Reviewer Peter Dabbene Engages with John Carlin, Author of Mandela and the General

Leadership—if you possess the right skills, there’s some job openings in that department, especially in the government sector. Alas, the world is sorely lacking for a few good presidents and prime ministers.

Throughout history, great leaders made do with a remarkable combination of ambition, intellect, patience, charisma, and an abiding sense of the greater good. Toughness too proved to be important, especially in the most trying times. Indeed, perilous moments seemed to bring out the best in Lincoln and Churchill, for example, and more recently, Nelson Mandela, the anti-apartheid hero who deftly kept South Africa from descending into a full fledged race war/civil war.

Extraordinary as he was, Mandela didn’t do it alone. He needed an influential kindred spirit in the opposition, and he found him in General Constand Viljoen. The two men somehow kept the most radical of their followers from resorting to violence.

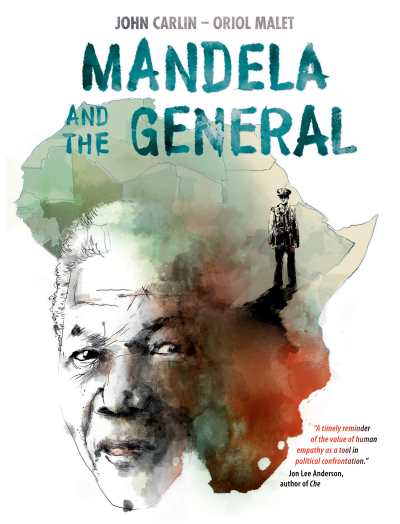

This week’s Foreword This Week brings us John Carlin, the former South Africa bureau chief for the Independent of London from 1989 to 1995. Carlin spent time with both Mandela and Viljoen, and he tells the gripping story of their relationship in Mandela and the General, a newly released graphic novel reviewed by Peter Dabbene in the November/December issue of Foreword Reviews. The good people at Plough Publishing House helped us get in touch with Carlin for an email interview and the rest, ahem, is history.

John, as a correspondent in Johannesburg from 1989 to 1995, you certainly had a great vantage point to observe the turmoil and transition in South Africa. When did you first consider writing a book on the subject? Why a graphic novel, rather than a traditional non-fiction book?

This book came about after my French publisher, Le Seuil, asked whether I had a story about Mandela that captured his political genius vividly, and with emotional force. It took me precisely three seconds to mention the story of Mandela and the General, which had long lingered in my mind. It took them maybe five seconds more to reply “let’s do it.”

Telling the story in graphic form appealed to me immensely as a new writing challenge and as a vehicle for reaching new audiences. As someone who had the immense privilege and good fortune to get to know Mandela well, I feel I have a duty to pass along my knowledge to future generations. Also, of course, I do write books for a living, so I seize my chances when they come! I’d also like to note that it was a pleasure and an education to work with my very, very clever French editors and with the brilliant and doggedly industrious illustrator, Oriol Malet.

General Viljoen and his brother, along with Mandela, are portrayed in the book as very strong-willed people. Was it difficult to arrange interviews and get them to speak freely about their pasts, or were they forthcoming and eager to talk? Did anyone feel the need to “set the record straight”?

Funnily enough, it was not difficult at all. It helped that I approached them several years after they had both abandoned the political stage. They were both as I expected them to be: serious, straight-talking men of honor and integrity who, by the way, felt no vain imperative “to set the record straight.” There was no righteous vindication, no blowing of their own trumpet.

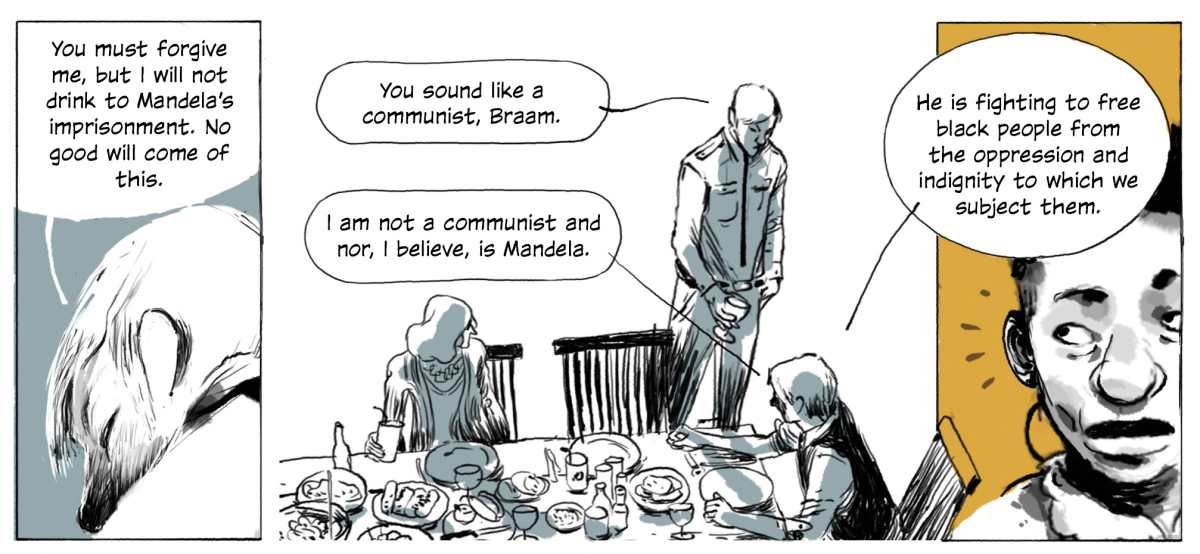

What I had not expected was how shockingly identical the Viljoen twins were. Constand was more straight-backed, as befits a military man, and Braam more shambly, but they were the same height and and their faces were indistinguishable

One of the book’s highlights is the dramatic secret meeting between General Viljoen and Nelson Mandela. How much of that conversation was recounted by those men in interviews, and how much re-imagined by you?

The conversation was recounted to me both by Constand Viljoen, who I only met once, and by Mandela, with whom I met many times. People who were close to Mandela and had been in his home that day provided more information. Naturally, I had to re-imagine the precise wording, but I am confident I have been faithful to the content and spirit of the exchange.

What I find most interesting about this story is that it shows individuals in positions of power making the decision to avoid war, when the people they represented, as a whole, might have plunged in headfirst. It’s a somewhat contradictory idea for those of us who live in countries with a strong tradition of democracy. Do you think the message carries over to other, more common political situations today?

Interesting observation. Yet however strong the democratic tradition, there is always a need for principled leadership. In fact, the two go hand in hand. A leader, after all, is elected to lead, to set the course—if not, he or she is not a leader. This means that, on occasion, the leader must have the moral courage and clarity of vision to stand up to the clamor of the multitudes and speak and act as he or she thinks. Viljoen had to do it once. Mandela did it all the time, both within his inner cabinet and with vast crowds. I was present at a sports stadium in 1993 where 20,000 of his own African National Congress supporters demanded Mandela give them weapons to fight their enemies. “We want arms! We want arms!” they shouted. Mandela argued with the crowd, explained to them that violence might provide short-term satisfaction but would be ultimately self-defeating and lead to chaos. At one point, he even said he was prepared to quit as their leader if violence was the method they chose to pursue. That shut them up. By the end of the speech—or rather, dialogue—Mandela had won the crowd over. They accepted his demand for peace and they chanted his name in triumph, celebrating his victory over them.

Mandela is widely praised for his efforts to overcome apartheid, but until I read your book, I was largely ignorant about the General’s key role in bringing about a peaceful transition in South Africa, as well as the important influence of his brother Braam. What is their reputation, their legacy, in South Africa today?

Mandela won a decades long war, metaphorically speaking; the Viljoens, by contrast, waged just the one political battle—a very important one, for had the outcome gone the other way, all the conditions were there for terrorist violence leading to civil war. The Viljoens proved critical in the achievement of Mandela’s one overwhelming goal upon coming to power: laying peaceful and solid foundations for South Africa’s new democracy. Have the Viljoens received the public acknowledgment they deserve? Not enough, I’d say. I am sure they will after they die: the obituary tributes will see to that. But hopefully this book will help to bring forward the day when their contribution receives the applause it deserves. Though, having said that, I know that neither of them feels any need for public recognition. They are men who feel they did their duty by their country, no more nor less.

Do you have any upcoming projects that you’d like to mention?

None that I’d like to mention, thanks! Best not to open the oven door until the goose is cooked.

Peter Dabbene