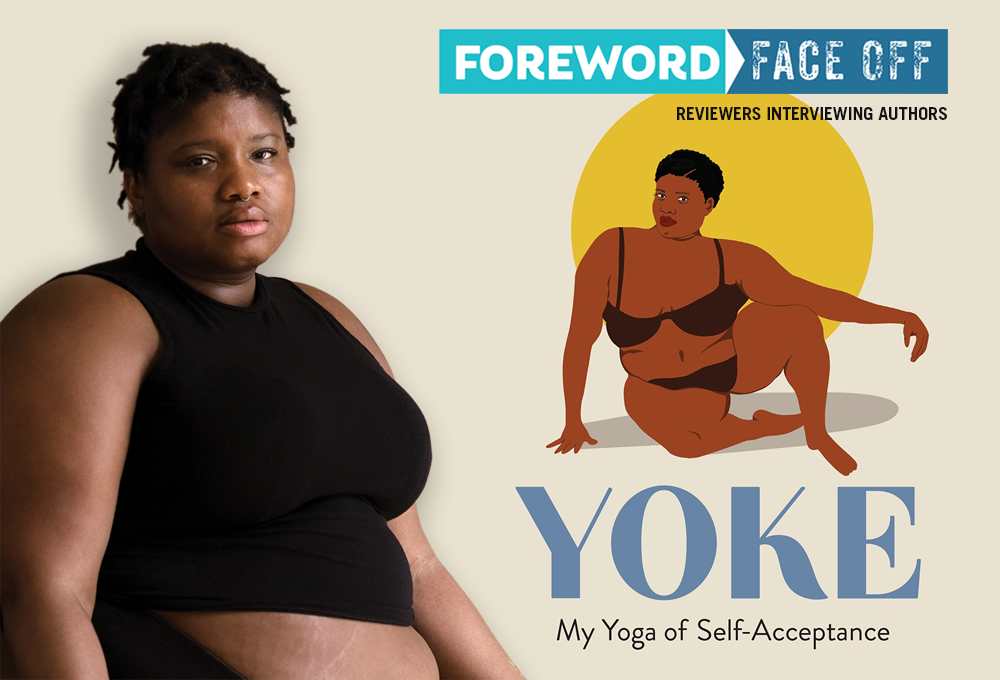

Reviewer Kristine Morris Interviews Jessamyn Stanley, Author of Yoke: My Yoga of Self-Acceptance

If you think of yoga as a rubber-matted playpen for sculpted, silver-spooned soccer moms with surgically enhanced assets, you haven’t met self-described fat, Black, queer Jessamyn Stanley, yoga teacher extraordinaire and author of the recently released Yoke: My Yoga of Self-Acceptance. This week, we’re thrilled to connect our own Kristine Morris with Jessamyn to hear how this unconventional yogi took ownership of yoga through self acceptance, rather than perfect poses.

In her starred review for Foreword’s July/August issue, Kristine admires that Yoke goes far beyond the purview of a typical yoga book because Jessamyn “comes down hard on racism, cultural appropriation, and exalted egos. And those whose yoga consists of trying to be the first in class to master the headstand or win the ‘best yoga wear’ argument will find that this book takes them by the shoulders, stares right into their eyes, and pulls them somewhere deeper. It’s the soul that Stanley’s talking about—the self with a capital s.”

If you’re willing to take a fresh look at yoga, keep on reading.

Yoke: My Yoga of Self-Acceptance, is stunningly honest about your experiences as a fat, Black, queer woman in the mainly thin, White, straight world of American yoga. What was it that kept you going despite how others perceived you, misunderstood you, or communicated their belief that you didn’t belong?

There are few things more liberating than being able to ignore the perspectives of people who do not respect you. I have found other people’s lack of belief in me to be one of the greatest motivators and calls to action.

Right from the get-go, the book tackles “imposter syndrome,” the belief that no matter how things look on the outside, we don’t know enough, could never learn enough, and could never be enough. Do you still struggle with this, and if so, what situations call it up for you?

I wouldn’t say that the struggle with imposter syndrome is a thing of the past for me—any time that I’m a novice at something, imposter syndrome is lurking in the shadows. It helps me to remember that it’s ok to be a beginner, and that it’s not necessary to know everything. Knowing who I am is more than enough. I can be a beginner at everything else.

In a span of ten years or so, you went from practicing yoga in your living room to becoming a “yoga professional,” called upon to practice in ad campaigns for major brands like Adidas and Amazon—a transition that left you feeling conflicted. What was the source of this conflict, and how did you resolve it?

I think my conflict stems from the fact that capitalism and yoga really don’t go together. In particular, social media and yoga are at odds with each other: social media requires that you look outside yourself for answers, whereas yoga asks the opposite. I’m not sure that I’ve really resolved anything, but I have found that there is value in sharing my yoga practice with other people, specifically because it encourages and makes space for other people to live their own yoga practice. In my opinion, if each of us practiced some form of self-acceptance, yoga or otherwise, we’d have the potential for living in a world that navigates from a space of love and compassion as opposed to navigating from a space of fear.

At one point, you wrote, “I need to find a separation between yoga and money because the combination is polluting my soul. I think money and spirituality are generally a problematic combo.” How do you work with this issue in your own life, and can you suggest some ways that others can minimize their inner conflict around charging for spiritual services or teachings?

I think that the practice itself is not something that should be tied up in money. In my own life, I would like for anyone to be able to access my teachings regardless of whether or not they can pay. However, there’s still a need to pay for infrastructure—the resources and people who make my teachings available to others are not free. That is how I rationalize the intersection of yoga and money in my own life. Money is a resource that allows me to do the work that the universe is asking me to do. It is not the final answer, it is merely a tool in the process. It is not the epitome of my self-worth. Beyond that, I don’t know that I have advice for other people. I think this is a very personal journey and everyone’s way of moving forward will vary depending on their own unique yoga journey.

Some may be surprised at your revelation that most of the yoga practiced in the United States differs fundamentally from Classical yoga, especially in the way that American yoga tends to emphasize postural practice over spiritual practice. Why did American yoga choose to emphasize the physical? In what ways might the materialism and capitalism of American culture have influenced this development?

The materialism and capitalism of American culture are the bedrock of American yoga’s focus on postural practice. Postures emphasize the importance of the physical body, and this tracks with the American obsession with faҫades—everything is about how you look rather than how you actually exist beneath the surface.

Your book casts an intriguing light on the power of yoga to reveal “the deepest and most conflicted aspects of the self.” For this to happen, a shift from the drive to master a series of physical postures to a focus on what is really going on within the practitioner is necessary. How did you make this shift, and why did you decide to make self-acceptance the focus of your yoga practice?

I don’t know that I ever consciously decided to make self-acceptance the focus of my yoga practice—it just kinda happened. It feels like it was the natural result of accepting my body and deepening my yoga practice. This then forced me to accept every other part of myself as well.

What is it about yoga, specifically, that makes it so effective in revealing what we might have struggled so long to hide from the world, and even from ourselves? And what about it makes it such an ally in healing inner conflict?

Yoga provides a clear path for uniting the different aspects of yourself. It also makes it very hard to hide from yourself, and to practice yoga for any considerable period of time eventually requires the healing of inner conflict.

You share that you were raised in a devout Baha’i household, but that “Coming out queer shredded what remained of [your] devotion to the Baha’i faith.” What did growing up Baha’i bring to your life that you are still thankful for today?

The Baha’i faith provided me with a strong foundation of values, ethics, and morals which still guide my life. It helps me understand that spirituality exists in all that we do, and that no one owns God—every understanding of the divine is relevant because all human beings are equal. No matter how I feel about the overall nature of religion, I am eternally grateful for this clear understanding of what it means to be a spiritual being having a human experience.

In Yoke, you take a strong stand against “cultural appropriation,” which seems to have become a battleground issues these days. Please tell our readers what, for you, would constitute cultural appropriation, and share any suggestions you might have about how people might celebrate and participate in what’s good and enjoyable about another culture without “appropriating” it.

I think that cultural appropriation is a by-product of the world we live in—it’s what happens when people of different cultures come together. I would argue that it’s almost unavoidable. However, there is a very thin line between appropriation and appreciation, and I think that aiming for appreciation makes appropriation less of an inevitability. Appreciation means learning about the culture and respecting it. Generally speaking, in-depth appreciation provides knowledge that leads to avoiding appropriation. For example, learning the history of Sanskrit and the way it has been used as a tool of imperialism has led me to limit using Sanskrit in my yoga classes.

Appropriation is theft, it’s disrespecting another culture by stealing attributes of it for your personal gain. I think the cycle of appropriation has a lot to teach all of us about who we are as people, and I think that the pain of realizing that you may have offended someone is a very helpful spiritual tool.

Yogic spirituality, you wrote, “is accessible to practitioners of every religious faith.” What would you say to someone who would like to practice yoga, but whose religion teaches against it?

Yoga is beyond religion, and can hold space for all religious beliefs. If your religion is against yoga, it’s possible that your religion does not fully understand what yoga actually is.

You wrote that you used to think of meditation as “more like a lobotomy than anything else,” but that you came to see that it’s for everyone who breathes, that it’s a state of being that turns out to be “the ideal response to every conflict and every moment of doubt.” Please share how you incorporate meditation into your daily life off the mat.

Meditation is a crucial part of my life, and it doesn’t just happen when I’m seated quietly on a yoga mat. Some of my most profound meditations happen when I’m in conversations with other people. It makes it possible to hear and receive other people as opposed to standing in a state of combat. I think that having a mind that moves quickly is the singular prerequisite for practicing meditation. I treat my meditation time as my opportunity to think about everything that I’ve ever wanted to obsess over.

What message would you most like readers to receive from your book?

I would like readers to know that they are enough exactly as they are, that they are allowed to feel their feelings, and that what they bring to this world is absolutely necessary. That no one else can do what they do and bring what they bring, and that they are needed right now, exactly as they are.

Can we hope for another book from you? What might be its topic?

I think my next book might be about parenthood—parenting businesses and parenting children, and the intersection between those worlds. But it’s hard to say right now what the next book will be about. Only time will tell!

Kristine Morris