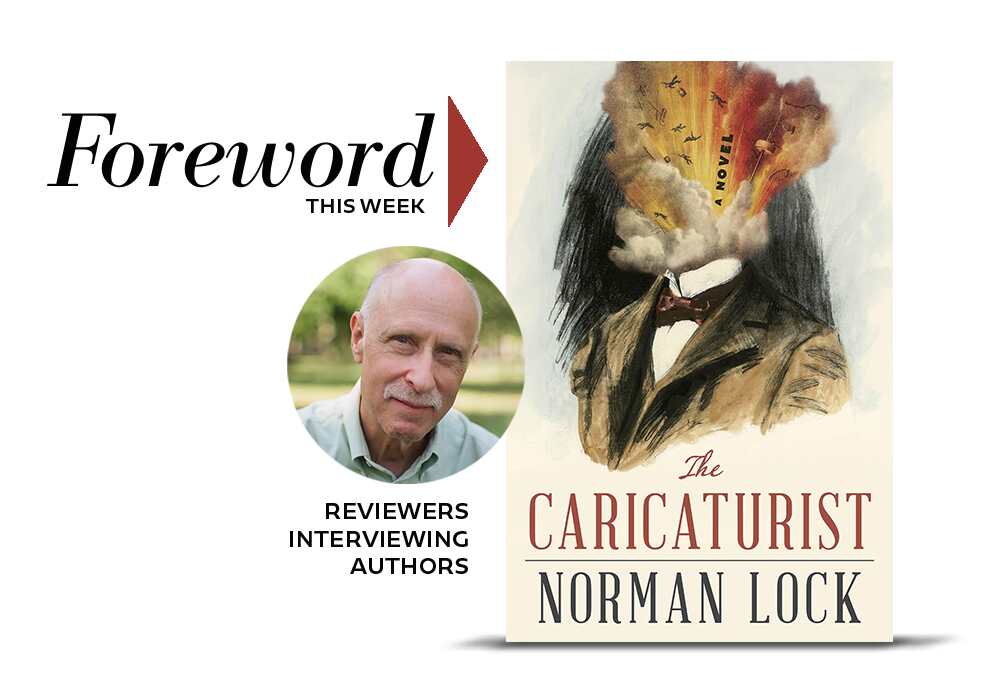

Reviewer Meg Nola Interviews Norman Lock, Author of The Caricaturist

“To write a story isolated in the past, without attachments to our own time (if such a thing is possible) does not interest me. I believe that a book is a responsible object brought into being by a writer, ie, it occupies a place among the manifold relationships of women and men within the web of life and is answerable to them.’’—Norman Lock

In today’s interview, Norman Lock offers refreshing candor about what authors do—and don’t do—when they write a book. Specifically, Norman points to literature of the past and states the obvious: that a “novel written today is influenced by novels from the past, whether or not the author is aware of the debt.”

Not that we’re trying to take anything away from the genius of all good writers, it’s just enlightening to understand what’s really going on when they do what they do.

In the ten-plus novels in The American Novel series, Norman has embraced his literary “indebtedness” to Thoreau, Melville, Hawthorne, Dickinson, and other greats of the past. That they have shaped our “literary consciousness” in the nineteenth century and now is something he delights in celebrating through his own works of literature.

Meg Nola wrote the starred review of The Caricaturist—number eleven in the twelve book series—in the July/August issue of Foreword Reviews and jumped at the chance to talk with Norman about literary debt and how history writes itself.

The Caricaturist and your other works in The American Novels series have wonderfully immersive historical backdrops, from the descriptions to the dialogue. How are you able to block out our very modern times while writing and channel these alternate timescapes?

The past is not a closed chapter. It exists within time’s moment-by-moment narration, whose numberless stories are always being written and whose truths are always in question. Like all other formulations of the past, history writes itself backward and forward, ie, it is written and rewritten constantly—an annotation of the changing historical consciousness, the opening and closing of the valves of attention, in Emily Dickinson’s phrase, activated by archaeology (in the field and library), enlightenment, or shame. Literary history’s own valves open and close as its awareness of itself enlarges and diminishes. Things will be left in or out of the account as society becomes more or less open. As one generation, school, or collective of writers yields to the next or competes contemporaneously for the reader’s attention, past writing’s forms, subject matter, and purposes may be ignored or studied, according to the urgencies of the day. Our past literature need not be used by contemporary writers only as décor or aids to nostalgia; it can be renovated in the interest of exploring present crises and persistent aspects of character; it can return from the grave of literary history to be an avant-garde. Tradition and innovation are locked in a dance of styles.

A novel written today is influenced by novels from the past, whether or not the author is aware of the debt. I declare my indebtedness rather than try to hide it. In The American Novels series, I take spaces in our national literature as my subject because I respect, even delight, in it and, more important, because I see incarnations of certain of its themes in today’s literary, social, political, and economic situation. The times may seem modern, but so much of what is thought of as having passed us by continues in the present.

To write a story isolated in the past, without attachments to our own time (if such a thing is possible) does not interest me. I believe that a book is a responsible object brought into being by a writer, ie, it occupies a place among the manifold relationships of women and men within the web of life and is answerable to them. Authors are under no obligation to please readers by confirming their beliefs. Instead, they must deal honestly with the conditions under which their contemporaries live, labor, suffer, and die. My ambition is to follow the threads that bind us, into the public space of events, which shapes the private one.

There’s intense protest activity in The Caricaturist, with various factions rallying both for and against the Spanish-American War. Even anti-imperialist Mark Twain joins the fray to sing: McKinley and American Sugar Co./Want a war, “a splendid little war!“/Not a big one, just a little one/Only ninety miles from our shore. Why was the country so polarized?

National unity is the expression (both slogan and product) of a dictatorship. Sectarian violence and, many times, civil war seem always to follow the overthrow of a dictator, when the lid is suddenly taken off the pressure cooker. Democracy, which in its perfect form respects dissent, engenders division. Puritans despised Pilgrims, as some Protestants do Catholics, and Gentiles Jews (and vice versa). One race is pitted against another; capitalists and workers are at each other’s throats; the interests of rich and poor are never reconciled. I am not a historian, but I suppose that what has thus far prevented class or religious wars in America is a tradition of law and toleration, however imperfect. Otherwise, we might find ourselves in the bloody free-for-all that followed the withdraw of the Communists from Yugoslavia, or the overthrow of Saddam Hussein, or—not to forget our own dismal example—the defeat of the American South and the Radical Republicans’ politically expedient end to Reconstruction, which left the fate of Black people to the KKK.

National unity is one of America’s grand illusions. In The Caricaturist, the complicated economic, political, and territorial issues of the day are shown to be subsumed under a general revulsion for the brutal Spanish occupation of Cuba, a cause célèbre the majority of Americans could understand in terms of the tradition of revolution and independence. Popular culture was mobilized to heat up patriotic sentiment and counter the dominant isolationist belief, using the social media of the day: songs, plays, poems, newspaper accounts of atrocities, mass rallies, and advertisements. Americans who would not have gone to war for the American Sugar Company or for the war hawks advocating an extension of America’s sphere of influence in the hemisphere were willing to kill Spaniards to liberate the Cuban and Filipino peoples. (The cause may have been just, but it was exploited for dishonest purposes. In our era, reiterations of this cynical practice occurred again in Cuba, in Guatemala, Vietnam, El Salvador, Nicaragua, Honduras, Iraq, Afghanistan, and elsewhere.)

Oliver was not fooled by easy appeals to his patriotism. He had socialist and anarchist friends. As a political cartoonist, he was part of the apparatus of consent. He was the renegade and outcast of a family strained to the breaking point by the disharmonies present, at large, in America. The current of his personal history, rather than the national delusion, carried him to Cuba.

It needs to be said that the anti-imperialists of 1897 were not uniformly motivated by the conviction that America should reject the profitable business of annexing Spanish colonies “vital to our interests,” as military or covert ventures would be described later in its imperial age. Many anti-imperialists, like Andrew Carnegie, were Nativists, the nationalists of our day, who believed in racial purity or, in the case of minorities like the German and Irish, feared competitors in the unskilled labor market. To his credit, Samuel Clemens (Mark Twain) opposed enterprises that were likely to get men and women killed.

Oliver encounters author and journalist Stephen Crane in Key West after war is declared, and Crane plays a pivotal role in Oliver’s experiences in Florida and Cuba—although the action of the novel ends on a boat steaming toward Guantánamo. Oliver also meets a Cavalry soldier named George P. Garnet in Key West. Can you tell us a bit about George?

Behind the fictional character George P. Garnet is a man who suffered under conditions that were nearly universal for Black people after the failed Reconstruction of the Confederacy and the entrenchment of racial injustice and its codification in law, in the North, as well as the South. There are many like him in The American Novels series, and as for any character in a story or play, they are there to make apparent a theme or enlarge a reader’s understanding of the author’s intention—in other words, to serve the author’s purpose. I chose George Garnet because he was a Black man whose army uniform did not protect him from race hatred; moreover, he was a Black man exploited for a supposed immunity to malaria, yellow fever, and other tropical diseases.

Whether a character is copied from an actual person or assembled from aspects of several people (no character is entirely an invention), writers may be made uneasy by their exploitation. (Expropriation is a major theme in The Caricaturist.) Since writers cannot truly know others, the dimensions of their sorrow and pain, they will be liable to criticism. To use someone, even an imagined someone, as an illustration is offensive. I plead sincerity, goodwill, and an outsider’s obligation to use art to understand another’s life and, by doing so, help that life to become more bearable. I am not advocating a didactic or moralistic literature, but rather one that asks readers to consider ethical responsibility, among other issues posed by the novel.

To claim for one’s work a moral purpose makes most engaged in making and discoursing about it nervous. Morality is not an absolute, and those who pretend otherwise can become self-appointed censors. But simply showing immoral behavior on the page may not be enough if the reader can no longer see it for what it is.

Standing beside George Garnet, looking across the night-blackened Florida Straits toward Cuba, Oliver cannot plainly see the Black man’s face. Later, in his hotel room, Oliver fails in his attempt to sketch him and burns the drawing. These actions point to the darkness in which each of us struggles to make a human connection with someone else.

Franklin Barrett is Oliver’s grandfather in The Caricaturist, and you note in the afterword section that he was based on your own great-grandfather. He grows orchids and keeps a pair of live alligators in a “cement swimming pool;” he also has his own artistic inclinations and is an admirer of Oliver’s unofficial mentor, the realist painter, photographer, and sculptor Thomas Eakins. What sort of family information did you have to work with to include Franklin in the novel?

I was born into history in 1950 and into a continuum that began, for me, in the late nineteenth century. In other words, I became conscious of the past as I became aware of the world of the present. I grew up a mile from the house where my mother was born, the same house to which her father’s parents had moved (along with his brother and sister) from a German section of downtown Philadelphia to the rural, unincorporated area of the city, which Olney was in 1910. That is the house at 5531 N. Third Street, which Oliver turns his back on and where his sister, my great-aunt Dot, remained, unmarried, for the rest of her days.

My mother’s mother, Helen Barrett, was born in 1899 and raised in the house described in The Caricaturist, where her father, Franklin, tended tropical flowers, Japanese fantails, and, yes, a pair of alligators, on the estate of Philadelphia meatpacker Henry Burk, in the last decade of the nineteenth century and the first one of the twentieth.

My mother’s family is well documented; they kept every receipt, from the payment of the poorhouse tax to bills for coal delivery, every beautifully handwritten deed and document, every card and letter, Daguerreotype and photograph. Oliver’s father, Charles, was as he is presented in the novel: a pigeon fancier, a Lutheran, a bigot, and a banker. His strict, Germanic character asserted itself over every aspect of the household, from his wife and three children to the ledgers in which he recorded every purchase, in his neat, clerical hand, down to a loaf of bread or ball of twine.

In my boyhood and well beyond it, I rummaged through that wealth of family history. In that house, I absorbed not only the facts of my lineage but those of a particular America, one that existed for a kind and class of people many years before my birth. (I am far less aware of my father’s Jewish origins in Latvia, Lithuania, and Poland, which were lost in the twentieth-century diaspora and his own Depression-era displacements and to his unwillingness to speak of certain cruelties.)

The Caricaturist is the penultimate book in The American Novels series, and you’re presently working on the final novel. Does the writing of this last book differ from the others, in terms of your emotional connection and feelings of completion?

The final book, Eden’s Clock, is finished. The wish to write a novel with Jack London present surprised me, occasioned by my reading in one of his biographies that he had borne witness, with his words and Kodak, to the immediate aftermath of the 1906 San Francisco earthquake and fire. Moreover, Enrico Caruso had performed, just hours before the first tremor, at the city’s opera house. Such a confluence was too fortunate (the occasion being far from it) to ignore.

Do I feel a sense of completion? Not entirely, although there is satisfaction in finishing what I began ten years ago, after the idea of a series became apparent. For reasons having to do with relevance as much as remembrance, I would commemorate nineteenth-century American writers whose works shaped our literary consciousness more powerfully than those of their contemporaries (and continue to influence it): Poe, Emerson, Thoreau, Melville, Hawthorne, Whitman, Emily Dickinson, and Stephen Crane. (Henry James appears briefly in American Follies, but I chose to consider his novels a twentieth-century contribution to our literature.)

Jack London and the San Francisco earthquake signal, to my mind, the end of the age of American optimism and the start of something dangerous and terrible. Many of his stories and novels prefigured Hemingway’s, just as London’s socialism does the 1930s naturalism begun by Stephen Crane and Hamlin Garland. And it seems fitting to me to conclude the series with that most powerful influence on the American character—western expansion and the dream of Whitman, as they came to a vividly symbolic end on April 18, 1906, in the upheaval and burning of the great American city on the Pacific, itself once a Spanish possession.

Meg Nola