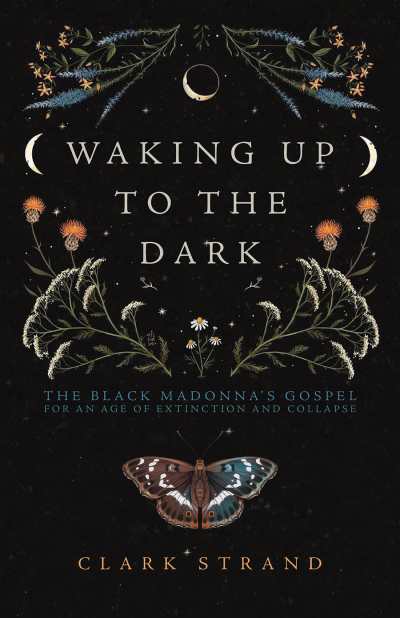

Reviewer Meg Nola Interviews Clark Strand, Author of Waking Up to the Dark: The Black Madonna’s Gospel for an Age of Extinction and Collapse

Based on the books we choose to feature in this weekly newsletter, you might guess that we’re quite open to alternative, out of the mainstream ideas about the natural and spiritual worlds, science and health. And it’s true, though perhaps the reason is because we see such an eclectic, fascinating array of books in our offices from North America’s independent publishing houses.

This week follows suit. Author, poet, former Buddhist monk Clark Strand is with us to talk about his extraordinary new book, Waking Up to the Dark, but be prepared: his final take-away is anything but cheerful.

Like others who recognize that we’re living at an ominous time in human history, Clark believes that “the rise of fossil fuels and petrochemicals, the discovery of electricity and the invention of artificial light” has taken such a toll on the planet that we “will not be able to avert the converging catastrophes of the 21st century.”

But all is not lost, he says, based on the wisdom of the ancients and—wait for it—the return of a Great Mother who will guide us through “a time when human ingenuity will be of limited force and effect.” The problem, in Clark’s mind, is that we have “fallen so far out of step with our evolutionary past that, when the [divine goddess] who guided our ancestors through ice ages, volcanic super-eruptions, and asteroid strikes finally reappears, we hardly know what to make of her.”

This Great Mother was known by many names: Isis, Ishtar, Kali, Gaia, and yes, in the West, the Virgin Mary—though the word “virgin” at that time referred to a woman who maintained her sexual independence—so, she’s familiar with us, and we with her, whether you know it or not. In the interview below, Clark offers another takeaway: “None of us are alone. If I had to sum up the message of the book in five words, that would be it.”

Meg Nola reviewed Waking Up to the Dark in the pages of Foreword and the following conversation is one for the ages.

On a side note, don’t forget that early bird pricing for entering the 2022 INDIES Book of the Year Awards ends September 30. Register today and click here for more information.

You’ve gone on “midnight rambles” or walks since you were a child. And these are lengthy excursions, not just a quick moonlit stroll around the block. Do you recall the first time you ventured into the night alone? Did you feel an unusual restlessness or something mystically luring you outside?

I began walking alone at night sometime during the summer of 1965, when I was around eight years old. It happened gradually. At first, I would wake at around 2 a.m. and lie quietly in bed until I fell asleep again. Later, when “waking up to the dark” had become a habit, I migrated to the back patio where I would lie in a deck chair for an hour listening to the tree frogs before heading back to bed.

The first time I set my hand on the doorknob to leave by the front door, I remember thinking that I was about to do something my parents wouldn’t approve of. But it felt natural once I’d done it a few times, and after that I never looked back.

I wandered the length of a nearby golf course at night through most of my Alabama childhood. We moved to northwest Atlanta in 1971, where I would cross the Chattahoochee River on a rickety one-lane bridge, following a road that dead-ended in a pitch-black forest two miles later. Atlanta was a smaller, darker city back then. This wouldn’t be possible today.

For college, I chose a small university in rural Tennessee. At that time, the University of the South had the largest campus in the world—ten thousand acres, most of it undeveloped. You could wander for hours at night without seeing a single electric light.

I was spiritually inclined from childhood on. But I wasn’t aware until much later how intimately darkness was connected to the soul. What drove me on those early midnight rambles wasn’t restlessness—spiritual or otherwise. What I felt mostly was the lure of beauty. To this day, nothing is more beautiful to me than the dark.

In Waking Up to the Dark, you describe the “daylight realm” of ambitions, goals, and actions. And then there’s night, which should be a time of dreams and replenishment, yet it’s often troubled by insomnia, worry, and even fear. During the night, what’s the difference between “The Hour of the Wolf” and “The Hour of God”?

An NIH study conducted by psychobiologist Thomas Wehr in the 1990s found that ordinary people, taken off artificial lighting for one month, all reverted to a primordial pattern of sleep. They would begin to grow quiet not long after sunset, turning in for the night about two hours later. After four hours of sleep, they would wake for two hours, following which they fell asleep again for another four. That discovery was impressive enough. But the biggest takeaway was what happened in the interval between those two periods of sleep.

Wehr’s subjects experienced a profound peace during that gap. But they weren’t exactly awake for it—or at least not as we ordinarily understand that word. The hormone prolactin, which keeps our bodies still while we are at rest, remained at sleep levels during those two hours. When I first read this, I couldn’t help but think of a line from the Song of Songs: “I sleep, but my heart is awake.” It was a state of consciousness not familiar to modern sleepers, Wehr concluded—one with an endocrinology all its own. The closest thing he could compare it to was the state reached by mystics in the depths of meditation.

This was the mode of sleep observed by Homo sapiens from the Paleolithic through the early modern age. It only changed with the dawn of the Industrial Revolution. Assisted by increasingly brighter forms of artificial illumination, eventually we compressed our sleep nights, like our workdays, into convenient eight-hour blocks. That was when The Hour of God became The Hour of the Wolf.

People still wake in the middle of the night, because it’s impossible to fully suppress that older pattern of sleep. But now they experience it as insomnia. Their prolactin levels fall soon after they wake, especially if they check their phones or turn on the lights, and soon they are restlessly tossing and turning. If they can’t get back to sleep after that, the Hour of the Wolf arrives, so-called because of the eerie, predatory fatalism that tends to come calling on modern people in the small hours of the night.

It’s the perfect metaphor, really. The wolf represents an older, wilder way of being that the modern world sought to eradicate. But that older way can’t be driven to extinction. It’s still there inside of us. Our way of life has changed radically with the invention of modern lighting. Our biology had remained the same.

There’s clearly a sleep crisis in America, particularly when our phones and laptops follow us into the bedroom, keeping us distracted or connected to the outside world. Cumulatively, disrupted sleep affects both physical health and emotional well-being—yet a medicated, drugged sleep is also unnatural. How should we be sleeping ideally?

Ideally, we should turn out the lights at dusk and let the darkness have its way with us throughout the full period of the night. That’s all it takes to revert to our natural sleep cycle. But the sad truth is, most of us can’t do that. Because of our jobs. Because of where we live. Or who we live with. Because, in a culture so fully saturated in artificial illumination, the lights are everywhere—and they are always on.

Even Thomas Wehr, who knew the health risks of our thousand-watt lifestyle, didn’t believe there was a solution to the problem at the cultural level. When asked if people had a right to know that keeping the lights on after dark leads to host of ills, including addiction, obesity, diabetes, heart disease, cancer, mental illness, and/or premature aging, he said, “Well, yes, they have a right to know. They should be told; but it won’t change anything. Nobody will ever turn out the lights.”

I believe that’s why so many people seek an alternative that I call “the cultivated dark.” Wehr thought so, too. At the end of his study, he concluded: “Perhaps what those who meditate today are seeking is a state that our ancestors would have considered their birthright, a nightly occurrence.”

That statement helped me to make sense of my own life. I began practicing Zen Buddhism in my late teens, eventually becoming a monk in a remote monastery where the only lights after dark were candles. I am now convinced that it was the darkness that led me to Zen.

I just cited cellphones, social media, and the internet as being major causes of diminished sleep, but you note how we really started to lose this battle when Edison invented the light bulb. Electricity created more electricity, and now we’re overwhelmed by our “light-drunk modern lives”?

That’s right. We have gone so far down the path of light-assisted wakefulness that we are now addicted to it. Few people realize how powerful a stimulant artificial lighting is.

In the late 1990s, two researchers who were studying the modern diabetes epidemic came to a startling conclusion—that the root cause of it wasn’t diet … but light. Taking a deep dive into human paleohistory, T.S. Wiley and Bent Formby discovered that human beings once consumed carbohydrates only in season, fattening up on plant sugars in late summer in preparation for the winter. Women would typically conceive at this time of year, when their bodies had put on enough fat to carry them through pregnancy. The biological trigger for this all-you-could-eat carbo-feast was more hours of light.

When humans began to develop artificial lighting, they effectively “tricked” their bodies into thinking it was summer—which meant it was time to eat and mate like there was no tomorrow. This wasn’t a problem as long as the only light was fire. With the development of oil, gas, and electrical lighting, it became critical.

We now live in a state of perpetual “hunger”—for food, for sex, and for stimulants of all kinds—because our bodies are convinced that it is August every day of the year and there is no way to convince them otherwise. That’s because our bodies are responding directly to light, the “master switch” for all hormone production.

When you write of the “Dark Revolt” and to “Let there be darkness,” you stress that this doesn’t involve blocking out the sun or diminishing the day. There’s just more of a “return to time as we once knew it,” by following the organic rhythm of sunrise and sunset. How can we become part of this dark revolution?

The best wisdom is always to start from where you are. Over the years I have noticed that few people can alter their lives with grand gestures meant to change everything at once. So it’s important to stay grounded in the life you have.

Joining a Zen monastery in my twenties was supposed to be like a one-click fix for me. I was certain that it would be a reset for every aspect of my life. But it didn’t work, and eventually I had to leave. It took another twenty years of wandering through other spiritual traditions to realize that the Dark Revolution was an inner revolution that doesn’t depend on institutions or initiations. It’s in here, not out there. We can only come to it on our own.

How do we effect that inner revolution? I’ve come to believe that, for most people, it is better to work it from both ends at once. Experience the literal darkness as much as you can—by turning out the lights a little earlier each night until you have become acclimated to the dark. But don’t forget to cultivate the darkness, too—through prayer or meditation, yoga or chanting. Basically, anything that loosens the hold of our light-driven culture on your soul.

For some this can be as simple as lying down in a dim room once or twice a day and doing nothing for twenty minutes. No planning. No problem solving. No getting or spending. No going over the events of the day in your head. No nothing.

Daydreaming is vastly underrated as a spiritual practice in modern society. Loafing is another forgotten art.

In the book, you recount apparitions of a young woman with a luminous, “moonlike” face and a mouth bound by electrical tape. Once the tape was removed, she spoke in a voice that could both “bring life” and kill. Who is she and what does she have to tell us?

The apparitions are the real subject of Waking Up to the Dark. The first two sections of the book were an attempt to prepare the reader for them by explaining the basis for such experiences in paleobiology. But, really, there is no way to prepare for them. We have fallen so far out of step with our evolutionary past that, when the Dark Mother who guided our ancestors through ice ages, volcanic super-eruptions, and asteroid strikes finally reappears, we hardly know what to make of her.

At the end of the book, I referred to her as Our Lady of Climate Change, but that only scratches the surface. In the course of human history, she has been known by many names. In the Mediterranean Basin, she was Asherah, Astarte, Ishtar, Inanna, and Isis. In India she was Parvati, Durga, and Kali. In Greece, Gaia, or “Earth.” Our Paleolithic ancestors thought of her as the Great Mother.

In the West, the Virgin Mary is all that remains of her today. Christianity made Mary the human mother of Jesus. But the first Christians would have understood her as much more than that. The word for “virgin” that is used in the gospels referred to a woman, usually a goddess, who maintained her sexual independence. The Greek title parthenos described a woman who refused to submit to male authority—human or divine.

The girl who appeared to me took the form of the Virgin Mary, but she made it clear from the start that she had no interest in the Catholic Church. Her message, which comes in the last three pages of Waking Up to the Dark, is addressed to all of humanity. It begins with the words “Say to the nations …” and its theme is the return of the Great Mother to guide human beings through “The Great Narrowing”—a time when human ingenuity will be of limited force and effect. When nations will fall and the waters will rise. When what food remains will be local and not enough. When people will continue to argue with one another about what is happening and why—until, finally, there is no more argument, because there is no more doubt.

The core message her “Gospel According to the Dark” is that we cannot think our way out of the endgame scenario that was set in motion with the rise of fossil fuels and petrochemicals, with the discovery of electricity and the invention of artificial light. We will not be able to avert the converging catastrophes of the 21st century. But the Earth can guide us through them. She can guide us.

I never expected to encounter the Black Madonna or hear her gospel “for an age of extinction and collapse.” When my journey began, I had no idea that this was where it was leading. I was just a kid who wasn’t afraid of the dark and, therefore, had no problem being alone in it. Now I realize that I was never was alone in it. And maybe that is why I was never afraid. None of us are alone. If I had to sum up the message of the book in five words, that would be it.

Meg Nola