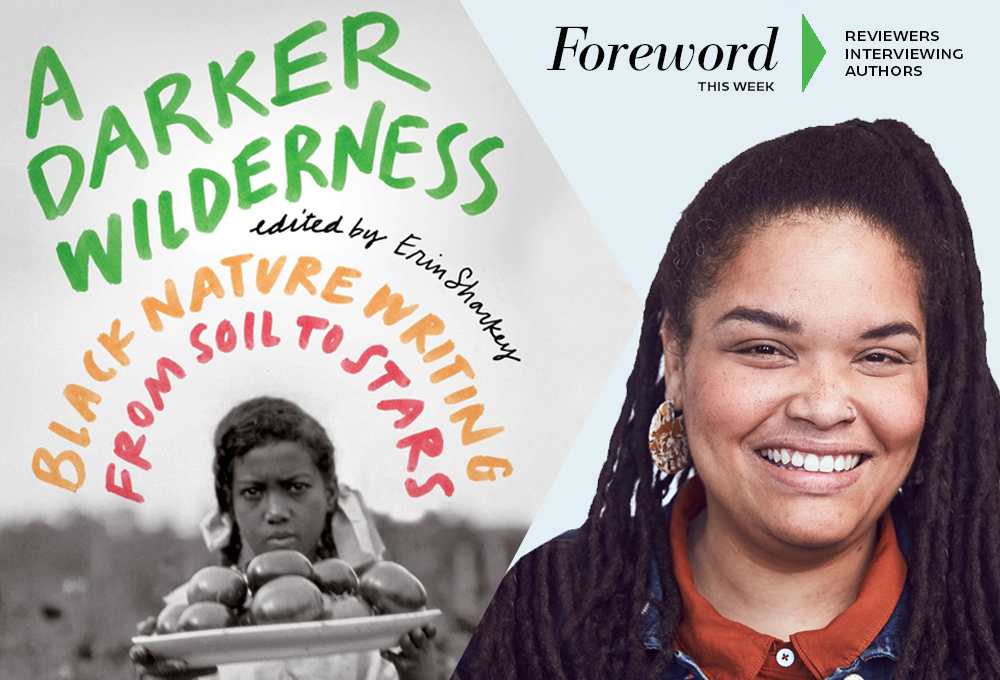

Reviewer Rachel Jagareski Interviews Erin Sharkey, Author of A Darker Wilderness

Over the recent years, we’ve been elated to see a surge in the number of nature-related books reaching our offices, and we’re doing everything we can to help those soothing books find their way to readers looking for a bit of relief from their over-stimulated, screen-filled lives.

This week’s featured book, A Darker Wilderness, fit that bill but also forced us to realize that the nature writing we see—the books that get published—are rarely written by people of color. So,

this extraordinary collection of essays from Black, brown, and queer perspectives helps to fill a Grand Canyon-sized chasm in publishing. Reviewer Rachel Jagareski covered the book in Foreword‘s Jan/Feb issue and then found time to engage with Darker Wilderness’ editor, Erin Sharkey, for the following interview.

The writers in this collection greatly expand the definition of nature writing. As your introduction points out, this genre has been dominated by white, male, cisgender perspectives. I so enjoyed Alexis Pauline Gumbs’s tribute to the late Audre Lorde as a “nature poet” whose immersion in real and imagined green spaces both informed her writing and activism, but also nourished her mental and physical health. Are there other writers (aside from those in A Darker Wilderness) not typically associated with this genre whom you would add to the traditional nature writing pantheon?

Oh, so many writers. For me, the best poetry is sensual and evocative. Often, that means poetry that contains natural elements and nature themes because they are inherently sensory. I think of Lucille Clifton; so many of her poems use simple natural objects: the waters, wind, ribs, clay, claws, melt, vapor, lips, nose, and stone to evoke themes of loss, belonging, fatigue, pride, and love. Read any Toni Morrison novel for its nature themes. That will blow your mind. I think of Earthseed, the fledgling faith system in Octavia E. Butler’s The Parable of the Sower, which features many themes of conservation, of change, foraging for seeds, of reading nature’s signs, and reading the stars for direction.

One of the reasons Black writers have been left out of the nature writing canon is that contemporary Americans view nature as separate from us, as something we need to seek out outside of ourselves. Nature needs to be conquered. It needs to be owned and categorized, and ordered. We can not ignore the colonial history of the genre of nature writing because the exclusion of Black folks has had consequences, as has the ways other people of color’s relationship to nature has been relegated to some innate primitive connection. Think about the ways Jim Crow laws kept Black people out of swimming pools many decades ago and their ties to higher rates of drowning for Black people. Or Sundowner laws, which kept Black folks outside town limits after dark, have inevitably contributed to a lack of land ownership by Black people in rural communities. It was not that long ago that that kind of stratification was a rule of thumb for organizing bookstores as well, relegating Black authors to the Black books shelf.

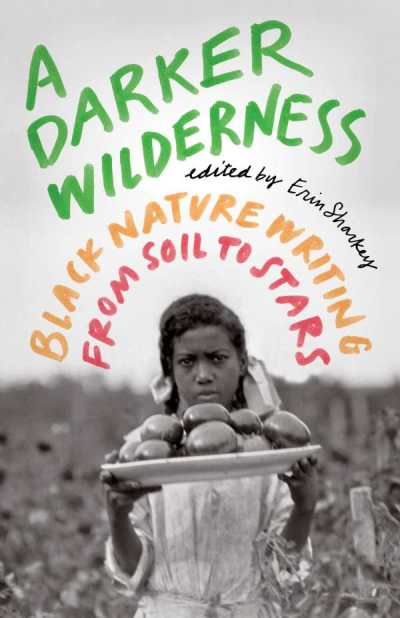

How did you select the writers for this anthology? And what was the inspiration to use the touchstone photos of items from Black history and memory to introduce each essay?

The best part of this project was working with many writers I love and admire. I have a sweet spot for essays written by poets. The ways poets bring the lyric into longer forms excites me. katie robinson and Michael Kleber-Diggs are two of my favorite poets, and both had existing writing I had read in the workshop stage that I believed could be expanded to make for a gorgeous essay. Ronald Greer shared an early and much shorter draft of his essay at a reading with Minnesota Prison Writing Workshop, and I asked him to expand on its themes. I met Glynn Pogue in a travel writing workshop with Faith Adele at VONA, and I was so impressed with her voice on the page and her approach to writing about her experiences overseas. I wondered what she would do with the subject of travel and nature in the US, given her experience with her mother’s inns in the Northeast. When I asked Alexis Pauline Gumbs to write something for the collection, she seemed surprised that I classified her as a nature writer despite being in a project at the moment meditating on marine mammals.

I asked Carolyn Finney and Lauret Savoy to be a part of the collection because I wanted this book to be a continuation of a conversation they started with their books: Black Faces, White Spaces, and The Color of Nature: Culture, Identity, and the Natural World, which Savoy edited with Alison H. Deming.

My intention in including archival objects to accompany each of the essays was to emphasize the long-standing connection of Black folks to nature. Black people have been relating to nature and its care since the origins of this nation. When I reached out to each of the writers I hoped would be in the collection, I sent them some objects to consider. It was fun to look at the archive with each writer in mind, thinking of the topics they write about and the regions to which they are connected. Some writers settled on their objects quickly, while others researched on their own to find an artifact that fit their writing best. Ultimately, some artifacts came from institutional collections, and others from personal and family collections.

The idea that many Black Americans associate natural and rural areas with danger and multigenerational trauma of enslavement, sharecropping, and lynching will be eye-opening for some readers. Have you had any feedback about the book from environmental or conservation groups? What are some ways these groups and parks could become more inclusive and allow for “true relaxation” for people of color, to borrow a phrase from contributor Glynn Pogue?

I have received a few messages of excitement about A Darker Wilderness from environmental justice and conservation groups looking to deepen their commitment to racial justice and to connect with more people as we face the challenges of climate change. I think this book is joining the conversation at a great time. I am eager to be a part of more of these efforts in the future.

While writing this book, my own relationship with rural areas has deepened. Two years ago, my wife, I, and a small group of friends took over the stewardship of thirty six acres of land in central MN. The Fields at Rootsprings is a retreat and respite place centering BIPOC and LGBTQ folks, and we have hosted guests with a wide range of comfortability in rural spaces. Minnesotans have long celebrated cabin culture and going “up north,” and the positive impacts of that kind of rejuvenation have not been accessible to many communities of color here. Our guests sometimes remark that they wish the allies in rural spaces were more vocal and identifiable. The hour-and-a-half drive to Rootsprings from the Twin Cities is marked by messages that can be read as threats. During the 2020 reelection campaign of Donald Trump, several properties along the route donned hand-painted signs threatening Democrats and other opponents of his candidacy.

It is important to remember that cities have also proven unsafe for Black bodies. Some retreat guests have needed respite from the proximity to police and policing in the Minneapolis/St. Paul area after the uprisings that occurred in response to the murder of George Floyd.

The photos that introduce each essay gain so many layers of meaning from the text. Ama Codjoe’s “An Aspect of Memory” completely shifts the image of a young woman seeming to enjoy rain on her face to someone venting powerful emotions while confronting a mob hostile to her civil rights group’s protests. This shifting understanding of the photos is a commonality among the essays. Would you elaborate on this?

The photo included with “An Aspect of Memory” was previously unpublished; it was a part of a group of unused images taken for the Southern Courier in July of 1965 for an article titled “Gas Scatters Demonstrators in Greensboro.” One gift of the archive is the possibility to access the images of events we have a limited view of because of how they were originally reported. Ama’s lingering look at this photograph invites us to really see it as well—to see the shoes in her hands, her head back and her neck open to the viewer from this distance in time allows for the image to mean something more. Time is an important tool utilized by the writers in this collection. They braid together apparently disparate happenings: a protest, a rainstorm, a church bombing that killed four children, the writer’s own mother’s childhood, and the writer’s own. The photo featured alongside each essay is a chance for a long look. And in that looking, for the reader to see a new possibility.

Not all the images have been under public view before. Carolyn Finney and Michael Kleber-Diggs shared objects from their family’s collections. I learned in the curation of this collection that many of the items on display at the National Museum of African American History & Culture in Washington, DC, weren’t on display before its opening. The fact that these items were in private collections may be because of a lack of interest from institutions to collect objects of significance to Black history and memory or from a lack of trust in those same institutions by Black folks who have experienced discrimination and systemic racism perpetuated by them.

I hope readers will also consider the one essay in the collection missing an accompanying image. Readers will find a grey box in place of an archival object next to writing from Ronald Greer II. This exclusion is a placeholder to illustrate the ways inequities deprive some communities of recording and safekeeping of the artifact which hold historical significance but also the traumas of the carceral system (which were further exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic). Ronald is currently incarcerated, which blocked access to archival research opportunities and the safekeeping of personal mementos.

Lauret Savoy’s examination of disrespectful geographic names unpacks a lot about colonialism, racism, and exploitation of the environment. Why do you think there is so much visceral opposition to renaming offensive place names?

That’s a good question, and I suspect there are several answers. Maybe the opposition has to do with fear of being erased or having one’s own version of history written over. Sometimes I think it is about not wanting to be inconvenienced in order to learn to pronounce a word in an unfamiliar language. Maybe it is about the hope that one might be remembered despite one’s mistakes or misgivings.

You know the old saying—history belongs to the victor. Naming in the US has followed that adage, for the most part, while sometimes appropriating racist misunderstandings and ignorance. Names signal a desire to be connected to power and control or a fantasy of a tradition. Namesakes tell tales about who we hope to be. And being de-centered, and taking another place, can feel like something is being stolen from you.

To engage in a renaming, one must confront the dominant narrative the previous name holds up. One must admit that place names can be harmful or exclusionary to move on to a new name. It requires that you acknowledge that the men who named the place were possibly the villains in the story of a place rather than its rescuer, which shakes the foundations of the way many Americans think of themselves and their ancestors. It requires that they admit they’ve been duped by an incomplete understanding of history and have been complicit in the oppression of others.

So many aspects of the “Black experience with all things green” were explored in this collection and thoughtful questions raised about what constitutes the natural world and our connections to it. I’m hoping there will be A Darker Wilderness: Volume Two! Any plans for a second collection? What other writing projects are you working on?

Ahhh, no plans yet, but don’t count a sequel out. I have been dreaming about furthering the conversations started in the collection, though. I think a podcast to explore the book’s themes further would be great. I’d love to invite other thinkers to ponder their relationship with nature. So, if any podcast producers are interested in helping make that happen, please reach out.

Regarding other writing, I have been writing for the stage lately and continuing to think about the role of nature in urban places. And I have started to write about my father, Curtis Sharkey, who died in November of 2020 of COVID-19.

Rachel Jagareski