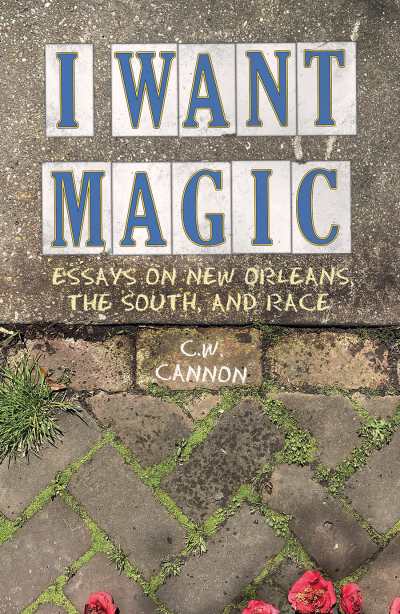

Reviewer Michele Sharpe Interviews C. W. Cannon, Author of I Want Magic: Essays on New Orleans, the South, and Race

If there is any doubt about God having a sense of humor, the old joke goes, you need only look at his decision to combine the human sex organs with the sewage disposal system. Questionable design, to be sure.

Likewise, America’s city planners must still be grinning about the placement of its most liberal, hedonistic city smack dab in the country’s most culturally conservative region.

New Orleans fits in the Deep South about like Ozzy Osbourne being adopted into the Osmond family.

This week, we’re joined by C.W. Cannon, author of a fantastic new collection of essays entitled I Want Magic: Essays on New Orleans, the South, and Race. In the interview with reviewer Michele Sharpe below, C.W. talks about New Orleans’ ironic location deep in the land of Dixie, but notes that The Big Easy represents another south, a “south that does not stake its identity on conservative politics. Southern right-wingers have always tried to equate southern identity with their reprehensible racist, misogynous, homophobic, and nativist politics. New Orleans has long been a magnet for southerners who reject that political equation.”

So, drape some beads around your neck and, hell yeah, pour yourself a Sazerac Cocktail, and let C.W. do a little NOLA nostalgializing.

Several essays in your book showcase New Orleans’ unapologetic sensuality. What sort of wisdom can the city offer to those who want to reclaim their exuberance after living through the COVID-19 pandemic?

Yes, one of New Orleans’ contributions to the larger American debate over life priorities is the emphasis on the value of sensual fulfillment. Sensual experience can range from enjoying fine food, to dancing in the street, to self-medicating in various ways (to enhance the sensual dimension), to unapologetic sexuality. I’m far from the first to recognize New Orleans’ embrace of sensuality as a salutary counterpoint to Anglo-American puritanical repression. As Henry Miller put it after a visit to New Orleans in the 1960s, “here at last on this bleak continent the sensual pleasures assume the importance they deserve.”

COVID-19 put a damper on public gatherings, but did not hamper people’s ability to enjoy home-cooked meals and celebrate one another in smaller, more intimate settings. One dimension of sensual experience is covered through the sense of sight, however, and the appreciation of visual (or aural) beauty does not bear any kind of risk of infection. Reminding ourselves to appreciate beauty on a daily basis is great therapy for coping with the hypocritical world of ideology, which has a way of operating beyond or in spite of sensual perception. I’m happy to report that New Orleans is now relishing the cessation of the temporary cramp in our lifestyle caused by necessary emergency measures. I’m pleased that New Orleans was among the first cities in the country to institute proof of vaccine to visit bars, restaurants, and other places of public accommodation, because it allowed us to resume our culture of public drinking and dining with the knowledge that we weren’t endangering the lives of our neighbors. This vaccine requirement also helped enable a high vaccination rate locally (sadly not statewide), which is another reason we were able to get back to partying without running the risk of harming others.

An old slogan—not sure where it came from, but it may have been a previous mayor’s office—is that “New Orleans knows how to party.” Knowing how to party means doing so responsibly. Other municipalities have tried and failed to stage Mardi Gras-level public celebrations, and to legalize alcohol consumption in the public space, a right New Orleanians have always enjoyed. An established culture of partying essentially tracks with the harm reduction model of dealing with addiction. New Orleans has long recognized that sensual impulses are not only irrepressible, but also natural and healthy to gratify. That understanding about the sensual dimension of our lives brings sensuality into the light of day and allows for reasonable community discussions about balancing the will to party with other concerns. Shamelessness, in other words, amounts to productive civil discourse.

I was intrigued with your observation that in New Orleans, white people can “celebrate their southern cultural identity without the millstone of hate that southern conservatives attach to it.” Can you expand on this observation with an example or two?

What I was referring to there was the way in which New Orleans has long served as a haven for southerners who deplore the social conservative politics of much of the region but who nevertheless feel themselves as southerners culturally. This applies in different ways to Black and white southerners, but I, being white, talk more about how white people view their region and city (leaving Black authors to cover Black feelings on those issues).

The most visible example of southerners who speak, eat, dress, and feel in southern ways, but who loathe southern conservatism, are LGBTQ people. The neighborhood I grew up in was largely defined by gay and lesbian neighbors with southern accents. Jews are another example. The Jewish populations of many small towns in the southern Mississippi Valley have dwindled to near nothing as southern Jews have migrated to urban areas where they feel more comfortable. New Orleans is home to the Museum of the Southern Jewish Experience, and to the oldest synagogue west of the eastern seaboard. The seersucker suit, now seen as a quintessentially southern fashion statement, was invented by a Jewish tailor in New Orleans—Joseph Haspel—in the early 20th century. Jewish New Orleans is one example of a uniquely southern social formation that doesn’t get much attention in the typically reductive stereotype of the south as rural, protestant, and conservative.

Broadly, the emphasis on culture in New Orleans seeks to celebrate aspects of the south that don’t have the divisive ramifications of the south’s repulsive political history. New Orleans is home to the Southern Food and Beverage Museum. The city is also, of course, a mecca for musicians and musical styles from across the region (not just jazz). Emphasizing music and cuisine as profound achievements of southern folk culture is a way to celebrate being southern without the political baggage, especially considering that the creators of southern music and food (and literature) have often been a part of what Carl Degler called “the other south,” the south that does not stake its identity on conservative politics. Southern right-wingers have always tried to equate southern identity with their reprehensible racist, misogynous, homophobic, and nativist politics. New Orleans has long been a magnet for southerners who reject that political equation. Our removal of white supremacist monuments in 2017, which caused a howl outside the city, was a great sign of the kind of south New Orleans seeks to represent.

How can New Orleans make its housing and culture available across class boundaries despite the intense gentrification pressures you detail in your essay “Adieux, Vieux Caré”? Or is New Orleans doomed to the fate of the French Quarter, what you called “the transformation of the city’s oldest neighborhood into a retirement community for the rich and boring”?

I will have to admit to a degree of native fatalism as I respond to this question. I don’t really see many ways to counteract the displacement of longtime New Orleanians by people from other places with more money. I sometimes get annoyed at the term “gentrification” itself, because it seems to obscure more than it illuminates. What we call “gentrification” is just capitalism. People with money get to do whatever they want and those of us who are short on cash just have to pick up and move if they say go. The suburbanization of an earlier era is what enabled affordable urban cores, and now the money wants back in and I’m not sure there’s anything that can be done in a country that is so reluctant to infringe on the prerogatives of capital.

One thing I’m absolutely sure of is that there’s not much that can be done by city government. The people of New Orleans have taken measures to improve economic prospects for neighbors of limited means, but the state or feds have come in to stop it. I voted along with a large majority of New Orleanians back in 2002 to raise the minimum wage in the city above the federal minimum. But the state legislature—a bunch of guys not from New Orleans—passed a law nullifying that popular mandate. Our city council passed a strict short term rental regulation in 2019, supported by the vast majority of New Orleanians. It limited short term rental listings to people who get a homestead exemption, which demonstrated that they lived at the property and were renting out one side, for example, of a double shotgun (duplex). Just yesterday, a conservative, Republican-appointed panel of the 5th Circuit Court of Appeals ruled that the law discriminates against out-of-state property owners. New Orleanians don’t like the prospect of the city getting bought up and rented to tourists by property developers who don’t even live here, but the overarching bias toward capital in our national economic system doesn’t care if New Orleanians can still afford to live here or not. In short, New Orleans voters are no match for more politically and economically powerful forces who don’t live here.

What are your views about the role of journalism in creating change at the community level?

I think local journalism has a great way of reaching the minority of people who engage with it. The local website, The Lens, printed many of my essays and, more importantly, has put forth incisive investigations of political, social, and economic matters affecting the lives of city residents. But I think we’ve arrived at a place in American social history where the maximum of people that intelligent journalism can reach has already been reached. Thank the gods for the committed local journalism at The Lens, The Times-Picayune,* Louisiana Weekly*, Big Easy Magazine, Antigravity Magazine, and a couple of our local TV news networks.

I’m proud that New Orleans has such a healthy stock of serious journalism and consumers of it. But as I said before, a critical mass of Americans are beyond the reach of serious journalism and, though they mostly don’t live in New Orleans, their misinformation ecosystem (Fox News, etc.) trains them to think in the kinds of platitudes that defy not only reason but any kind of local nuances or contingencies as well. It’s often reported that more and more local elections are being decided on hot-button cultural distractions at the national level. While New Orleanians are mostly not under the spell of these culture war spectacles, I’m afraid most of the state of Louisiana is. And that limits what we can feasibly accomplish on our own.

Do you have any plans for a current or next book project, and if so can you reveal them?

I’ve got two writing projects going now, which is to say I’ve started both but haven’t finished either. One is a memoir of my childhood and youth in the downriver neighborhoods of New Orleans (French Quarter, Marigny, Ninth Ward). These neighborhoods were more racially mixed then—1970s—than they are now, and more diverse also in terms of age, family status, lifestyle, and gender identity. It was a fascinating time and place to grow up, though also somewhat dangerous, violent (which makes for fun reading). My other project is a series of essays about iconic works of New Orleans literature, a subject I’ve taught for twenty years at local universities. The essays are more personal than academic, but do seek to unpack and analyze how three centuries of writing about New Orleans have shaped the imagination of successive generations. I’ve already got chapters on Alfred Mercier, Kate Chopin, John Kennedy Toole, and Brenda Marie Osbey.

Michele Sharpe