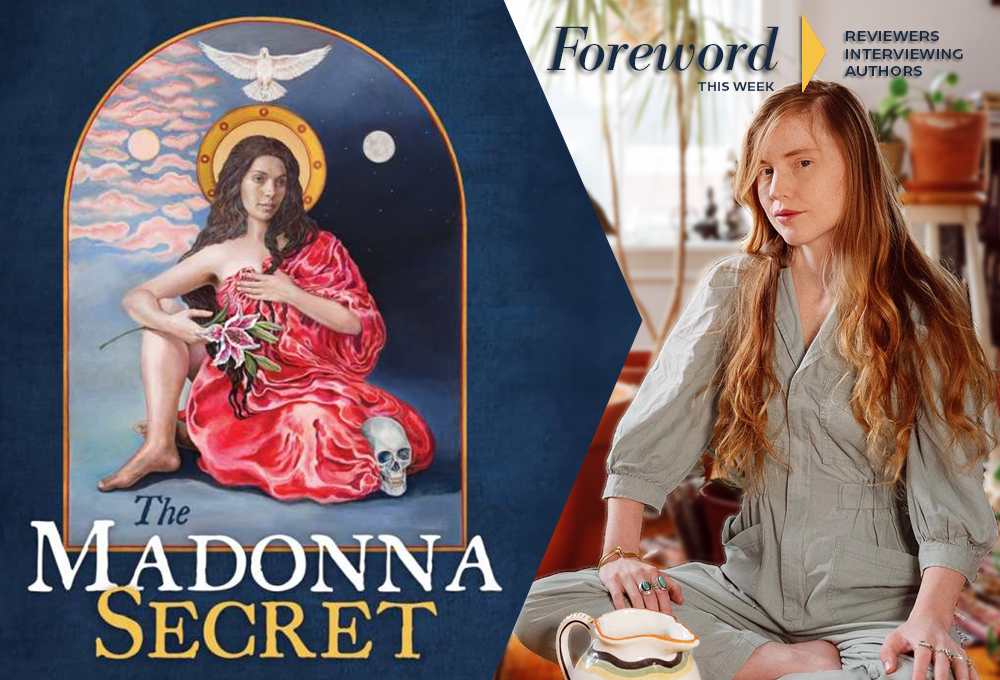

Reviewer Kristine Morris Interviews Sophie Strand, Author of The Madonna Secret

Our homo sapien habit of putting a human lens on the motivations and characteristics of other beings—anthropomorphizing—takes a strange twist in the case of Jesus, where the opposite happened. For hundreds and hundreds of years, his followers and the Christian powers that be portrayed him as more God than guy. They basically neutered him of his manliness.

Let’s call that disanthroprophetizing—taking the man out of the prophet.

But doesn’t it seem unlikely that a genteel, slightly built, ascetic figure could inspire such an enthusiastic following under brutal Roman occupation?

Sophie Strand certainly thinks so. In her mind, Jesus must have had “enormous physical vitality and kinetic intelligence.”

No, Sophie says in the interview below, you can’t just be a prophet and a storyteller to do what Jesus did, you have to be “a physical genius, able to tell stories that you know will agitate your audience into interruption and anger, and then to control and win over the crowds.”

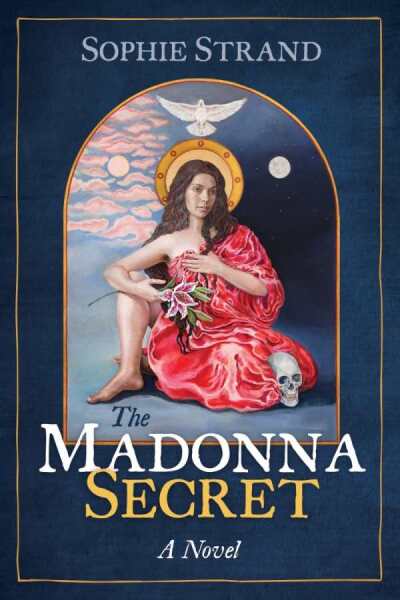

And that’s the Jesus you’ll find in The Madonna Secret, a spectacular reimagining of his relationship with Mary Magdalene, as well as the complex religious culture of the Second Temple Period in Judea and Galilee. But foremost, this is Mary’s story, and Sophie grounds her in earthy mysticism, with great healing powers of her own. Furthermore, she and Jesus burn with passion for each other and Sophie doesn’t shy away from their sexual relationship.

Sophie may not have been facing a Roman legion, but it takes some serious nerve to take on the Jesus story—consider us awestruck.

Kristine Morris honored the book with a starred review in Foreword’s September/October issue, and made the most of her chance to ask Sophie a few questions.

Your portrayal of Miriam, whom many call “Mary Magdalene,” counters the story that she was a prostitute, showing her to have been an educated woman, born into wealth, and a powerful healer, as well as a clear-eyed visionary who was able to see the fate to which Yeshua, the man she loved, was being led by those whom he considered loyal friends. What do you think might have happened, and where might your book have taken us had Miriam’s warnings been heeded?

Coopted by empire, translated into the language of his murderers, most of Jesus’s teachings and stories have been sanitized of their anti-hierarchal, ecologically radical wisdom. I have to wonder if, like a plant, they would have grown hardier, mores resistant to misinterpretation, had they been given more time to mature and grow. His ministry was incredibly short—just three years—and his teachings were in the earliest stages of diverging from other popular Jewish movements of the time period.

I have to imagine, had he heeded Miriam’s warnings, he would have bought himself more time to develop his particular style of interruptive pedagogy: telling riddles and stories that agitate people into dynamic conversation that question dominant paradigms. Initial followers, inspired by greed and visions of power, may have been diluted by a growing group of people who more fully embodied his inclusive vision. How much deeper would his teachings have been if he had been allowed more years to refine his beliefs?

Other than the unfortunate portrayal of her as a prostitute, what references show her to have been more like the strong, gifted woman portrayed in your book? Where did you find convincing references on her having been Yeshua’s wife?

We can date the unfortunate conflation of Mary Magdalene with the unnamed “sinner” woman of Luke to a particular sixth century sermon given by Pope Gregory. The first two hundred years of the Christian movement encompass a biodiversity of “Christianities,” many of which centered on female leaders and teachers. As Christianity became the figurehead of Rome and empire, its ability to center the disenfranchised, outcasts, and women, was seen as a direct threat to the ways in which it operated with systems of domination.

Many scholars and feminist theologians, including Meggan Watterson and Margaret Starbird, have argued that Pope Gregory was consciously trying to undermine the figure who offered the alternative, competing view of Christianity as an egalitarian, anti-imperial movement. The past hundred years has seen a resurgence of scholarship focused on early Christianity and texts deemed heretical in the centuries where Rome was concretizing the Christian narrative. Paradoxically these texts predate the synoptic gospels of the New Testament and may provide a clearer vision of the historical Jesus and his followers. Taking this into account, it is striking to see that the Magdalene is highlighted as a teacher and special companion of Jesus in many of these documents.

Why is it that patriarchy has been able to hold its grip on the world for so long, and why has there been so little revolt against it on the part of women?

I am loathe to place the blame solely on patriarchy when what I see is a bigger systemic issue: a paradigm of separation and domination that gains traction sometime after the Bronze Age Collapse. As demonstrated in the work of Riane Eisler, following the Bronze Age Collapse, we see in the Middle East and Europe a movement away from nature-reverent partnership cultures whose art and religious iconography focused on plants, animals, and festivity—never depicting death or heroic individuals—into an age of hierarchical city-states with heroic figureheads that asserted their power through violence. Women and men alike have revolted against these paradigms time and time again and have been eradicated by a system that is built to do just that: kill and eradicate.

Dionysian priestesses, inspired by a pre-Olympic god of liberatory festivity and anti-imperial mayhem, inspired the two almost successful revolts against the Roman Empire: that of Spartacus and Paculla Annia. We must also call to mind the words of feminist Audre Lorde who advises us, “The master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house.” Every piece of folklore, herbal wisdom, and midwifery magic that has been passed down orally, pressed from breast to breast, is an antidote to the violence of empire. It is a sideways revolt. Violent revolts against dominator cultures tend to fail and then get written out of the biased historical accounts we receive. But the true revolts do not use the master’s swords or tools or violent outburst. They are stories, secret circles, the tenacious ability of the marginalized to keep their wisdom and narratives alive in boats of breath.

What gave you the courage to portray Yeshua as a strong, vigorous Jewish male in the prime of life rather than as the pale, ascetic, Europeanized figure to which we’ve grown accustomed?

What does it take to get control of an audience? Now imagine that audience is made up of people who have been oppressed by empire for thousands of years. People who have had the land where they buried their ancestors seized on the sneaky premise of bad loans by the Romans. People who have seen their relatives crucified after revolts. People who do not have land to farm to feed their families, forced to slave as dayworkers to produce wine and grain for the people running the empire that is killing them and making a joke of their religion and God every day.

What does it take to command the attention of people like that? I think it takes enormous physical vitality and kinetic intelligence. It means you are more than just a prophet or a storyteller. You are a physical genius, able to tell stories that you know will agitate your audience into interruption and anger, and then to control and win over the crowds.

When we replant Jesus’s stories in their anthropological and ecological context, their radical anti-imperial vision becomes clear again. To tell a group of farmers that the kingdom is a like a mustard seed would have been an extremely divisive thing to assert. The mustard weed was pernicious in Galilee and could decimate a crop in days. To have your crop destroyed was a death sentence. Your family would starve. You could not pay your taxes. You might be imprisoned or killed. To say that this deeply unjust moment where the Romans have seized your land is the kingdom … and not only that, but this weed that threatens your very life is the kingdom, would have inspired screams of protest.

I wanted desperately to try to bring back to life the kind of physically intelligent and emotionally expansive man who could risk telling such terrifying stories to a group of people who were dealing with an extraordinary amount of trauma.

What has been the reaction to your book thus far by those who’ve read it?

I wept as I wrote the last two hundred pages of this book, through the crucifixion and into its aftermath. It’s deeply painful to imagine the ways the Roman Empire constricted a people, an ecosystem, and extinguished lives and nascent loves. I felt for my characters as if they were human beings, my beloved friends that I lived alongside for the years of reading and researching this book. My readers have shared that they have cried as they finished the book. They, too, have felt this loss. This makes me feel vindicated in the long, hard hours of writing scenes that felt almost too heartbreaking to approach. These forgotten women have been resurrected enough by my grasping words that they can inspire tears in others. It has been deeply moving to hear this.

What was your aim in writing this book, and what do you hope readers will take away from it?

My greatest sorrow is that a man devoted to the earth, to the outcasts, to healing and sharing good, gets coopted by the very empire that shortened his life and his spiritual potential. This sorrow is matched by my sorrow that a movement that initially seemed to welcome women and highlight their wisdom, becomes the very apparatus of their oppression. How can we re-root and re-wild Jesus and Mary Magdalene so that they can once again flower into that initial promise of egalitarian community and ecological storytelling?

Of all the sources you investigated, which would you consider the most revelatory or important for those who wish to research on their own?

While I benefited from many sources—in particular the primary documents, historical accounts, and targums of the time—I always suggest that people spend time with the Gospel of Thomas, a collection of Jesus sayings found in the Nag Hammadi texts recovered in Egypt in 1945. Many biblical scholars and historians agree that the collection of extra-canonical sayings may predate the canonical gospels of the New Testament and thus offer a less diluted vision of who Jesus might have been. In these sayings we glimpse a Jesus who is wilder and trickier than we have been traditionally led to believe.

Likewise, many of these early texts that were later deemed heretical offer alternative visions of Mary Magdalene and Jesus. Jesus kisses Mary Magdalene on the mouth in the Gospel of Phillip and Mary Magdalene steps into the role of teacher in the Gospel of Mary Magdalene. “The Gnostic Bible” compiled by Willis Barstone and Marvin Meyer is a great resource for these early texts. In researching and understanding the historical context of Second Temple Period Palestine, I always recommend the work of Jesus Seminar scholars Bruce Chilton and John Dominic Crossan.

Can we hope for another book, and if so, what will be its subject?

I am currently finishing a memoir about disability and ecology titled The Body is a Doorway: Healing Beyond Hope, Healing Beyond the Human for Running Press. It will come out in Spring, 2025. And I’ve begun work on my next novel: a science fiction queer ecological retelling of Tristan and Isolde.

Kristine Morris