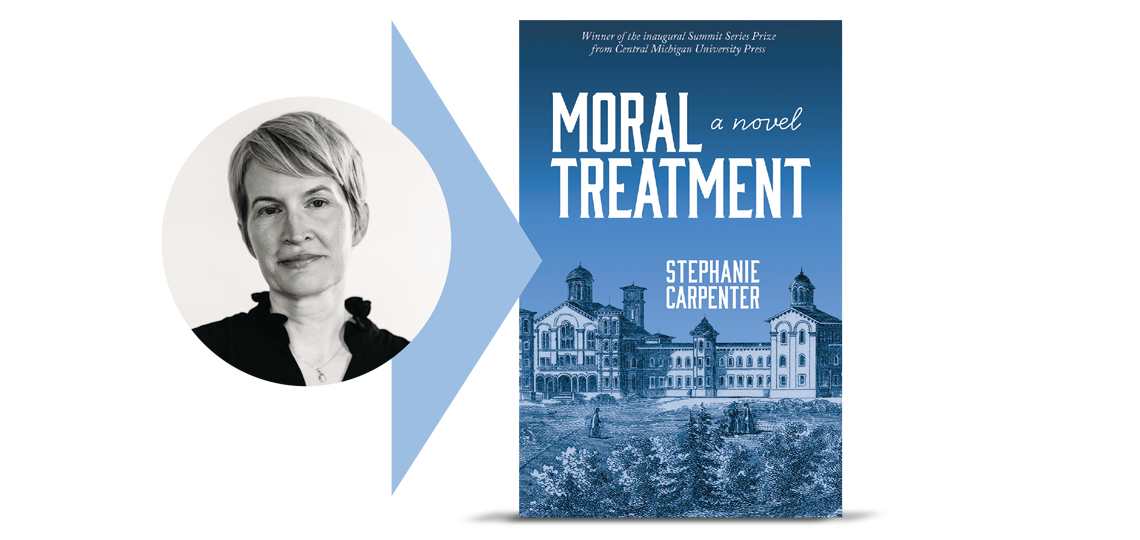

Reviewer Meg Nola Interviews Stephanie Carpenter, Author of Moral Treatment

You note in your acknowledgment section that the institution in Moral Treatment is based on the Northern Michigan Asylum, which opened in 1885. You also had family members employed in various capacities at the Traverse City State Hospital. Were you intrigued by the general history and environment of the Traverse City facility while you were growing up?

“Based on” is crucial: the people and situations in the novel are entirely invented! But the hospital is quite closely modeled after the Northern Michigan Asylum, which in my day was called the Traverse City State Hospital. The last of the State Hospital’s facilities closed in 1989; redevelopment of the vacated buildings didn’t begin until the early 2000s—meaning that during my teenage years, the place was abandoned, eerie, and irresistible. I know a lot of people who managed to get past the security guards and inside the buildings and underground tunnels. (I never did).

How did the moral treatment method differ from previous approaches in managing mental disorders?

The moral treatment emerged in Europe in the mid-eighteenth century; it became popular in the US in the early- to mid-nineteenth century. The principles might seem like common sense: mental illness should be regarded as a medical disorder and treated systematically and humanely. Patients should be fed well, kept safe, treated for any accompanying physical diseases and ailments, provided with occupational therapies and entertainments, given access to fresh air, given regular baths, etc. Basic drug treatments were used, as well.

Before this, mental disorders were understood as forms of social deviance, or even as evidence of demonic possession. Treatments were punitive: people were restrained, beaten, subjected to harsh purgatives, and sometimes put on display to the general public—most famously, at Bethlem Royal Hospital in London, or “Bedlam.”

The eugenic practice of sterilizing individuals with mental illness is a recurring dilemma in the novel. As one of the younger physicians insists: Should medicine sit by while such people propagate and marry? You wouldn’t breed one of your cows, would you, if she were defective? Conversely, the hospital’s superintendent physician, James, views sterilization as an abhorrent, “god-like ideology.” Was this a legitimate medical movement at the time, to essentially improve the “breeding stock” of humans?

The eugenics movement emerged in the 1880s and some asylum doctors adhered to its ideas. Their interventions were not producing “cures,” and with more people arriving than leaving, psychiatric hospitals across the US were growing in size and increasing in number. Practitioners understood that mental illnesses were often hereditary, and some felt that preventing people with mental illness from having children was the only certain way to slow the spread of these disorders. (In the scene you’ve quoted, my characters are actually discussing people with intellectual disabilities, who were expressly prohibited from being admitted to Michigan’s psychiatric hospitals.)

I’d seen eugenic arguments in The American Journal of Insanity, a trade publication for asylum superintendents. I was surprised to see signs of that ideology in some of the annual reports from the Traverse City hospital, and when I did, those ideas entered the novel. My fictional superintendent is flawed in many ways, but he’s horrified by the premises of eugenics. The younger doctors see his attitude as old-fashioned.

Are you working on any new fiction projects?

My completed collection, Many and Wide Separations: Two Novellas, is under representation and will hopefully go out on submission in the spring. The novellas tell the stories of two women artists in nineteenth-century New England, fighting to find their voices in spite of family members and lovers who feel entitled to speak for them. I’m currently working on a handful of short stories and on a longer project, an eco-gothic, post-apocalyptic novella that imagines what kind of nature gods might emerge from a landscape devastated by climate change. It’s written in a slanting rhyme and meter, which is new for me.

Meg Nola