milan, and Sorrento, and wander the glorious ruins of Rome, Pompeii, Paestum, Taormina, and, increasingly, Cagliari and other archaeological sites on Sardinia. Not surprising, once you realize that some of Sardinia’s historic remains date from 1500 BCE, which suggests that the island was the first place prehistoric adventurers from the eastern Med made permanent settlement in all of Italy.

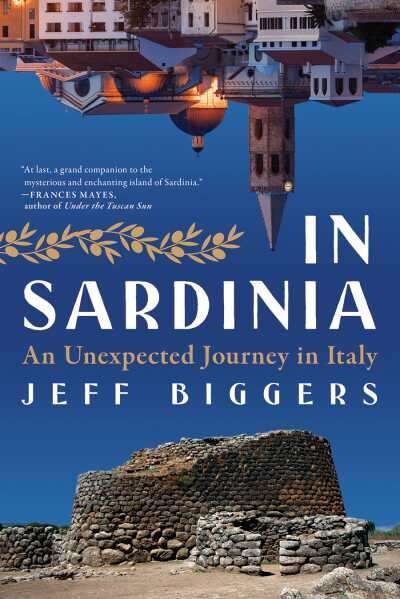

And today’s guest Jeff Biggers says there’s so much more about the island beyond history that warrants your attention—as his In Sardinia makes abundantly clear.

Kristine Morris reviewed the book in a recent travel feature in Foreword and we teed up the following conversation.

Your book is so much more than a travel memoir. It takes a multi-faceted approach to telling the island’s story that includes ancient history, arts and culture, the land and those who inhabit it, and the socio-political environment. What motivated you to undertake this work?

As someone who has lived and traveled in Italy for 30 years, I saw my role not as a “travel writer,” but as a “traveling writer” who could serve as a bridge and translator for Sardinian writers, historians, and storytellers. The island is truly an island of muses, storytellers, and stories. Important historical figures—who have shaped the island, Italy, Europe, and the world—abound with their own stories, including Nobel Laureate Grazia Deledda, political thinker Antonio Gramsci, and numerous writers, artists, and innovators. In all of my years of traveling on five continents, I’ve never encountered such a place of storytelling. But so much remains untranslated for outside readers.

Sardinia as this island of innovation, this nexus of exchange in the Mediterranean, has often been overlooked by travelers and writers—or worse, misinterpreted and disparaged. On the 100th anniversary of D. H. Lawrence’s classic book Sea and Sardinia, it seemed like it was time to reconsider one of the most beautiful places in Italy—and Europe—and open the window for a new view.

Why is the subtitle of your book An Unexpected Journey in Italy? What is there about the place that most surprised or delighted you?

Outside of its fabled beaches, Sardinia is often left off the tour circuit for travelers, including Italians. With the advent of discount airlines in recent years, this has changed dramatically. But travelers often fail to venture beyond the sand and sun of the coast and head into the fascinating interior communities. In 2016, while in Sardinia for a vacation, we made an impulsive decision to pack up our kids and take our 2017 sabbatical in Sardinia. It was the best decision we ever made in our lives. Far from Sardinia being some empty stage of history, as described by various authors in the past, we found an exciting cultural revival and debate taking place, and a treasury of stories amid major archaeological discoveries rewriting the history of the Mediterranean.

Over the next five years on return trips, we sampled the various regions’ famed cuisine and wines, visited the towns and back roads and breathtaking coves and canyons, took part in festivals and rituals, and met with writers, artists, and all sorts of storytellers. We saw firsthand how the vastness of the uninterrupted cycles of civilizations and their architectural marvels, including the “nuraghe” towers from the Bronze Age still standing today, are incomparable in Europe. For example, the only ziggurat pyramid in Europe—the 6,000-year-old Monte d’Accoddi—stands like a runway to another history in Sardinia.

It appears that while some people are enchanted with the island, others are not so keen. What type of traveler is more likely to fall in love with the place, and what do you think keeps others from appreciating it?

While Ancient Roman naysayers like Cicero found all things Sardinian to his disliking, and some grumpy travel writers have nitpicked over some of the inconveniences of rural ways in the past, I dare say today’s modern travelers are more likely to be affected by the “Sardinian blues,” or what Sardinian writer Marcello Serra called “Mal di Sardegna.” When you leave “the island of the Sardinians, with dense memories of fabulous encounters, of landscapes timeless and ancient,” Serra wrote, “then the heart will weigh you down like a ripe fruit.” The problem with visiting Sardinia today is the hardship in leaving it—and the great desire to return.

If you had to describe the spirit of Sardinia and its people in just a few words, what would you say?

“If there is a word to express the feelings of the Sardinians in the millennia,” of ancient times, the great Sardinian writer Sergio Atzeni wrote, “perhaps it is happiness.” Despite invasions over thousands of years, from the Phoenicians to Carthaginians to Ancient Romans to the Goths, Vandals, Spaniards (until Italy’s unification), and contemporary crises over economic development, Sardinia has carved out its own unique ways, cultures, languages, and stories—and altered European history in the process. Such happiness, as a form of resistance, is evident in the exuberance we see in so many of Sardinia’s enduring festivals, processions, and its strong traditions of music, song, and dance. And I’d add beauty, in both the stunning landscape and its colors, from the sea to the Supramonte mountain ranges, and in the people and their cultural ways; Sardinia is rightfully called the “pearl” of the Mediterranean. But there is also another Sardinia—the Sardinia in the forefront of the arts, literature, music, architecture, cultural innovations, political leaders, and more.

You wrote that your time in Sardinia became possible due to a sabbatical, a desire to experience a different part of Italy, and wanting to expose your children to an Italian school system—practical reasons, all. But then something more, something mystical, magical, and unexplainable happened: “The island had its own plans …” you wrote. Please tell us more about this feeling. Did your wife and children have this same experience? Were they as enthralled with Sardinia as you were?

We all—my kids in school, and my wife as an Italian from Umbria—experienced Sardinia in different ways and as we rendezvous back in Sardinia this summer (my older son now lives in Brussels), it appears that the island will continue to remain a point of reference for our family.

Why is NATO still holding military trainings on Sardinia, even having turned pastureland for sheep into shooting ranges, when the island’s people are in opposition? What damages have been done? How are they being remedied? How long might the people have to endure this situation?

Those are good questions, and ones that have been raised in the courts, and continue to be raised in the court of public opinion. Over 60 percent of Italy’s military operations are in Sardinia, including NATO bombing ranges. There have been some breakthroughs—once docked US nuclear submarines have been removed.

What are some of the biggest problems facing Sardinia today?

Like many places in Italy, Sardinia struggles with seasonal work and high levels of unemployment, especially for young people. In a global market, the former economies of pastoral and farming communities, mining communities, and coastal areas, along with the capital city of Cagliari, have struggled over the past decades to shift and adapt. But it’s a long haul.

The island has been a pioneer in online technologies. Not only did Marconi do some of his breakthrough wireless experiments in Sardinia a century ago, but the island had one of the first online newspapers in Europe, and the founder of the island’s wireless company, Tiscali, is considered the “Bill Gates of Italy.” One of the big questions is over the increasing role of tourism, and what many define as the opportunities for cultural tourism: showcasing Sardinia’s extraordinary archaeological and historical sites, villages and events, foodways and wines—as well as how the millions of tourists who come to the island can move beyond the beach to discover the rest of the island and its wonders, and bolster some of the interior economies in the process.

Tell us a bit about Sardinia’s inclusion on the list of the world’s famed “Blue Zones.”

The “blue” in the term “Blue Zones” originates back to the blue check marks made by researchers in mountain communities on the island, which recorded the highest rates of centenarians on the planet. Actor Zac Efron’s top-rated Netflix series, “Down to Earth,” explored the Blue Zone phenomenon of the island, based on the bestselling series of books by Dan Buettner.

Knowing what you know about Sardinia, what might you say to a young person thinking of moving there? A family with children? Digital nomads or retirees?

Sardinia awaits.

What would you most hope readers will come to appreciate about Sardinia after reading your book?

Instead of being on the periphery of empires or an unknown island west of the Italian mainland, Sardinia is central to the Mediterranean story, and a nexus for navigators heading in any direction. In effect, a traveler must first understand Sardinia and its ancient and modern history to truly understand the rest of Italy.

Can we expect another book? Please tell us a little about your next project.

I am working on various theatre, film, and book projects now, but one day I hope to write a similar cultural history and travelogue on Bologna—a city that I’ve called home for decades.

Kristine Morris