Reviewer Peter Dabbene Interviews Peter Dunlap-Shohl, Author of Nuking Alaska: Notes of an Atomic Age

In 1945, the US succeeded in its dream of creating a nuclear weapon so powerful all other nations would cower. We used it once, then twice, in Japan, to kill 200,000 and force an unconditional surrender, ending WWII. And we continue to use an arsenal of much more destructive nuclear weapons as a deterrent, even as a handful of other countries have joined the nuclear club.

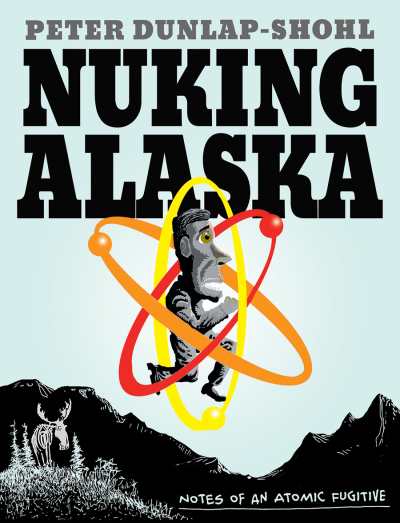

In those first giddy years and decades after the US mastered nuclear technology, a few visionaries were intrigued by the idea of using nuclear explosives in peacetime—to instantly create a harbor in Alaska, for example. In fact, Alaska was ground zero for a lot of nuclear tomfoolery we come to find out from today’s guest, Peter Dunlap-Shohl. And many of the tales he tells in his splendid new graphic novel Nuking Alaska will chill your bones. Yes, we’ve come close to nuclear disaster more than a few times.

Peter Dabbene reviewed Nuking Alaska in Foreword’s May/June issue, and his enthusiasm compelled us to connect the two Peters for the following chat.

The long history of nuclear weapons in Alaska was largely unknown to me until I read your book, and I would suspect that ignorance is shared by much of the population of the lower 48 states. Are these stories well known in Alaska? Your book mentions a University of Alaska oral history project on Cold War Alaska, but are incidents like the 1964 earthquake and the high-stakes missile cleanup that followed, or Edward Teller’s proposed “nuclear excavations,” or the detonation at Amchitka Island regularly taught in schools there?

The best-known of the stories I tell in my book is probably the tale of Edward Teller’s attempt to nuke a hole in Alaska’s northern coastline to create an instant harbor. It was meant to be a demonstration of the potential for peaceful use of atomic power … unless you happened to live near the proposed blast area, in which case it wasn’t easy to see it as terribly peaceful.

The story was uncovered and told brilliantly by University of Alaska Fairbanks researcher Dan O’Neil in his book The Firecracker Boys. It has been the subject of a documentary film as well.

The Cannikin test on Amchitka Island was a big deal at the time, an international controversy, but is largely forgotten today except by workers who were contaminated somehow and became sick while working on the clean-up of the island following the test of the hydrogen bomb.

The Nike missile fiasco following the 1964 earthquake is practically unknown. I stumbled across the story while on a tour of a different Nike site where a friend who volunteered there to preserve Alaska Cold War history mentioned it to me. There have been a small number of newspaper accounts of the ’64 quake incident and of the Amchitka Island workers, but the number of stories about these events that have appeared in the local press could probably be counted on the fingers of one hand. And, of course, it was hushed up at the time.

Alaska has a large population churn. People come North looking for adventure or trying to escape their past, then find the winters too tough or the distance from family too great and they go back to the South 48 states. The high population turnover means that many people who live here often don’t have a strong grip on local history.

Nuking Alaska combines your personal experiences and perspectives with a wider look at these events, and the book includes extensive notes and reference links. How long did you work on this project, and when did you first get the idea that the subject matter might make a great graphic novel?

I worked on this book at least since 2017, when a section of it was published by The Nib, Matt Bors’ website for opinion and non-fiction comics, so at minimum, six years. I got excited about the idea of telling the story of Alaska’s experience with nuclear risk when my friend Jim Renkert told me the story of the 1964 earthquake near-disaster. I have seen little coverage of that aspect of the earthquake and I thought it would be useful to let people know how close we came to disaster, how my little old hometown Anchorage could become “The most dangerous place on Earth.” And how many different forms the nuclear threat to Alaska would take, everything from Soviet bombers to “mad scientists” to opportunistic politicians.

Edward Teller comes off as quite a villain in the book, perhaps even more so than Nixon and Kissinger, who wanted to use nukes to shorten or end the war in Vietnam (one would think that Teller, as a scientist, would have had a better understanding of the risks involved than two politicians). No one can say exactly what Teller was thinking as he made his decisions or pressed for support of them, but what is your sense of the man? Was he simply a scientist who was blinded by optimism and hope? Or was he fully aware of his lies to the public and the risks inherent in his proposals—a man who sacrificed his morals to ambition?

Teller was a complicated man. As a Jewish refugee from European fascism, he had more reason than most to be worried about the fate of the West and the world in general in the 1930s and 40s. But his fear of what evil men could do led him to make some decisions that I find difficult to forgive.

He had a huge talent for physics and a huge ego to match, which brought him into conflict with J. Robert Oppenheimer, the director of the US effort to build an atomic weapon before the Nazis could.

For Teller, the ends justified the means. This led him to pursue questionable policy goals, for instance, Nuking Alaska, and advocating the treaty-busting and destabilizing “Star Wars” missile defense system.

He also practiced the politics of personal destruction, raising questions about his rival Oppenheimer’s loyalty to the United States, which destroyed Oppenheimer’s career after the end of WWII. (An act which left Teller an outcast among the few people who could understand him, the rarefied fraternity of nuclear physicists.)

Against all that we have the fact that he played Bach on the piano, and taught Sunday school after he retired. File under “villain.”

Your career as a single-panel political cartoonist seems to have meshed extraordinarily well with this subject matter, but a longform graphic novel is a very different form of communication. Having done both, do you have a preference? What are the pros and cons of each?

The two forms are very different. Political cartooning is a sprint; longform graphic novels are a marathon. Each has its pleasures and frustrations. With editorial cartoons you have those never-ending daily deadlines, but when you go home for the day, you are done. You also have a variety of subjects over the course of a week that you better be semi-knowledgeable about if you hope to say something intelligent about them, from the intricacies of campaign reform, to the tragic questions surrounding guns in America, to the theological complexities of the abortion debate.

The graphic novel draws on a different set of muscles. Instead of the quick hit of a political cartoon, you have the slow burn of dissecting a single topic or storyline, digging deep instead of skimming the surface. It depends less on daily inspiration and more on daily perspiration. You need a topic that will sustain your interest over the course of years, and you will need to get used to delayed gratification.

With the graphic novel you have time to polish the work to a high degree (not that my work is highly polished), and the graphic novel has a longer life than the daily political cartoon, which depends on the current news environment for much of its impact. The graphic novel is more self-contained, and comes with a longer expiration date.

I enjoy working in both forms, but I find as health issues affect my efforts to do the work to the best of my ability, the more leisurely pace of the graphic novel suits me better. Which is a good thing when you check the demand for political cartoonists in the current job market.

One of the most affecting scenes in Nuking Alaska is the multi-page depiction of the 1971 Amchitka Island blast. How did you arrive at that approach? Did you ever consider a simple, single panel image of an explosion, or did you know from the beginning that wouldn’t suffice for what you wanted to convey?

I thought that a single page would not carry the weight of a 5-megaton nuclear explosion, the largest ever performed in the history of US atomic testing, especially after having used the image of a mushroom cloud several times already in the text. So I developed the idea of the multi-page explosion which unfolds almost as if it were in slow motion to attempt to portray the power of the multi-megaton blast.

Your book shows some of the catastrophic effects of using nuclear bombs, and it’s a well-timed lesson, arriving in a year of increasing nuclear threats from Putin’s Russia, an ever-bolder North Korea, and China, which seems ready to significantly expand its nuclear weapon stockpile. While we can hope that much of this is political brinkmanship, do you think that leaders truly understand the impact of the nuclear weapons they use to threaten other nations?

God, l hope so.

In 2015, your graphic novel My Degeneration, an account of your battle with Parkinson’s disease, was published. The art in Nuking Alaska is outstanding, and shows no indications of physical challenges to its creator. How difficult is it for you to draw at this point? Can you talk about your drawing process, and how it’s changed over the years? What projects does the future hold for you?

Thanks! My struggle to maintain my ability to work as a cartoonist has been a humbling journey. I developed severe pain as a result of combining bad drawing board ergonomic habits with the muscle stiffness that comes with Parkinson’s disease. My resourceful doctor finally ran out of ideas that could keep me drawing with acceptable levels of pain.

I was never a fan of computer graphics, but it seemed to me if I was able to sit with my head level looking at a computer screen, my body would avoid the stress that was causing my pain. The doctor agreed, we tried it and it worked. I went from stretching every fifteen minutes to working steadily for hours without pain.

The only problem was learning Photoshop, which was an epic struggle for me. Fortunately, my wife, Pam, is a Photoshop wiz and was able to bail me out when I got in trouble. Which was frequently. But I eventually got the hang of it, and a door opened on a new world of creative possibilities as I was able to work with color, sound, and even animation. And then there’s the magic of the “undo” button, which gives you the ability to take risk-free risks. If something goes awry, just undo it.

I can’t imagine how I could compose a graphic novel on paper today, the lettering alone would end me.

As far as future projects go, I am about two thirds of the way through a follow-up to my first book which will contain updated material to reflect advances in dealing with Parkinson’s disease and includes new thoughts on having Parkinson’s that I have developed over the years since creating My Degeneration. After that, we will have to wait and see.

Peter Dabbene