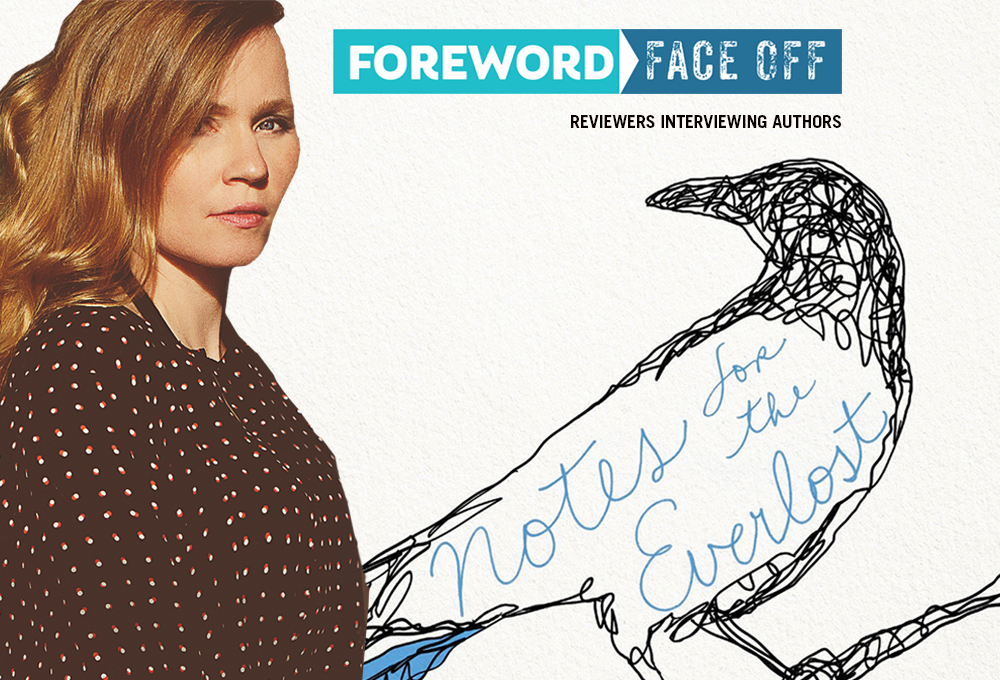

Reviewer Kristine Morris Interviews Kate Inglis, Author of Notes for the Everlost: A Field Guide to Grief

Try as you might to prepare or avoid it, the searing, devastating pain of grief is going to find you at several points in your life and you will be changed by it. But for the length of time it takes to read this interview, set aside what you know and let Kate Inglis tell you about grief from her perspective. She has some experience with the stuff—she lost a son during childbirth, and then her marriage. The heartbreaking story of her experience is shared in Notes for the Everlost: A Field Guide to Grief.

But Kate doesn’t want you to feel sorry for her, far from it. In her mind, grief is an intense expression of love. She says that if we let it become a part of who we are, to integrate it, “we give ourselves the chance to live more fully.”

Kristine Morris, a gifted writer and dear friend of Foreword Reviews, reviewed Notes for the Everlost in our September/October issue. Shambhala Publications helped us connect Kristine and Kate for this extraordinary, emotional, life-affirming conversation.

Your book, Notes for the Everlost, was the most intimate, most profound story of what it feels like to live in the heart of grief that I have ever read. You came to realize that after such loss, there is no real “recovery,” only integration of that loss into a new, different life. How did taking the pressure to “recover” off and allowing yourself to grieve help you? What might you say to the newly-bereaved that would help them give themselves permission to fully grieve and, in time, integrate their loss?

That’s lovely, thank you! The word ‘integration’ replaced ‘healing’ in my lexicon because the practice of integrating felt like a healthier way of facing the absurdity of continuing to breathe in and out after someone we love dies. First, because there’s no such thing as ‘all better,’ like kissing a playground scratch on a four year-old. I wish there were. Getting through each day after loss is an ongoing practice. And second, because the words we use shape us. You can rewire your sense of yourself by choosing better ones.

Western culture rejects grief (and in turn, the grieving)—it tells us to ‘get over it,’ to ‘move on’ and all that bunk. ‘Healing’ sounds softer but sells the same false narrative—that all we need to do is simply put sadness behind us, choosing to move into some cleaner, tidier, magically hopeful next chapter of life. But grief doesn’t cooperate. It’s messy and organic because human beings are messy and organic—we can no more declare we’re over trauma any more than we could declare we’re over stomach cramps or hurricanes.

As soon as you think of grief as a natural phenomenon, you can step back a little to catalogue it. You count yourself among a cohort of unwitting explorers. Rather than judging your ability to perform grief to the arbitrary standards of people around you—compounding the grief by worrying you’re failing at it—you begin practicing being alright with exactly where you are, as you are. In extraordinary loss, you are ordinary! You are normal. This is good. We’ve got to stop thinking of grief as a problem to be solved or a sickness to be cured. Grief is one of our most intense expressions of love. If we let it become a part of the map of who we are—integrating it—we give ourselves the chance to live more fully.

Since we all are likely to experience deep, searing loss at some point in our lives, especially as we age, what might we do to prepare ourselves to meet it? Are there practices you know to be helpful?

We’re never, ever ready. The next time loss happens to me, I’ll be just as shocked all over again. All the enlightenment in the world can’t shield me from that shock. A better way to spend my energy is to actively study how to show up for others with less hesitation. Rather than trying to prepare myself for trauma or loss—time better spent in the garden or the kitchen or jumping through sprinklers—I can resolve to live more gently every day as a more open and attentive friend, lover, parent, teacher (we are all, always, teachers), or student (we are all, always, students).

We should practice being kind, even when we’re afraid—and we’re afraid a lot of the time. We shrink from what we see as the ‘other,’ and we shrink from judgment, and we certainly shrink from grief. The practice is in shrinking less. If we engage in this practice, rather than trying to pre-emptively steel ourselves against our eventual pain, we’ll show up better for each other and we’ll face whatever turns our own story takes with more love.

How did you come to decide to write about Liam’s passing and your grief? In what ways was this difficult? In what ways was it helpful to you? What factors might have made it more helpful?

I started writing in the hospital. It was compulsive. I almost knocked over my IV in the middle of the night trying to find a pen. I knew that to survive what had just happened—regardless of the outcome—I would have to actively sort through the shape of it. I needed to frame what was happening rather than running from it. You can’t outrun this kind of trauma. If we are going to face it, we have to work to see beauty in it. That is what writing does for me.

People have called me courageous for being vulnerable with my writing, but it has never felt that way to me. Some people think it’s brave if we do anything other than keep trauma—being very tender and raw and personal—locked up. But I never felt like I was being vulnerable. Writing made me feel powerful despite having no power over what was unfolding. It was a sorcery. It wasn’t courage that made me write. It was writing that made me feel courageous.

Although we are ultimately alone with our grief, there may be times that we long to have someone be present for us as we mourn. How can we relate to those we know love us but who are unable to be there for us during these times? How might we be more clear about our needs, or even know what they are when the grief is so fresh? Or how can we tell people that we really would rather be alone, or would rather not hear their advice, without destroying the relationship we have with them?

It’s like a tide—when our water is low and distant, retreating, we may need more silence and less companionship. Our thoughts need to be alone with us sometimes. When our water is high, closer to civilization, we may need more chatter, more casseroles, more knocks on the door. I only wish grieving people had a rhythm as easily charted as the tides! It veers back and forth one day to the next, randomly. We may be in one state for hours or months, and then flip to the other and feel either suddenly suffocated or suddenly forgotten, and angry about it.

We are the only authority on our grief. We get to say. Not the peanut gallery. We need the space to state simply how we feel and what we need, without justifying, defending, or explaining it. It’s up to the rest of the world to refrain from trying to negate, fix, shame, or ‘grief-splain.’ Unfortunately, we rarely get that space. Somehow in grief, bereaved people are cast off, belonging to no one, while also being public property against their will.

Bereaved people almost always feel censored by one dynamic or another—by their own guilt and isolation, by other people’s unresolved baggage, by feeling pressure to make a good public performance, by the judgment of others who think we’re not being grateful, faithful, or tidy enough. So we grit our teeth. Every now and then we blow up and speak some truth. Sometimes it makes us feel fierce. Sometimes we regret it. Sometimes the world takes a cue from us, and surprises us by stepping back. Sometimes it doesn’t.

We, both bereaved people and those around us, all just have to keep trying. It’s imbalanced, unpredictable, and full of fear and resistance on both sides. But we have to keep trying. We should always be open to saying, Yikes, this is hard!—it is hard to show up for people wracked by an unimaginable loss. It’s scary. And it’s hard to be that person, an unintentional Medusa. Like a social pox. Rather than saying nothing, let’s have a sigh and talk about how confusing and strange it is to be human sometimes. And let’s keep trying.

In our culture, we are so inept at expressing our care and concern for a grieving loved one. Knowing what you know now, what do you wish those around you had done to be present for you? What acts of love might have brought you support and comfort? Did you find there were different types of support needed for the different stages of grief?

Even if it could be—which it can’t—grief never needs to be fixed. Grief is not the enemy. It can be harmonious and beautiful and full of love. If we demonize and reject sadness, we demonize and reject the sad human being. We deepen their isolation and introduce disharmony. Here’s what we might do: Talk less and listen more. Don’t look at your shoes.

Other than the constancy of people who didn’t turn away, the moments I remember most tenderly are when people responded with outrage that this horrible thing had happened. Those who said THIS SUCKS and THIS IS AWFUL, and with vigor. Being seen and acknowledged by some when others refused was like coming up for air. Yes! It does suck. Thank you.

You’ve created Glow in the Woods, an online community for grieving parents. What inspired this name? Please tell our readers about this community and some of the ways it has been helpful.

Being bereaved—having witnessed death, and especially that of an infant—felt like being lost in dark woods. That desperately, terrifyingly alone feeling. The archetypal turning point in that iconic dream is seeing a cabin with its lights on. We are not alone after all! We might find shelter and company. We might find each other.

I founded the community one year after Liam died, and almost instantly it became the most amazing cohort of voices. It incorporates writing about all kinds of infant loss—stillbirth, SIDS, prematurity and the NICU, medical termination, accidents—and the whole gamut of life after that loss. It’s a place to express how the fundamental core things in our lives have been altered—parenthood, sex, your body, your marriage or partnership, your sense of self, your sleep, self-care, food, spirituality. We recommend books, meet on the discussion board, and offer up practical advice as well as good company.

From the site: “One of us, only half-joking, said this will be a place where us medusas can take off our hats, none minding the sight of all the snakes. Because not only can we bear the sight of each other—we crave it. Babylost mothers and fathers, this place is yours.”

This was our intention, to create the space we had very little of in our lives. To not have to always be in mixed company is such a wonderful thing. To speak plainly about our most raw emotions and have other people chime in and say, “I know that feeling,” is the most visceral, most powerful therapy there is. That we don’t have any easy answers is irrelevant. We are here, and here you are. That’s all that matters.

How did you handle parenting your other children after Liam’s death? How did you manage to give them freedom to take risks, explore, and encounter the world on their own?

What happened to me was as random as a lightning strike. You can’t live out the rest of your life being afraid of the sky.

Liam’s death has informed my parenting in ways that are actionable, and I’m grateful for that. I will do my best to raise boys who aren’t afraid of the sky. Who know how to work through their emotions when they encounter difficulty, who won’t self-isolate, who know how to be a good friend, and how to nurture and give space to others. All I can do is try to equip them for what they will inevitably go through—as we all do—whether I’m here to witness it or not. That is what well-being is: the capacity to be okay even when things are not okay.

Why does grief do such a good job of sifting our relationships so that some fail and others grow stronger still? How might parents give support to each other when their grief makes each of them feel so alone?

Any big moment in life, fortunate or unfortunate, can have a galvanizing effect on relationships one way or the other. Loss is one of the biggest. It shocks us out of autopilot. It’s a great big crisis, a test of mettle.

I’ve had a hard time with this question—staring at it for a while—and I think I just figured out why. It’s the word ‘fail.’ I understand why it’s there—some marriages endure, for example, whereas mine did not. But I’ve got enough distance now to see it differently. Not so much as a failure but as two people who ran one course together, and who may now be running another course together, but re-formed. We are still a family, a team. We still care about each other. Some people remain married but aren’t cohesive at all. Others are uncoupled but care for each other beautifully in a new context. Failure is a concept that’s more about a performance than authentic well-being. It serves us well to think differently about it.

The advice I’d give people seeking to keep any relationship intact through loss—romantic partners, family members, friends—is the same, if being intact is what you need. If you’re the one who’s struggling, don’t try and vanish the struggle. Let it get some air before it goes gangrenous. And if you’re the one who currently feels steady on your feet, don’t turn away from an ugly or scary bit of pain trying to get some air. Please don’t. And don’t try to fix it, rush it, or diminish it. Don’t make it about you. Just let it be, and be patient. Show up with whatever might help your loved one try again tomorrow. Let what you know of that person—what helps them be their best self—inform how you respond to them every day, with fresh air and distraction, crowds or silence, activity or hibernation. Treat their nightmares with as much sacred respect as you treat their dreams.

From where you are now, how are Liam and all that happened with him integrated into your life? How have his short time on this planet and his passing changed you from the person you were to the person you are now?

Liam changed me in every possible way, from every angle. Like how we shed skin cells and never stop—how we are never the same physiologically—knowing him was rapid erasure and reformation of every part of me. I’d rather have him with me and be a little more fortunately dull, a lot more oblivious. I would never have chosen his loss as the means for this kind of insight. But if this is what my life is to be, what else can I be but grateful for it?

What message would you most like to send to bereaved parents? And how can the rest of us help?

I want bereaved parents to know there’s nothing they need to do other than be where they are, because where they are is normal and rooted in the most ancient love. The rest of the world can help them by making sure they know it.

Kristine Morris