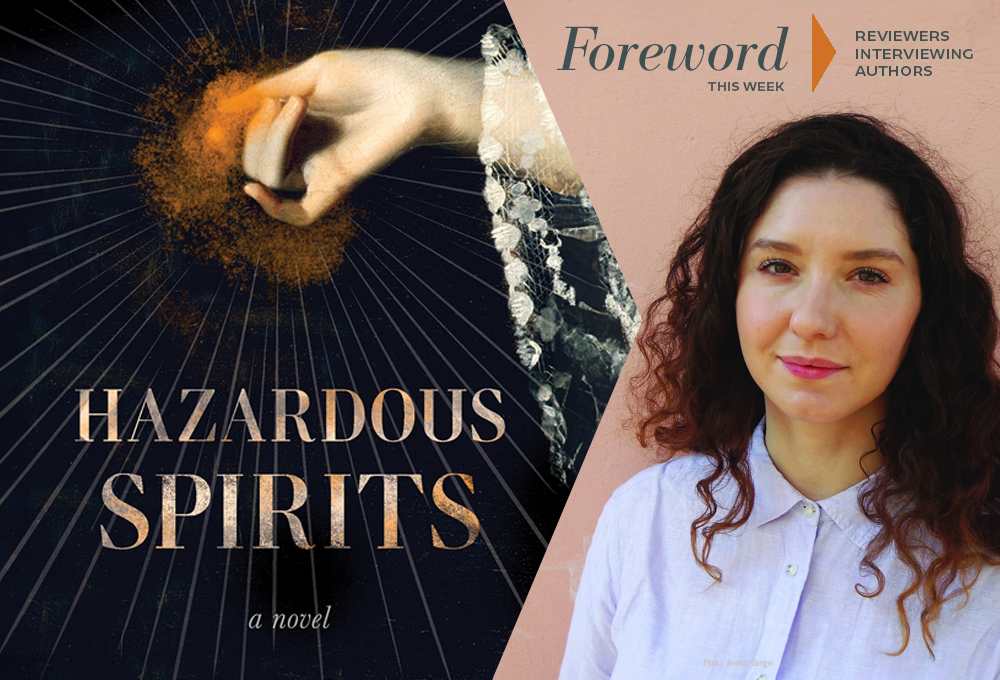

Reviewer Michelle Anne Schingler Interviews Anbara Salam, Author of Hazardous Spirits

An “intoxicating novel” about spiritualism in Edinburgh’s Roaring Twenties, Anbara Salam’s Hazardous Spirits earned a glittering review from Foreword’s Editor-in-Chief Michelle Anne Schingler. The two of them were more than happy to connect for this visionary conversation.

Your lens into the spiritualist movement is a high society one in post-World War I—and post-flu epidemic—Scotland. Why were communities such as Evie’s so susceptible to spiritualism’s pull?

In my understanding, Spiritualism was popular across large sections of society, not just the more aristocratic circles, but I was interested in exploring how what is considered “eccentricity” for the more affluent, can be stigmatising in less wealthy social circles. Spiritualism is a particularly interesting movement because for some people, attending seances was little more than a tantalising parlour game, while for others it was a religious practice deeply tied to the Christian church. In Hazardous Spirits, Evelyn is drawn into a high-society circle traumatised by the effects of WWI and still struggling with the repercussions, many years later, and Spiritualism allows them the “permission” to explore these feelings in a way that the traditional “stiff upper lip” mentality of post-Edwardian Scotland wouldn’t typically indulge.

Evie doesn’t want to believe, but she does want to keep her husband happy: for her, spiritualism is at first about indulging him. What else pulls her toward believing that the mediums she interacts with are on the up-and-up—and what, ultimately, prevents her from going all-in?

Edith Wharton wrote, “I don’t believe in ghosts but I’m afraid of them,” and ultimately I think that captures Evelyn’s feelings about Spiritualism. There are moments in the narrative when she does fully believe in the gifts of the mediums, but there is a difference between committing to an entirely transformative worldview, and being convinced in the moment.

Your book evinces thorough research into the period’s charlatans and charismatics. Did any particular stories stick out to you from the era?

The illustrious and controversial career of the Scottish-American medium, Daniel Douglas Home (1833–1886) is a particularly interesting one. He claimed powers of mediumship, levitation, and telekinesis, and in his autobiography alleges that as a baby his cradle was rocked by an unseen hand of a spirit. During his career he drew criticism from Harry Houdini, investigation from Michael Faraday, prompted satirical poetry from Robert Browning, and elicited support from Arthur Conan Doyle. What I found so compelling about Home is the tornado of speculation and scandal that surrounded his vocation as a medium, and how all that controversy only seemed to fuel his popularity.

Do you see any parallels between spiritualism’s pull then and any contemporary movements—either New Age or elsewhere? And, if so: what’s the perennial element of the draw toward this kind of magical thinking?

Spiritualism is still a movement with active practitioners and churches, however, at the peak of its popularity it offered promises of supernatural intervention at a time when more traditional religious beliefs struggled to offer meaningful solace for those reeling from the global scale of death and suffering. Although Hazardous Spirits is set almost exactly 100 years before its publication date, we are still living in a moment characterized by interest in the mystical: tarot card readings, crystal healing, popular astrology, essential oils, “manifestation,” meditation apps. All of these esoteric or esoteric-adjacent rituals are quite inward-looking practices that sit well with our contemporary mandate to nurture and focus on the self.

Perhaps this is a reaction to an out-of-control climate and economy, or perhaps it’s a happy confluence of consumer capitalism and a desire for enchantment. The perennial appeal of magical thinking is likely how little sacrifice it demands from its devotees, with seemingly cosmic rewards. It’s like a form of spiritual snacking for those who want to feel guided without the requirements of commitment or community.

You have a background in theological studies. Speaking as an expert, how would you advise Evie at the cusp of her entering spiritualist circles?

I’m absolutely not in a position to give theological guidance to anyone, no matter how fictional! A sensible approach though for anyone contemplating a spiritual movement is to think carefully about how adherents are benefitting from their practice and their community. This can be very illuminating!

What are you working on next?

I’m writing a Gothic mystery set on a Scottish island during the Cuban missile crisis. It’s the most “modern” novel I’ve ever worked on, and I’m secretly enjoying not having to pause writing to go down a research rabbit-hole about historical streetlamps or buttons every few paragraphs!

Michelle Anne Schingler