Reviewer Michelle Anne Schingler Goes Retro with Sarah Archer, Author of The Midcentury Kitchen: America’s Favorite Room, from Workspace to Dreamscape, 1940s–1970s

In the late 1800s, the wonders of electricity transformed the American landscape—streetlights, streetcars, engines in factories—in perhaps human history’s greatest game-changing technology. And in the following handful of decades, shit got real inside the American home with electrified appliances like refrigerators, hot water heaters, cooking ranges, washing machines, and vacuum cleaners. Looking back, it’s difficult to comprehend how these inventions changed housekeeping, changed the lives of women. Remember, until modern appliances appeared, cooking at home was still much as it was in the Middle Ages.

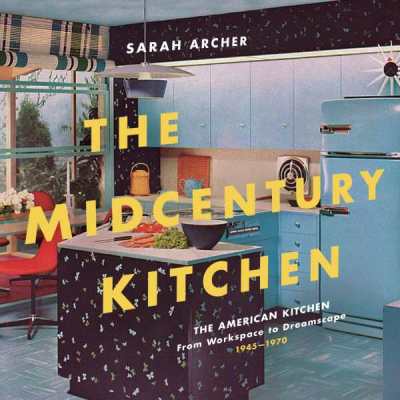

This week, we’re thrilled to revisit those early exciting years of domestic renaissance with Sarah Archer, the author of The Midcentury Kitchen: America’s Favorite Room, from Workspace to Dreamscape, 1940s–1970s—one of those rare books that causes a stir in our offices. You see, Managing Editor Michelle Anne Schingler is a midcentury kitchenware freak. So, when Sarah’s book arrived, Michelle quickly nabbed the rights to review it in the May/June issue and then forced her way onto Foreword This Week schedule so that she could commiserate about vintage Pyrex with Sarah. Okay, we’re exaggerating … but not much.

Take it from here, Michelle.

To what do you attribute the recent increase of interest in midcentury kitchens, particularly when it comes to collecting?

It’s hard to choose just one influence, but I think the middle decades of the 20th century are long enough ago now that people feel they can rediscover that style, and there’s something about the smooth surfaces and vibrant colors that seems to work well for a lot of people these days. Midcentury-inspired furniture (of which there’s a lot on the market these days) isn’t fussy, it’s easy to clean and can be easily mixed and matched with other pieces. For me personally, there’s an element of the kitschiness that makes me happy. I love that so much of the design was full of elements like starbursts and boomerangs, not trying to be low-key, cool or subtle at all. It’s the decor equivalent of jazz hands, and that speaks to me.

Are you yourself a collector? If so, of what?

I don’t usually call myself that but I’ve sort of ended up with a lot of studio pottery—that’s largely because I was the director of a ceramics studio called Greenwich House Pottery in New York some years ago, and there’s a great gallery and shop there. Now I live in Philadelphia and The Clay Studio also has a great gallery and shop … so I have some really wonderful handmade things. And I tend to accumulate things like vintage tea canisters and Pyrex mixing bowls, world’s fair commemorative plates, that sort of thing. I’ve sort of hit my limit in terms of space though, so I think I need to start collecting miniatures, or antique sewing needles or something!

Do you have a favorite Pyrex pattern, and why is it your favorite? (I collect butterprint pieces because they’re lovely and dreamy, and crazy daisy pieces because I grew up with them and they carry personal nostalgia. Also, though, I’m Jonesing for the 1960 Starburst piece on page 130.)

I LOVE the Starburst piece and wish I had one too—there are so many amazing Pyrex patterns, and I actually have a fun set of two Americana mixing bowls, one white and one brown with gold lustre, decorated with things like eagles, a hand-crank coffee grinder, a mortar and pestle, and ears of corn, all of which are supposed to evoke colonial times (I think!?). I had assumed they were made for the Bicentennial but they’re actually earlier—they were produced form 1962–71.

My boyfriend and I both love midcentury wares, but approach using them differently. He likes to be a part of an item’s story: he loves that it was once used in some other family’s kitchen and that there are inevitably stories built into it, but thinks that now that it’s in ours, it should be used as intended. I treat my Pyrex more as a relic (no dishwasher use here!), and while I’ll use a fifties piece to serve in, I’ll use it very carefully (because adding a chip would be a tragedy). On which side do you come down in this debate—should an item’s purity be preserved, or should we use things until the wheels fall off?

This entirely depends on the object. I’d say if it’s just a perfect object, I use it, and feel sad if it fades or gets chipped, but feel that it’s part of the object’s lifecycle. This is especially true of things that were mass-produced. If something is truly one of a kind and I’d be grief-stricken if it breaks, I tend to err on the side of display item.

A lot of people, when asked to picture midcentury kitchens, may think of ads or media that positioned women in heels, pearls, and aprons, their hot casseroles extended and their smiles pasted on. The frequent reaction to this is that it represents period sexism, but your book reframes such images as a matter of liberation from drudgery. Why is this reframing important?

I actually think it’s both! The underlying premise that women belong in the kitchen exclusively just because they’re female is certainly sexist, but in the context of the time, this was only just starting to be questioned. People like Christine Frederick who applied scientific management to kitchen design could be considered feminist for their time, because they believed their work would make life better for women. There wasn’t any realistic expectation that machines would suddenly do all the work and women could commit to full-time careers—think back to Jane Jetson, who has a robot maid but still identifies as a homemaker.

So I think the reframing isn’t so much about gender roles but about technology. People who aren’t old enough to remember the pre-modern-appliance kitchen (which nowadays is most people) have a hard time understanding how radical a change the postwar kitchen was for ordinary people. Imagine going from coal stoves and no running water to a gas range and a dishwasher within one generation. Sexist though it may have been, those technological changes really did change women’s lives, and in a sense they paved the way for feminism as we know it because in the most basic sense, women had more time of their own thanks to labor-saving devices in the home.

Speaking of liberation: you bring up Brownie Wise and her Tupperware parties in your book. Tupperware parties enabled many women to become independent business owners, maybe for the first time. How (if it all) were those business models and practices different from MLMs (multi-level marketing) today?

That’s a good question; I’m somewhat familiar with MLMs but I don’t think I know enough about them to answer!

You also point out that “American cooks had a complex relationship with convenience” around the midcentury—so a box mix that you had to add something (besides water) to didn’t sell as well as one you had to add an egg to. You tie this into Blue Apron, Hello Fresh, and other meal services today. How should we feel about convenience cooking?

Yes, exactly, we all seem to feel torn about meal kits! My husband and I were on a meal kit plan for a while and ultimately went back to cooking freeform because the kits impose a certain time pressure. You don’t want the ingredients to go bad so you’re sort of locked in for the week. But I also think kits that include fresh ingredients are a real godsend for people for whom shopping for and cooking with fresh food is logistically really hard, time-wise or money-wise. My feeling is, as long as most or all of the packaging is made from post-consumer waste, and the food is made from a variety of fresh ingredients, it’s win-win.

I also found it interesting that the American midcentury kitchen had such international relevance. You bring up a fascinating exchange between Khrushchev and Nixon. How did this one room become such a place of hot international debate?

Isn’t it wild? I love that exchange, especially because of the way it echoes the question you posed above about technology and sexism. Nixon essentially takes the Christine Frederick position, assuming that kitchens are a woman’s natural place, and extolling the virtues of all the stylish machines that make her life easier. Khrushchev questions the idea that women belong in the kitchen at all—which is probably not what Nixon was expecting to hear! Unlike the garage or the living room, where cars and TVs are the focus, the kitchen is right at the crossroads of gender and innovation. It perfectly captures the midcentury paradox of women’s roles, in which high-tech gadgets are being sold to eliminate the very domestic work they’re supposed to devote their attention to. So manufacturers and advertisers had to walk a fine line not to make it all seem too easy, i.e., “she still has to vacuum and load the dishwasher, it’s just easier now, so she can do it in pearls.”

Michelle Anne Schingler