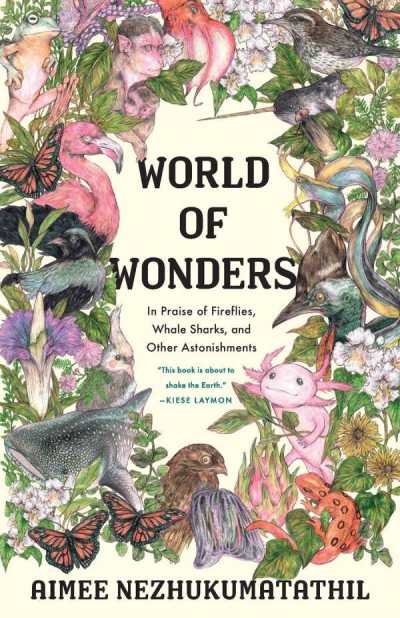

Reviewer Rachel Jagareski Interviews Aimee Nezhukumatathil, Author of World of Wonders: In Praise of Fireflies, Whale Sharks, and Other Astonishments

Whenever it’s a scorching, sweaty August in our soul; whenever we find ourselves uninspired and lacking the energy to engage with the world; whenever the urge to lash out at friend and foe alike takes hold; we know that it’s high time to get to the beach or the shady trail as soon as we can. Like Ishmael in Moby Dick, we know that we’re in need of some nature TLC.

Don’t despair if you can’t get away soon, this week’s FTW brings you a virtual nature fix. Meet Aimee Nezhukumatathil, author of World of Wonders, and one of the most beguiling writers we’ve ever seen. The daughter of a Filipina mother and Indian father, Aimee’s family moved often in her childhood and she grew accustomed to being the “new girl” and the “brown girl.” She coped by escaping outdoors. As she says in the interview below, “I found solace and comfort in studying and observing the natural world around me, how I couldn’t truly feel alone when there were such astonishing creatures and plants around me.”

We were alerted to Aimee’s extraordinary life and talent when Rachel Jagareski delivered her review of World of Wonders with a rare star in the pages of Foreword‘s July/August issue. In the review, Rachel says Aimee’s “entrancing essays are a reminder to spend more time outdoors wondering at and cherishing this ‘magnificent and wondrous planet,’” and we knew an interview was just what the dog days of summer needed. Thanks to Milkweed Editions for helping to make it happen.

Rachel, you’re on.

Your book is a tasty mix of poetic imagery, introspection, memoir, and intriguing biological facts. Where did you glean these fascinating nuggets about the plants and animals in your book?

It’s been a lifelong–I hate to call it a practice because that sounds intentional, but it’s the closest thing I could call it besides it’s just what I do. I’ve been reading about the planet and shells and creatures and trees, etc., since I was old enough to check out my own stack of science and nature books from the library. I also get much of this from field research—swimming with whale sharks, visiting botanical gardens and zoos with my sons (pre-pandemic!), even touring my parents’ garden always provides much learning.

While some of your subjects are traditionally lovely or cuddly, like peacocks and fireflies, I admit to more affection for your portraits of less popular flora and fauna. The Corpse Flower is splendidly putrescent and architectural, and I was mesmerized by your description of the Vampire Squid, gliding through inky waters for “a meal of marine snow.” What are your favorites from this collection and why?

Thank you so very much! It’s so hard to choose but I can say the Vampire Squid was the toughest to write as I’m not hiding behind any veil of “persona” as I often do in my poetry, and the southern cassowary was the one that went through several revisions because while it’s one of the most terrifying birds on the planet, I was also so very charmed by how striking it looks as it strolls across a beach, for example, and wanted so much to capture that vibrancy on the page.

The connections between incidents in your unique life and attributes of your natural world subjects make this book distinctly memorable. You poignantly relate the challenges of your many childhood moves, of being a Filipina-Indian rara avis, and of being the constant new girl at school (never mind that one of your mother’s medical jobs required residence at a Kansas mental institution). The scenes of your youthful cephalopod year—darting away from others to shield yourself from the sting of casual racism and xenophobia—is especially relevant in light of renewed Black Lives Matter activism and discussions about race and social justice. Are you finding additional interest in your book because of these themes?

I think I’m definitely not unique in terms of wanting to fit in and feeling a bit like a misfit during my teen years, but I think what I hope comes across is how much I found solace and comfort in studying and observing the natural world around me, how I couldn’t truly feel alone when there were such astonishing creatures and plants around me. And yet, as an avid reader, I never saw anyone who remotely looked like me featured in any of the books about the outdoors that I loved so very much. It’s a very strange and yes sad thing to grow up having never seen yourself in books or movies and I guess this was born of that idea but it certainly wasn’t the driving push behind these nature essays. First and foremost I wanted to gather up a collection of plants and animals that made me fall in love a little bit with the outdoors, to celebrate the bounty and beauty and darkness of impending endangered animals all with a lens of navigating time outdoors as an Asian American who has (gasp!) crushes, who loves to read, who watched her parents work so hard during the week but who always made a garden or hikes outside such a place of comfort and safety.

You relate to the homing instincts of the Red-Spotted Newt when you describe how comfortable you felt when your family moved South for your teaching position at the University of Mississippi. You vividly describe “a shift in my body … like tiny magnets in me lined up and snapped to attention.” Is this “pull to come home” derived from the region’s greater social diversity or richer natural landscape, or both?

Absolutely both! Mississippi is perhaps one of the most complicated states in the country but I find it is also a place of such fierce love and joy. Oxford is home to so many progressive people who work so hard to make this a place we can be proud of, where people of all backgrounds are welcome. It has a long way to go to make this a more loving place to the Black community in particular, but I can tell you I’ve never been asked the dreaded, “What ARE you?” question here and I feel much better/safer about raising a family in the south than I ever did when I lived in western NY.

Your essay capturing your young sons’ volley of questions during a birdwatching session was another masterpiece of emotive prose. You intersperse their exuberance and quickly-shifting attention spans with their questions about why some white people don’t like brown people and whether they have “good camouflage” even though they are “mixed.” Imagining your unwritten responses is powerful. Aside from the topicality of birding while black/brown, how are you preparing them for living in a culture where white privilege is still dominant?

Oh this is such a good question. I’m sure I mess up lots of times, but the one thing I’m so proud of is that my (white) husband and I have always talked and kept lines of communication with our sons wide open. They know there’s not a single subject to be afraid of asking us but also from the get go, we have talked about moments where I get treated differently than their father—and most often, thankfully, it is my husband who points that out as a matter of fact and why it is so wrong. He is just such a model for them in every way possible to navigate a school where they both have a rainbow of friends.

We very purposely have gathered a vast selection of books that feature characters of all abilities and backgrounds—my dream library as a kid! So since they could read they were already imagining and having empathy for people with backgrounds different from their own. The art and TV shows they consume are also full of people from different backgrounds. Depending who they are with, my sons might “read” to others as 100 percent white, but they have been looking out for others of all backgrounds since they were in preschool. Now if I could only get them to stop leaving wet towels on the floor.

Your final essay sounds a hopeful message about how we might yet avert catastrophic climate change, even as you note that your students seem to have an ever-decreasing knowledge of the natural world. With the world’s attention presently gripped by the coronavirus and economic and social tumult, do you feel positive about the prospects for avoiding drastic climate change?

I have to feel like there is hope, at least. But that would take a global reckoning, a global pledge to love and help things and people that don’t directly benefit us financially. Could it happen? I hope so, not just for the sake of the next generations, but for what I hope is the inherent goodness of kids who are so full of wonder at the planet and its inhabitants, until someone tells them it isn’t cool anymore. But I’ve traveled all over the world to teach poetry to kids and I’ve yet to meet a group of kids that don’t care for the planet. It’s trying to keep that fire and tenderness alive throughout our whole adult lives that is the tougher job, but I’m not giving up on hope, and I’m going to do my best to help adults remember what it was like to have a sense of wonder.

What other writing projects are you currently working on?

I don’t want to give too much away but I’m working on a hybrid project that encompasses beauty products from around the world, a natural history of snakes, and a dash of memoir thrown in!

Rachel Jagareski