Reviewer Michele Sharpe Interviews Catherine Coleman Flowers, Author of Holy Ground

“I’ve been doing this work for a long time, and I’ve found that my deep commitment to justice and the well-being of affected communities is what keeps me going. It’s about finding strength in solidarity and small victories and having faith that in the long run, justice will prevail.’’ —Catherine Coleman Flowers

There’s good being done in this country, let’s not forget it. Catherine Coleman Flowers, for example, has devoted her life to environmental justice causes in the US, including decades of work in rural Alabama improving wastewater and sewage treatment. Not the sexiest of issues, but sanitation is a lifesaver—hookworm and other intestinal parasitic infections can do devastating damage—and her research shed further light on the links between racism, poverty, and environmental injustice.

A MacArthur Genius Grant plaque hangs on her office wall for all those good deeds.

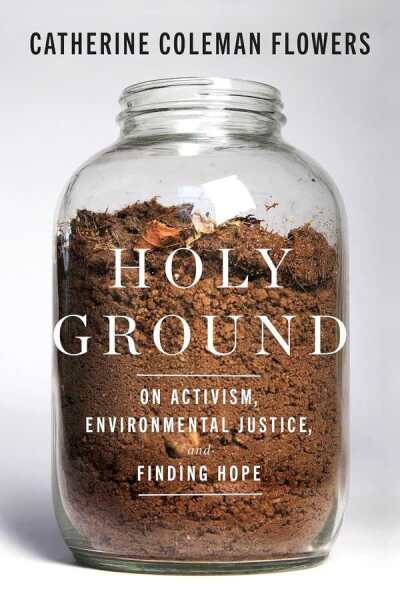

Back in 2021, we reviewed Catherine’s first book, Waste: One Woman’s Fight Against America’s Dirty Secret, in the pages of Foreword. Her latest, Holy Ground, earned a sparkling review from Michele Sharpe in the January/February 2025 issue. The following conversation will keep you inspired well into February.

You can find reviews of five more environmental books in the Climate Change feature (PDF here) in Jan/Feb. And then, why not take a minute to register for a free digital subscription to Foreword?

When I began reading Holy Ground, I was unaware of the extent of poor sanitation in the United States. Holy Ground taught me about the reality as well as the history and policies that permit it to this day. For me, the way you embed your personal observations into scientific material was effective as a teaching strategy. How important is it for you and other activists to connect the science with real life experiences, especially as you communicate with lay audiences? What sort of feedback have you received from audiences who were unfamiliar with the problem of poor sanitation?

Connecting science with real-life experiences is crucial because it helps translate these seemingly abstract concepts into tangible realities that resonate with people. Personal stories make the issues more relatable and urgent and give a face to the issue. I’ve taken several policymakers and other changemakers to see how sanitation inequality affects real people first-hand, and they have all told me that seeing it in person opened their eyes to the harsh realities of problem, particularly among those previously unaware of its extent in the US. That’s how we get people to care and drive substantial change.

The book’s rhetorical choices sometimes seem geared to specific groups of people. For example, the first essay makes brilliant use of “thirty pieces of silver” as a metaphor. That metaphor will resonate with readers who are familiar with the New Testament, but it might miss the mark with folks from other religious traditions. How do you make decisions about including cultural references in your essays and speeches?

It’s important to me to share from my heart and experiences in my work, so I try to lean into the metaphors that feel meaningful to me or show who I am as a person. But when using a specific reference, I aim to ensure its broader relevance or provide context to bridge any gaps in understanding. It’s a balancing act between staying true to the message and making it accessible to all.

Speaking of cultural references, I was reminded of Faulkner’s assertion that “the past is never dead. It’s not even past,” when reading your summary of the history of Alabama’s Black Belt. Toward the end of the book, you note that as a teacher, you believed “the greatest gift that I could give my students was the power of historical knowledge.” Holy Ground makes an air-tight argument about how the history of racism and class bias in America have enabled public policies that support water and sewer infrastructure in white and middle-class neighborhoods, while leaving working class and Black neighborhoods to often manage these essentials without government support. Is an understanding of history something that’s relevant to all your work? How can we help future generations access and value knowledge of the past?

Incorporating historical knowledge is integral to my work because it lays the foundation for understanding current injustices. By teaching the past, we empower future generations to recognize patterns of inequality and advocate for change. History, of course, needs to be part of our education system, but we also need our leaders incorporating it as they advocate for social change. We also need to give a voice to communities to tell their stories—from past and present—widely among public discourse. It’s an essential tool for building informed, active citizens.

Given that the entire country is at risk for the combined effects of sea level rise and excessive rainfall, is there a timeline you envision for eliminating septic systems and connecting all residences to public sewers? What would be some first steps toward achieving that goal?

It’s an ambitious goal that requires a phased approach and a lot of public buy-in. A realistic timeline depends on political will, funding, and public awareness, but starting now is imperative. Some of the first steps would be documenting the problem. It looks different depending on the location. There is a need for a national database on wastewater infrastructure in rural as well as urban communities. We need to prioritize the communities that do not have it by providing funding and support. In addition, we need to work on new technological innovations that incorporate the knowledge of local residents experiencing the issues first-hand.

In the essay “Migrations,” your search for ancestors using DNA genealogy becomes powerful evidence of how human beings are connected with each other across the globe. Have you had any success in countering racist arguments or policies using similar DNA and genealogical data?

My research of my ancestors and discovery of connections with family members that I did not know does challenge the concepts about race, especially those family members’ personal concepts about who they are. In addition, I think it helps provide a perspective they may not have considered if they too did not share African DNA or have a relative of African descent. On a wider scale, I will continue to use my own history to challenge outdated policies and concepts about race. And yes, I believe I am producing minor victories.

Holy Ground documents your success as a political advocate who has negotiated with elected representatives from both sides of the aisle. At present, our country is having great difficulty overcoming the limitations of partisan politics. What would you tell young people today about interacting with others whose party affiliations are different than their own?

I always say I’m most inspired by young people in my work—they motivate me and keep me moving forward. Because they’ve grown up with the various echo chambers on social media, I emphasize to them the importance of interacting with people of differing views in an open and understanding way. It’s about finding common ground and building relationships that transcend partisan divides. Approaching others with empathy and a willingness to listen is key to fostering constructive conversations and collaborations.

Despite the book’s emphasis on history, your concerns are very much in the present. This was most evident to me in “Disinvestment,” which describes the overwhelmingly white, Republican, Mississippi state government’s shameful abandonment of Jackson, the capital city, which is predominantly Black and politically progressive. You note that access to drinkable water—or at times, to any water at all—is unpredictable because the city’s infrastructure has slowly disintegrated over decades in what you call “a slow-motion assault.” It’s a maddening, frustrating situation, in addition to being a health risk for citizens of, and visitors to, the capital. How do people like yourself, who are committed to the good of all, manage to keep going in the face of this sort of pernicious, slow-motion assault by powerful opponents? And can you give us an update on the situation in Jackson?

I’ve been doing this work for a long time, and I’ve found that my deep commitment to justice and the well-being of affected communities is what keeps me going. It’s about finding strength in solidarity and small victories and having faith that in the long run, justice will prevail. Regarding Jackson, while there have been some efforts to address the water crisis, much work remains, and we must continue to advocate for the necessary resources and support for sustainable solutions.

Michele Sharpe