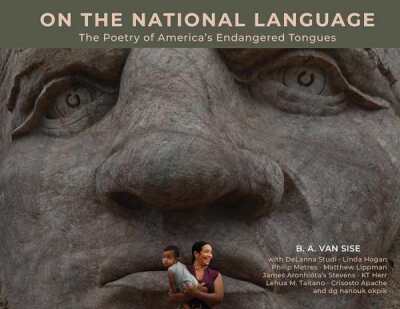

Reviewer Rachel Jagareski Interviews B. A. Van Sise, Author of On the National Language

“It is a hope that someone, somewhere, might see it and be inspired; find one impossible word and want to learn another and another.’’ —B.A. Van Sise

You know Duolingo, Babbel, and Berlitz, but today you’re going to hear about the best foreign language program of all? That would be Van Sise, where you learn only the good stuff from languages you didn’t even know existed, some that don’t even bother to separate nouns from verbs—it’s all a lovely mind riot—and many, unfortunately, with only a handful of speakers still alive.

Here’s a sampling:

tekariho:ken, between two worlds—Mohawk, still spoken in eastern Canada and upper New York.

kapará, worse things have happened—Ladino, a few speakers around the US.

onirique, something that comes from a dream—Houma French, Louisiana.

koyaanisqatsi, nature out of balance—Hopi, across Arizona.

amonati, something you hold and keep safe for someone else—Bukhari, spoken in Brooklyn.

ma’goddai, feeling when the blood rises that makes you act both violently and lovingly—Chamorro, Guam, Pacific islands.

ny’thkvekuum, I’m going back to where I came from—Maricopa, around Arizona.

dena’nena’henash, our land speaks—Koyukon, Alaska.

opyêninetêhi, my heart is taking its time—Sauk, Midwestern US and Coahuila, Mexico.

There isn’t an app to learn these and many more delightful words but the Van Sise dictionary—On the National Language—will make you want to forget your English. Rachel Jagareski held on just enough to pen a beautiful review in Foreword’s September/October issue, but we could tell she wanted to let loose with some sixty-plus-letter words that would turn our brain inside out—in a good way. Next issue, Rachel.

Speaking of fascination with foreign languages, here’s a collection of translations from Foreword’s September/October issue. Then, take a moment to have and to hold your free digital subscription to Foreword Reviews.

What was the genesis for this project?

This project, like all of mine, found me more than I it: I almost always start with something else and suddenly something more important runs up and tackles me. In this case, I’d actually been working on a project called Sooners Later, which was … sort of a plucky landscape project.

I’d fallen in love with Oklahoma and in particular its neon. There’s a big Americana, Route 66, Leave It to Beaver thing going on there where the endless undulating grass of the prairies is punctuated by neon signage telling you to sleep in some particular hotel or dive into a special onion-laden hamburger. Drive past the bison to roller skate right here. That sort of thing.

I was out there working on it in the dusktide, driving my then three-year-old godson to Tahlequah to take him to the Cherokee Heritage Center. He’d fallen asleep in the back seat but up in the front I had the radio on and the actor Dwayne Johnson was giving an interview to promote a film, and got to this really heartfelt moment talking about how there was a hole in him. Despite his success, he had a Samoan mother but couldn’t speak Samoan, and wasn’t as deeply enmeshed with the culture as he’d like. A light bulb went off, thinking about the language; in spite of a couple of decades working as an artist and author, my degree is actually in linguistics and I am an endangered language speaker. My first book had been about poets and poetry; perhaps it needed a sequel, as it were, exploring the poesy of language itself—so much of our culture is tied to language; so much of our values is tied up in our vocabulary. Perhaps, it was something worth exploring? And then it was off to the races.

How did you locate the various endangered language speakers?

In the beginning it was primarily through tribal/national and cultural diaspora organizations; the project’s not explicitly Native, but it’s about endangered languages in America and so many of the folks I feature are Indigenous language speakers and revitalizers. In the beginning I had a big challenge in that a lot of the tribal/national governments I’d reach out to would flat out lie to me and suggest that I photograph their main political figure—their chief/governor/president/etc.—who almost without fail didn’t know more than hello in the language but loved having his—and it’s his—picture taken.

A few plates in, I met the young-ish fellow running the Chickasaw language revitalization program and realized, once again, that there was a better story here: not one about the past, but about the future. I sorta changed gears towards revitalizers, and that community is pretty well-integrated with itself: like poets, like photographers, everybody kinda knows everybody and it became about personal connections. I’d photograph one person and say, “hey, do you know anybody who’s working to revitalize XYZ?”

There is so much humor and joy in the visual poems. Is that part of your art aesthetic or was it naturally captured from your subjects?

That’s me. Part of it is that I absolutely wanted to eschew—especially with the Native folks—the trope of stoic, acerbic presences that dominate the White gaze. But a lot of it is that I just love a bit of magic; as a teenager I got really into stage magic. I’ve not turned a card in twenty years, all my hats are rabbitless, but I’m a life member of the International Brotherhood of Magicians and I like to put a little of that magic into my visual work. In general—and this speaks to your next question—the image concepts come from me, but the collaborators and I would chat about it beforehand.

How did you select the words for your photos and the edifying and eloquent prose and poetry that punctuates the book?

Often the words are suggested by the collaborators and the image concepts are suggested by me, but this isn’t universal. There are definitely pairings where I suggested words—I’ve got books and books for each and every one of the languages in here, you’re crazy if you think I don’t—and I kinda did the same thing I did with my Children of Grass exhibition, where I’d raid every book selected poets had written and suggest things that I thought might make for interesting visuals.

The other turn of the coin is true, as well—there’s absolutely image concepts where the collaborator had something in mind and I’d try to get it close to where they needed. And then there were larks that turned up during the shoots: while Geneva’s daughter Jan was putting her in her gorgeous regalia for the Comanche image, Geneva kept saying, “I am tired of being beautiful” and I pulled Jan aside and said “hey, listen, this is a poem.” While photographing Barbara Amos in Alaska, a pod of freaking whales showed up and how could we not? Barbara’s reaction is real; the one you imagine from me behind the glass is, too.

The poetry is just … it feels really important to me to have other voices beyond my own in my work; I’m not an island.

My first book was a collaboration with Mary-Louise Parker, who is well-known as an actor, but is more knowledgeable about poetry than even many poets, and Invited to Life (portraits of Holocaust survivors) has Neil Gaiman, Mayim Bialik, and Sabrina Orah Mark talking about topics related to their interests and various tangents. Here, I wanted people in these communities, with these heritages, to respond, and for the most part I tried to find poets/writers who had that connection in their heart but maybe not their endangered language hidden under their tongues. (The exception is Lehua Taitano, who is also the sitter representing the Austronesian language Chamoru.) I know and like James Stevens and dg okpik (writers who are featured in the book) very much; the others were relatively strangers to me and I told them and meant it that to work with an artist is to trust an artist, and gave them free reign to have an open voice in my book.

What are some of your favorite words from the book?

I’m very, very fond of the two that open the book: tekariho:ken, the Mohawk word for “between two worlds,” and puppyshow, the Afro-Seminole Creole word for “showing off behavior.” One is transcendent; the other speaks to the realities of our characters. I also love, though I got a little cheeky with it, the image of Menny Bruk. I’d searched for someone like Menny—it was important to me to show that the people engaged with these languages don’t always look like you’d think, aren’t always where you’d think—and used a word that many may be familiar with, schmutz, meaning “dirt that moves,” defining it from Leo Rosten’s delightful Joys of Yiddish written like fifty years ago.

That’s one where I came in with the word and pitched Menny’s father on the whole thing top to bottom: “listen, your son is a young Black Chasid in rural Montana, and I think it’s beautiful but also let’s have some fun with it?” I reached out to a woman running a ranch that raises and trains rodeo horses out there—that’s her galloping past in the background—and you should’ve seen her face when a bunch of Orthodox Jews—hats, tallit, the whole thing—came walking through the rolling dust onto the ranch.

You write that while there is good work being done to revitalize endangered tongues, this work is being done “in an America that struggles to reckon with its haunted past and its nebulous tomorrow, a confused nation at the crossroads of a pivotal moment.” Are you hopeful that some of the most endangered North American languages featured in this book will find new speakers and grow in the future?

I’m really optimistic, actually, but with an asterisk: it’s hard to define a language as dying in our modern era since a lot of folks are pulling languages out of the soil that haven’t been heard for a very long time. And so, there are folks here trying to save their languages from the brink of silence that … it’s the real world, they might not succeed. But their colleagues are exemplifying what Bruce Springsteen sang about years ago: maybe everything that dies someday comes back. I’ve seen too many people—especially young people—with such tremendous enthusiasm, that it’d be difficult to be anything but hopeful.

What are some other projects that you are currently developing?

Last year I had an uncommon, horrific reaction to an antibiotic that left me without the use of my legs for about nine months, and I used the time to write a novel. Cry, and write a novel. Sob, and write a novel. But the novel, Nameless Animals, is beautiful and I’d been wanting to write it for years (sometimes, the work finds you, after all). It’s historical fiction marked by three successive incredible documents from the lives of two of my very real ancestors. Theirs is a girl next door story except this: he was a Libyan emigré in Italy who spends his entire life saving to purchase the Black African enslaved woman his neighbor owns and then immediately free her. A month later they marry with only freedom for their dowry. And so, I wrote a novel that begins with that germ and plants a much larger tree: There’s excitement! There’s murder! There’s dance numbers! There’s kissin’! (There are no dance numbers.)

My agent is shopping it around right now.

On the photo front, I’ve got two projects underway simultaneously: One about the changing climate of America, undertaken with a nonpartisan think tank called Capita. The other—well, I’ve been working on the single most important (to me, personally) work I’ve ever done; it’s called Memory Palace and it’s about prison. In my exciting, perhaps misspent youth, I got myself into what we’ll euphemistically call a little bit of trouble with the law and I’ve been working on a project that, like Children of Grass and Invited to Life and On the National Language, puts language and experience at its forefront.

Rachel Jagareski