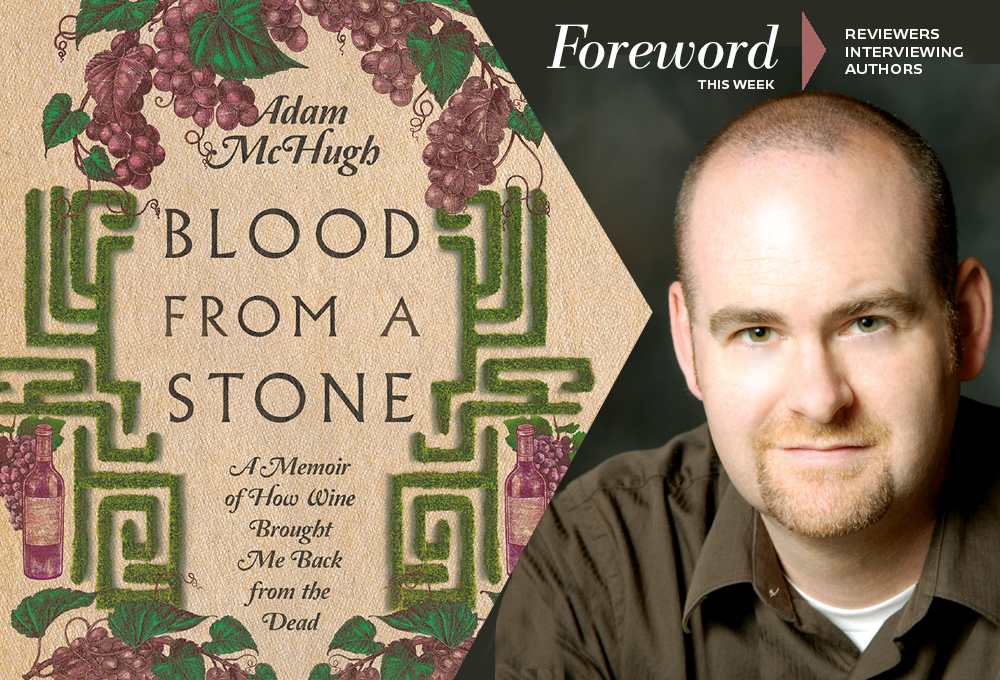

Reviewer Melissa Wuske Interviews Adam S. McHugh, Author of Blood from a Stone

When God calls to offer you a job, you’re not likely to let it go to voicemail. And if you become a minister or rabbi or nun and spend years doing the good work, the idea of quitting would certainly make for a tough decision. It’s not the same as leaving McDonalds for Taco Bell.

Adam McHugh was a man of God who walked away to become a man of wine—but he knows God is happy for him. Here’s how he describes the change in employment from hospital chaplain to grape farming: “I thought my life’s calling was to focus on ideas perched in the high places far above the ground. I was wrong. And the path to healing for me has involved getting my hands dirty.”

Melissa Wuske recently caught up with Adam for this week’s interview after reading and reviewing his newly released Blood from a Stone memoir for Foreword’s November/December issue. Enjoy!

The book is rich with metaphor—including the ripening and fermenting of fruit and the importance of soil for growth. How did the richness of ideas like these draw you toward wine and healing?

It was intimidating to write a book about wine and wine country, because of just how much knee-bending beauty and inspiration is inherent in the world of wine and in the places where vines grow, and I was afraid my words couldn’t measure up to their glory. And they probably don’t, but I tried for four years to find some adequate words. For me, what was most compelling about the people who farm and ferment grapes is how grounded they were, in every sense of that word. I had been living a life that felt unsettled and placeless, never staying too long or going too deep with the same people. I thought my life’s calling was to focus on ideas perched in the high places far above the ground. I was wrong. And the path to healing for me has involved getting my hands dirty.

Faith is a central element of your story. How would you describe how your faith, or your understanding of faith, changed over the course of the story in your book?

When you are a pastor and a hospice chaplain, you wear religion on your sleeve in just about every situation. Sometimes it can be an inviting presence, especially if the person you are talking to has a positive religious background, but often it was awkward, even off-putting, for people. It’s just an intense way to introduce yourself to someone you have never met. It feels like it kills all potential for small talk or a more natural and gradual entry into a relationship. It’s like you are leading with the deepest thought you have ever had. I never reveled in playing the role of a religious authority figure. It never felt like a great fit for me, though I am deeply grateful for how I was changed through that work.

Some people wondered if I was giving up the faith by leaving ministry. It’s just now my faith is a more personal and private experience for me. I still believe the universe bleeds over with love, as hard as it can be to see sometimes. But I talk about it much less, and I am content to hold far more questions than answers. And I relate to people more comfortably and casually, which has been a relief. I don’t kill small talk anymore by simply telling people what I do for a living. Now when I tell people what I do for a living, their eyes light up. There is a joy and conviviality in sharing a bottle of wine that gives many people meaning and belonging.

Many memoirs, like yours, are focused on the internal life, but your story also showcases the importance of people and place in a person’s life. Why do you think those elements are so critical?

I talk about this extensively in the book, that finding your place is not only about discovering a particular location on earth that feels right, but finding a sense of belonging among the people that share that location. In the world of wine, place is an exalted concept. Many of the best wines are said to express a “sense of place,” meaning that a great wine carries something distinctive and unique that distinguishes it from a wine originating in any other place. Many winemakers talk about wine being “grown” rather than “made,” and they feel their role is to get out of the way as much as possible and let the wine, and its place, speak for itself. But their role is absolutely critical. Place is both location and community, gift and labor, and together nature and humans work to create something meaningful and beautiful—a place that feels like home. My story is one of coming home.

Your story begins with ministry burnout. What advice do you have for ministry professionals or others in caring professions who are burnt out or want to prevent burn out?

If I knew the answer to that question, I might not be working full-time in the wine industry! Burnout was one of the best things that ever happened to me. I suffered not only from the emotional weight of my chaplaincy work, called compassion fatigue, but from the feeling of being displaced in my work and life. I was low on energy because I wasn’t in the right life. For me, the answer to chronic burnout was to find a better place.

You’ve written several other nonfiction books (Introverts in the Church, The Listening Life). What was different or challenging about this one since it focuses on your personal story?

This one was far more fun. I love not having to write as a minister anymore, where you feel like you need to run your language through a religious filter, even if you don’t talk like that in daily life. I let my full personality out of the bag on this one, which no doubt will scandalize a few religious people if they read it. I got to be sarcastic and whimsical and ridiculous in this book and drop in a bunch of asides and pop culture references. It feels very authentic to my voice, and it gave me energy rather than taking it away.

I enjoyed writing a very personal story, as long as it was just me and my laptop and my cats and I could play around with it. When I write the first draft I try not to think about how readers will receive it, because that can be paralyzing. But then I had a moment this fall when I realized people are actually going to read this book. Now it feels very vulnerable. Hopefully that means I wrote something true, and human, and it will resonate on a deep level. I will just be hiding under the bed for a while if you are looking for me.

Describe the experience of the best glass of wine you’ve ever had: where were you, when was it, who was with you, and, of course, what was the wine?

I devote almost an entire chapter in the book to this occasion, so I won’t give away too much here. I was sitting in an open courtyard in the south of France, in the shadow of a looming Gothic castle, eating like a five pound Salad Niçoise, and the wine was a carafe of house rosé. It cost eight euro, was probably made by the owner of the restaurant from his backyard family vineyard, and it was pure revelation.

What are your favorite books about wine or related to wine?

The Wine Bible, by Karen MacNeil, is not only my favorite book about wine but one of my favorite books of all time. A lot of wine books read like textbooks: full of great information but dry as an old cork. But Karen writes with a flourish, and her book is entertaining and witty, as well as being a reservoir of deep knowledge. I don’t know how she kept that up for 700 pages, but she did.

What tips do you have for novice wine lovers trying to learn and deepen their enjoyment?

Drink broadly, be open, and pay attention to what you taste rather than just letting its effects wash over you. Notice the color, the viscosity, the clarity, the aromas, the flavors, the length of the finish. Get all your senses involved. It is a fun and joyful process.

Instead of looking at grocery store shelves, find a local wine shop with a passionate expert and ask questions. You don’t have to spend a lot of money to find good and interesting wine.

Melissa Wuske