Reviewer Kristine Morris Interviews Katharine Norbury, Editor of Women on Nature: 100 Voices on Place, Landscape, and the Natural World

Shame on all you nebulous, all-purpose words—having sacrificed your uniqueness, what do you have now that your true meaning is lost to the ages?

Take “nature,” that most lovely of ideas now defined to exclude humans and things created by humans, as if we don’t belong here on Earth. Well, we want back into the club, dammit. Don’t deny us our kinship with brother grizz and mighty oak.

In the interview below, Katharine Norbury mentions that “nature” causes her mixed feelings precisely because it “separates us from the rest of planet’s inhabitants, morally and practically.” Moreover, she says, “Referring to ‘nature’ as ‘other’ removes us from feeling responsible towards it.”

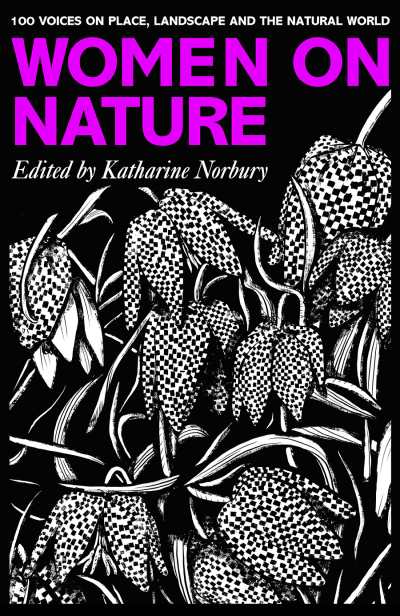

Katharine is the author/editor of Women on Nature: 100 Voices on Place, Landscape, and the Natural World, which recently earned a starred review from Kristine Morris in the pages of Foreword. With the help of the good people at unbound, we busted a tail to set up the following conversation.

What inspired you to create this beautiful and wide-ranging anthology of women’s writings on nature?

What has come to be referred to in the UK as “nature writing,” or even “new nature writing,” has come to be associated with white, and for the most part privileged, men. Although women’s writing on the topic has begun to emerge in recent years, there is often a certain similarity of tone, subject, “voice,” if you like, as if those women (and I may well be one of them) were in some way emulating their established male counterparts. Novelist and nature writer Melissa Harrison has written that “the knowledge of a genre’s make-up can alter people’s creative practice: I have felt the pressure to be more ‘male’ in my work (which I perceived to mean more objective, and less personal), and at one point I even considered writing as ‘M.Z. Harrison’ and concealing my gender entirely—something I’m very glad, now, that I didn’t do.” I understand this sentiment and wanted to push against it.

Interest in writing about the natural world really took off in the UK in 2008, when Granta published a collection called Granta 102: New Nature Writing, and I wondered what would happen if I went back as far as I reasonably could and searched for women’s writing in English about the natural world in the islands of Britain and Ireland. I wanted to locate writings by women who weren’t aping male writers, and who didn’t think of themselves as “nature writers,” because “genres” as such didn’t yet exist. By moving forward from this different baseline, I suspected a different trajectory might emerge.

Please tell our readers a bit about your background.

I grew up in “sub-ruria” about twenty miles from the once-great port of Liverpool, where I was born. The England of the 1970s saw the rise of a rash of new towns and housing developments, and my family lived in one of these that had been built on a Norman village. These new towns were accompanied by “green belts” of conserved farmland, and my friends and I could walk through a brand-new housing estate into ancient bluebell-filled woodland in a matter of minutes. Walking on, we’d come to green fields where black-and-white cattle grazed against a backdrop of industrial cooling towers and distant petrochemical plants streamed plumes of toxic clouds into otherwise flawless skies. The deeply rural and the heavily urbanized were inseparable from one another.

My father, a professor of mechanical engineering at the University of Liverpool, and my mother, who led the Girl Guides, both loved hiking, camping, and the “outdoor life,” and they passed these passions on to me. We always spent our summers among the mountains in Scotland and the English Lake District, and these landscapes are etched into my psyche.

In your introduction to Women on Nature, you mentioned having had feelings of discomfort with the concepts of “gender” and “nature,” having been brought up to give little regard to gender differences, and always having felt connected to the natural world. How did you reconcile these concepts in your own mind, and have your views on each changed since working on the book? If so, how?

Both “gender” and “nature” are now deeply politicized terms. Having been raised to think of myself as gender neutral, if I bothered thinking about it at all, I’ve been forced to engage with the reality of the disparity of opportunity available to people of different races, ages, genders, levels of education, and economic status. I would rather focus on the things we have in common, rather than on the characteristics that divide us. I see this anthology of women’s writing as an opportunity to look at things from the perspective of the slightly-over-fifty-percent of the population who are least credited with shaping our cultural and economic landscapes.

My feelings about “nature” are equally ambivalent. When I began working on the book, I agreed with the philosopher Timothy Morton that the word “nature” was unhelpful, simply because it separates us from the rest of the planet’s inhabitants, morally and practically. Referring to “nature” as “other” removes us from feeling responsible towards it. But of all the species, humans can be singled out for our sheer capacity to destroy anything and anyone that stands in the way of our drive for short term gain. I find it very easy to imagine that the world would have a better chance of survival without us.

When I approached the anthology, I tried to set these thoughts aside and instead observe the way women writers have situated themselves within the natural world. “Nature writing” is often associated with environmentalism or natural history, but by including the more domestic interactions of women writers with their landscapes, I developed a better sense of both our responsibility and our agency towards that which sustains us. The fourteenth century anchorite Julian of Norwich refers to gardeners as having the most important job of all. This individual sense of responsibility, of being able to care for that over which we have immediate control even if it’s just a window box of bee-friendly flowers, makes the overwhelming panic over the climate crisis feel more manageable. Taking charge over what we can brings “radical hope,” a sense that change is possible through a thousand tiny micro-actions.

Along with your writing and work in film and television, you also teach undergraduate courses in writing about “place.” What attitudes toward climate change do you see among your students?

There is a great deal of anxiety and fear among the current crop of students, and this anxiety increases every semester—it’s a normal, healthy reaction to a deeply unsettling global state of affairs. The fact that adults have been so slow to respond to the climate crisis, and to societal and racial injustice, cannot fill them with much hope. We used to look up to our elders. Now there is a sense that the young are on their own. Having said that, the young people that I meet are also deeply resilient, sensitive to the biases ingrained in our societies, generous in spirit, unafraid to question inherited mores, and have a deep sense of fairness. There is great hope in this.

How did you decide which writings to include in the anthology?

I looked for any reference to the natural world in the writings of women, things like how to identify field mushrooms in a nineteenth century book on household management; an imaginary dialogue between an oak tree and the man cutting it down in a seventeenth century country park; a twenty-first century account of a foot-and-mouth disease outbreak on a sheep farm. I wasn’t avoiding the ecological crisis, it’s there if you look for it, and can be seen in the work of Sally Goldsmith or Nicola Chester. But I was listening for something specific, like the sound of underground water. Connection, I think, and observation. Connection with the other inhabitants of this precious universe: animate, inanimate, rock, stream, snow, shore, star, forest, moth, bee, fox.

In your introduction to the book, you mention that it’s “a collection of writing by women about the experience of being under a permissive sky rather than beneath a manmade ceiling.” How has that ceiling, “usually made by a man or men,” affected your life and career? How do you handle the efforts, overt or covert, of a patriarchal system to impose limits on your freedom to live and work as you see fit?

The “downsizing” that happened in the 1990s brought my “job for life” at the BBC, with its comfortable salary, pension, annual leave, sick pay, and maternity leave to an end. I doubt that it was a woman who thought it was a good idea to create a vast force of freelance people who will have inadequate provision for their twilight years and who are controlled by anxiety over the precariousness of their situation: living from one contract to the next, hand-to-mouth, indefinitely. The same has happened in academia. I always laugh when I see the page of a contract that says, “Benefits. There are no benefits.” I imagine it was men who thought that up.

Trickle-down economics has become “stop-up-the-gaps” economics, so that nothing trickles down. The “haves” benefit tremendously, while the “have-nots” (and creatives and makers are, for the most part, have-nots) are left to make do and somehow get by. The present state of affairs in publishing is such that never-before-seen profits are being made by investors, while writers must share less of those profits between them. We are living through what Mark Carney, former governor of the Bank of England, has described as “the steady downloading of risk onto the shoulders of individuals.” I am one such individual. It goes without saying that women, who make up the greater percentage of care-givers of their own infant children or aging relatives, and those of others, are unfairly disadvantaged by this system.

You wrote that “it is our species that has the capacity to act, consciously, for the good of the whole. To act, to conserve, to change, to renew, to invigorate that which we encounter, not merely to observe and catalogue its fall.” What do you think stops people from taking action? What do you think it will take for people to realize what’s at stake? What might appropriate and effective action look like?

The naturalist Jane Goodall has said that what separates us from the great apes is our linguistic ability. However, I suspect that it’s our linguistic ability that enables us to describe concepts that we are currently unable to process. It’s all too abstract, too apocalyptic. We need concrete images. For example, in parts of China there are no longer any bees, so fruit trees are pollinated by hand by people with paint brushes and little pots of pollen. Can you imagine that happening in the USA? Yet one in every three mouthfuls of the food we eat is pollinated by bees or other insects. We need to stop using insecticides and pesticides in our back yards and learn to be happy with a little wildness. We need to make changes in our own lives. How about stopping the use of plastic? Go back to brown paper bags and waxed paper. We managed fine without plastic until about forty years ago!

We must learn our proper place and start inhabiting it. Quickly. We should ask why so many people are on the move. What is the refugee crisis really about, and how much of it is caused by degradation of habitat, rising temperatures, loss of water supply, and the ensuing societal breakdown? When we don’t address these issues, what is gained and what is lost are far from equal.

We have much to learn from Indigenous communities, and from the ancient Celtic tradition of the “wise woman.” The spiritual path is another way into thinking about our place in the Universe and our responsibility towards our common home. The Abrahamic religions have been fantastically slow to wake up and smell the coffee, although the Greek Orthodox Church has had a deep interest in the natural world for a long time. But in general, they’ve all been pretty low-key in shouting out the message.

What do you feel is the role of a writer in all of this?

The role of a writer is to reshape the narrative to make the future both comprehensible, accessible, and also possible by showing us where we fit in. By showing us how we belong. That this is our story—it isn’t just happening to other people far away, or if it is, it’s getting closer very quickly.

In what ways do you see the voices of women as being particularly relevant for our times?

I grew up in the 1970s enjoying the full fruits of my forebears’ fight to ensure I had a vote, an education, and the right to live my life as I saw fit. I accepted all these things as my birthright and never questioned them. I was a product of my time. I was raised to believe that all human beings were equal. While I had noticed that there were no women priests, I imagined it was only a matter of time before the priesthood would be opened to them. The Church of England ordained its first women priests in 1994. In the Roman Catholic Church, women are still waiting. In the last few years, I have watched as girls and women all over the world have been stripped of their rights, have seen their religious freedom and education curtailed or stalled, their life paths proscribed by male relatives and lawmakers, and their voices hushed. Making sure that the voices of women are heard has never been more vital than it is today.

Of all the marvelous writings in Women on Nature, which are your particular favorites, and why?

Oh, what a difficult question! All the pieces have their special qualities. I have been bowled over by the poetry of Dorothy Wellesley, a wonderful observer of the natural world whose work has been out of print since the middle of the last century. I am quite taken with Hannah Hauxwell, the uplands farmer who lived without electricity or running water until the 1970s; the writings of the English mystic Evelyn Underhill; and the “sub-rural” writing of the late Deborah Orr. And Irish writer Keggy Carew’s piece on becoming a “river monitor” in a patriarchal world of hunting and fishing leaves me in stitches every time I read it.

Can we hope for another book after this one?

I have been working on another book, quietly, in the background of Women on Nature. I find it hard to talk about writing while I am doing it, perhaps out of superstition, or more likely a fear that if I articulate my ideas anywhere other than between the pages of the work in progress, it will elude me like candlelight in sunshine, and I will lose sight of it. Suffice it to say that it’s about a journey, or, the idea of the journey, and that it’s located, as was my first book, The Fish Ladder, in the extremities of the island of Britain. At a certain level, it’s about pilgrimage. Perhaps all my work is about the idea of journeying in the hope of discovering something, even if it is simply a different perspective.

Kristine Morris