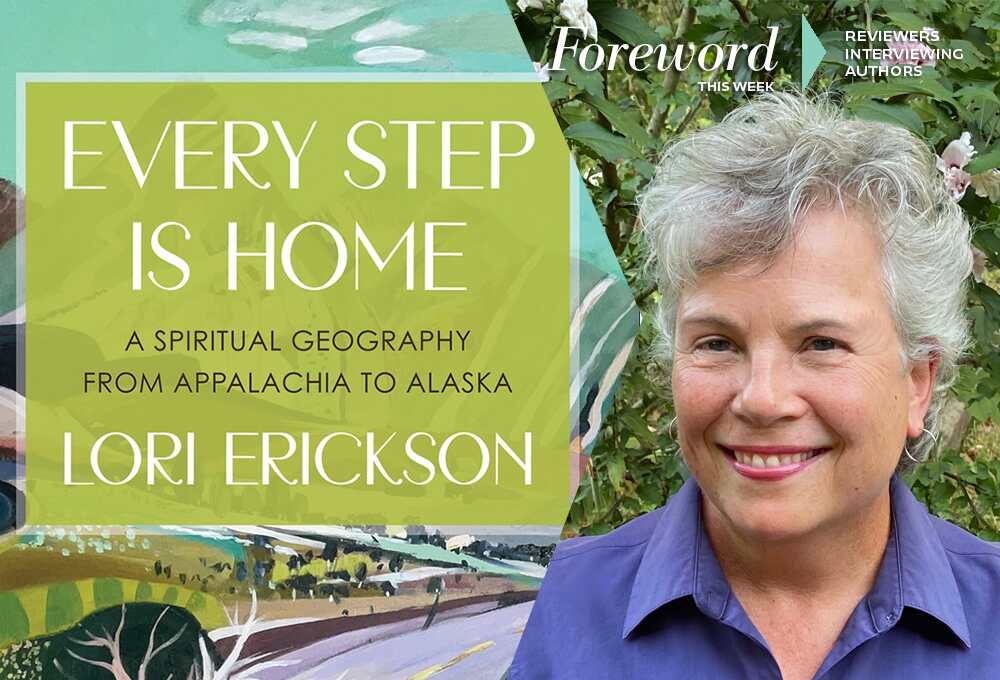

Reviewer Kristine Morris Interviews Lori Erickson, Author of Every Step is Home: A Spiritual Journey from Appalachia to Alaska

What makes a place holy?

You do. Holy is wholly personal.

This week, Lori Erickson reminds us of this sacred truth. She points to the Celts who believed there are places where the veil between our world and the spiritual world is thin. And if we are attuned spiritually, we instinctively gravitate towards them—whether it’s Notre Dame Cathedral or a grove of aspens on a riverbank.

“My own personal shorthand is that if my eyes well with tears, it’s most likely a sacred place,” she says.

Over the years, Foreword has reviewed three of Lori’s earlier books, and when Every Step is Home: A Spiritual Journey from Appalachia to Alaska arrived recently, Kristine Morris accepted both the review and interview assignments.

Your book’s title is a moving reminder that wherever we walk on this beautiful, fragile planet, we are at home. After global travels, you’ve chosen to focus on holy places in the United States, honoring nature and reminding us that everything—the air, water, soil, stone, fire, and light—is sacred. When did you first come to know this, and how has this awareness formed and shaped the person you are today?

I grew up on an Iowa farm and spent a lot of time on my own as a child. Our woods were my playground, a source of solace, and the place where I daydreamed and reflected. I remember reading a lot of books on Greek mythology and how I loved the idea that some places have spirits associated with them—sacred springs, rivers, trees, etc. I imagined that spirits like these lived in my woods too. So, thinking of the natural world as sacred goes back to my earliest memories.

Then I married a man who loves to camp and hike, and after our sons were born, we spent part of every summer camping, mostly in the Rocky Mountains. If you added it all together, I’ve probably spent three years of my life on camping trips, in addition to many other experiences in nature.

These experiences have been central in shaping my heart and soul. From the time I was very young, I’ve always looked to nature for sustenance, comfort, and inspiration.

In the book’s introduction, you wrote that you seek “connections to the sacred that transcend religious differences.” How does being an Episcopal deacon leave space for your deep appreciation of other spiritualities? Do you combine elements from them in your own spiritual practice, and if so, what effects have you found as a result?

In my book Holy Rover, I wrote that I like to think of myself as being in an open marriage with Jesus—we’re both free to see other people, but at the end of the day we always come home to each other.

That book explores my winding path through many faith traditions (including Wicca, Buddhism, and Unitarian Universalism), and my eventual decision to become a deacon in the Episcopal Church. I consider my life proof that God has a keenly developed sense of irony. Fortunately, the Episcopal Church is a good match for someone like me. I appreciate being part of a tradition with deep roots and beautiful rituals, while still being open to inspiration from other faiths.

I think the world of spirituality is a bit like a hardware store, in that it has lots of useful tools. A cordless drill isn’t good in every situation, but when you need it, there’s nothing more useful. The prayers and rituals that I’ve experienced on my travels often get tucked away in my spiritual toolkit, because I never know when they’ll come in handy. One example is that after researching my book Near the Exit: Travels with the Not-So-Grim Reaper, I developed my own version of the Mexican Day of the Dead. I also have a meditation practice influenced by Buddhism. In Every Step is Home, I shared how my home altar contains a bear skull (people will have to read the book to find out why).

What is it about sacred sites that makes the holy palpable? How is the experience of them different from the experience of a magnificent view, or from visiting the site of a meaningful historical event? What is it about them that makes people want to call them “sacred?”

In my books I try to convey that sacred places come in many forms. What’s holy for one person may not be so for another, though there are certainly places that are widely recognized as being set apart in some way. Sometimes they’ve been hallowed by the prayers of people over many centuries, as in cathedrals. Or they’ve been made sacred by tragedy, such as a battlefield. They’re often connected with someone of remarkable spiritual radiance, as in Assisi, Italy, the home of St. Francis. And sometimes they’re places in nature that fill us with awe and a sense of wonder.

My own personal shorthand is that if my eyes well with tears, it’s most likely a sacred place.

What was your first experience of travel to a sacred site, and how did it affect you?

As an adult, the first holy site that deeply resonated for me was Bear Butte in South Dakota (which I wrote about in Holy Rover). My husband’s family lived nearby, and every summer when we visited them I would climb Bear Butte. It’s long been a sacred site for tribal nations that include the Lakota and Cheyenne, and as you walk you see many prayer flags tied to the trees. I was moved and intrigued by the way that starkly beautiful peak is adorned with visible indications of people’s search for the sacred.

Given who you are, and what you’ve learned about experiencing the sacred outside the four walls of a church, what might you say to someone who decides to stop attending church and instead spend more time in nature? Can we combine church and nature for a deeper, richer experience of the holy? Might nature-focused spirituality seem threatening to mainstream churches?

I wouldn’t say that most mainstream churches are hostile to nature-focused spirituality—it’s just that it’s not on their radar very much, although almost all of them have summer camps in lovely natural settings where kids spend a lot of time finding spiritual meaning outside. But then those kids grow up, and that connection to the outdoors fades. Spirituality once again becomes something you do inside four walls. I don’t see it as an either-or, that you’re either part of a faith community or you find spiritual meaning in nature. It’s more yin and yang. One feeds the other.

Speaking personally, I think it’s hard to sustain a spiritual practice as an individual. We are hardwired to need community, and churches are generally good places for that.

How does your experience of the holy in a great European cathedral compare with what you felt at the small chapel of Chimayó in New Mexico or Indigenous holy sites in the US? What is it that makes a place “sacred?” And how do we distinguish between an encounter with the “holy” from the appreciation of natural or human-made beauty?

I love holy sites in all their many varieties, from grand cathedrals to small chapels, from the Grand Canyon to a sacred spring. That said, the moods in each can be very different. When you’re feeling vulnerable and grieving, for example, one place may speak to you and another will not. That’s why we need many types of holy places.

As for what makes a place sacred, I think one of the best descriptions is from Celtic lore: there are places where the veil between worlds is thin. We naturally gravitate to these “thin places” when we’re on a spiritual quest.

I don’t make a big distinction between a holy site and an appreciation for beauty. They’re so intertwined that the distinction doesn’t make much sense to me. A work of art can be as awe- inspiring as a cathedral or an incredible vista in nature. The spirit flows through many vessels.

Of all the places you’ve visited and researched, which gave you the most memorable experience, and what was it about the place that moved you so deeply? Do you consider your travel to sacred sites a pilgrimage? Why, or why not?

Well, asking me to name my favorite holy place is like asking me which is my favorite child. But among my favorites are Ephesus in Turkey, the Temple of Philae in Egypt, the Serpent Mound of Ohio, and Machu Picchu in Peru. These are all places that moved me deeply in ways that are hard to express. They made me want to be silent and still.

I consider all my travels to sacred sites to be pilgrimages, which I define as a trip that changes you. A pilgrimage typically requires advance preparation and is as much about the journey as the destination. And once you return home, you usually need to spend a long time pondering what you experienced. That’s one of the things I appreciate about my work—it gives me the chance to think about my travels more deeply, because you can’t write about something without spending a lot of time turning it over and over in your mind.

It’s interesting to me, as a visual artist, to see how humans in the grip of a spiritual experience so often respond by making something: a pile of stones, cave art, paintings, songs, a towering cathedral, and in your case, books. What are your thoughts on the linkage between the spiritual experience and the urge to create?

You have hit upon the topic of my next book! I’ll be spending the next few years pondering this very question. Can I give you a response in about three years? ;)

It’s unthinkable that anyone would ever propose leveling Notre Dame Cathedral to put in a housing development or shopping mall, yet Indigenous holy sites haven’t always been granted the same respect. What makes it possible for people to remove remains and artifacts from ancient burial sites, and call it “progress” when pipelines are run through sacred lands? Someone once asked how a non-Indigenous person living today might feel if their great-grandmother’s remains were taken from a cemetery and put on display in a museum! What are your thoughts on the way the US has treated Indigenous sacred lands, burial sites, and artifacts, and to what degree is this changing?

I agree that Indigenous sacred lands have far too often been sadly neglected, desecrated, and destroyed. But I also think that this cavalier disregard is slowly changing for the better. For example, the sacred sites I feature in my new book, including the Serpent Mound, Chaco Canyon, and Effigy Mounds, are all protected by public entities that work in partnership with tribal nations.

I’ve included these Indigenous holy sites in my book because I hope that people will be curious to learn more about them and want to visit them. Right here, in the United States, we have spiritual treasures as remarkable as those in Rome or Jerusalem.

If you were to create a “sacred site” today, what would it be like?

I have a home altar, so that’s a sacred site for me personally. But a public sacred space? I think there are many ways to create one. Construct a labyrinth for walking meditation. Build a beautiful, serene chapel with windows that overlook the sea. Restore a prairie or a patch of woods and put in benches for people to sit on and reflect. Create or commission a work of public art that invites contemplation.

I think the holy is just waiting to sneak in under a door or through an open window. We just need to give it a little help sometimes.

If a novice at traveling to the world’s holy places came to you for guidance as to where to go and how to prepare spiritually for such an adventure, what would you suggest?

I’d tell them to read my books (cough, cough). And then listen for a call, which might come in the form of an overheard conversation, or a podcast, or a casual conversation with a friend. I think when the pilgrim is ready, the path will appear, to paraphrase an old saying.

Please tell us a little more about the new book you are planning, and why its topic draws you.

I’m hoping to do something about spirituality as channeled through human hands—in short, about art as a vessel for the sacred. I want to spend the next few years looking for inspiration in various forms of art, from architecture and music to dance and the visual arts. Part of my reason is that during the pandemic I started taking online art classes and dabbling in sketching with ink and watercolor. As amateur as my efforts are, they’re helping me see the world in new ways and have made me curious to learn more about how other people have used art as a way to channel spirit.

Kristine Morris